Correction: When this post was first published, line labels in the panel showing Tier 1 capital ratios were reversed; the labels have been corrected. (November 13, 10:40 a.m.)

Over the past two decades, the growth of shadow banking has transformed the way the U.S. banking system funds corporations. In this post, we describe how this growth has affected both the term loan and credit line businesses, and how the changes have resulted in a reduction in the liquidity insurance provided to firms.

The Syndicated Loan Market before and after the Mid-1990s

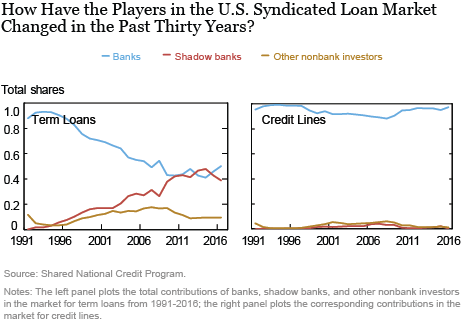

The chart below shows the contributions of banks, shadow banks, and “other nonbank investors” to the financing of syndicated loans taken out by U.S. corporations over the past three decades. Shadow banks include collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), loan funds, pension funds, and hedge funds, while “other nonbank investors” include insurance companies and finance companies. A syndicated loan is financing offered by a group of lenders—referred to as the loan syndicate—who work together under the direction of the lead arranger to provide funds for a borrower.

Banks funded about 90 percent of outstanding term loans in the early 1990s, with the remaining 10 percent funded by nonbank institutional investors, as shown in the left panel of the chart. However, starting in the mid-nineties, the portion of term loans funded by banks began to decline steadily, leveling off at less than half by 2010. The exit of banks was entirely compensated by the growth of shadow banks. As a result, by 2010 shadow banks were as important as banks, with each responsible for funding 45 percent of outstanding term loans. The remaining 10 percent of loans were funded by “other nonbank investors,” which is unchanged since 1990.

In contrast to that of term loans, the funding structure of credit lines did not change over the past three decades, as shown in the right panel of the chart. Throughout this period, banks preserved their exclusive role in funding nearly all of the credit lines granted to corporations. In a term loan, the borrower accesses the entirety of the funding at the time of the loan origination. In contrast, in a credit line, borrowers earn the right to draw down their funds at their will. This uncertainty poses liquidity risk to providers of credit lines and explains why banks dominate this business. Their deposit funding base gives them a wedge to deal with that liquidity risk.

Shadow Banks’ Indirect Effect on Credit Lines

The absence of shadow banks from the credit line business, however, does not mean they had no effect on credit lines. As we document in this paper, the arrival of shadow banks in the term loan business had a negative impact on the liquidity insurance that credit lines provide to corporations.

Firms usually take out deals that comprise both term loans and credit lines. Historically, the set of banks that funded the term loan would also fund the credit line. With the growing presence of shadow banks in the term loan business, some banks, in particular the financially safer ones, exited term loans and in the process also exited the credit line. They may have exited term loans because of the additional competition from shadow banks, or because of the changes introduced in term loans to attract shadow banks. (Specifically, traditional term loans with linear amortization schedules were gradually replaced with “bullet loans” that amortize only at maturity. Bullet loans are more attractive to CLOs and funds because they do not require the lender to manage the stream of cash flow payments from amortization. However, bullet amortization makes loans riskier than traditional term loans and thus not as attractive to banks with lower risk appetite.)

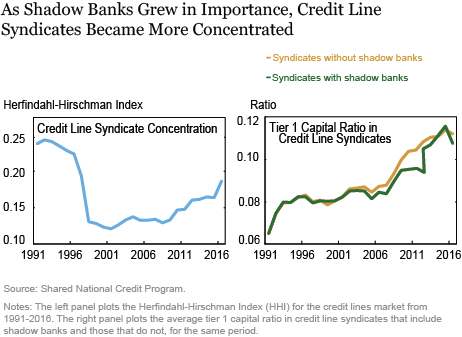

After several years of decline in the concentration of credit line syndicates, since the late 1990s this trend has reversed and concentration has been increasing in parallel with the growth of shadow banks in the term loan business, as shown in the left panel of the chart below. The right panel, which plots the average tier 1 capital ratio in credit line syndicates, shows that credit line syndicates in deals with shadow banks have, on average, lower capital ratios compared to syndicates of credit lines in deals without shadow banks. Here, too, the difference emerges in the period of rapid growth of shadow banks in the term loan business.

These changes in credit line syndicates are important because both the concentration and risk profile of syndicates are critical to the value of a credit line. Credit lines will meet borrowers’ expectations solely to the extent that syndicate members are able to deliver on their credit commitments, because each syndicate member is only formally responsible for its share of the loan investment. In other words, when a syndicate member is unable to meet its loan commitment, the funds available to the borrower are reduced, unless another syndicate member steps in to fill the void left by the former member. Therefore, the more concentrated a credit line syndicate is and/or the riskier are its member banks, the lower the liquidity insurance the syndicate provides to borrowers.

Conclusion

Starting in the mid-nineties, shadow banks began to increase their presence in the term loan business, and by 2010 they were as important to that business as banks, with each being responsible for funding 45 percent of outstanding term loans taken out by U.S. corporations. Throughout this period, shadow banks remained virtually absent from the credit line business. However, their growing presence in the term loan business triggered the exit of some banks, in particular the financially safer ones, from both term loans and the credit lines in the deals containing those term loans. As a result, credit line syndicates became more concentrated and made up of financially riskier banks, thereby reducing the liquidity insurance they offer corporations.

Teodora Paligorova is a principal economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Teodora Paligorova and João A.C. Santos, “The Side Effects of Shadow Banking on Liquidity Provision,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, November 13, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/10/the-side-effects-of-shadow-banking-on-liquidity-provision.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

“Throughout this period, banks preserved their exclusive role in funding nearly all of the credit lines granted to corporations.” In the 1990s, the SEC amended Rule 2a-7 and thereby prevented non-banks from issuing pass through securities directly to money market funds. Does granting banks a monopoly on short-term funding really enhance liquidity, as well as safety and soundness?