Leverage limits as a form of capital regulation have a well-known, potential bug: If banks can’t lever returns as desired, they can boost returns on equity by shifting toward riskier, higher yielding assets. That reach for yield is the leverage rule “arbitrage.” But would banks do that? In a previous post, we discussed evidence from our working paper that banks did do just that in response to the new leverage rule that took effect in 2018. This post discusses new findings in our revised paper on when and how banks arbitraged.

When They Arbitraged

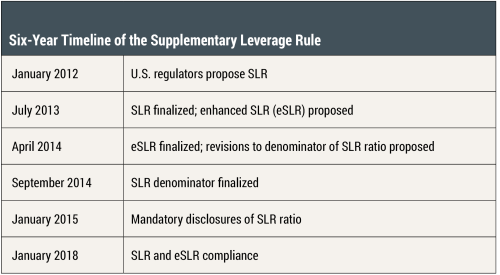

The new leverage rule, like other post-crisis reforms, had a long gestation period:

U.S. regulators first proposed the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) rule in January 2012. The motivation for the rule was to have a simple, unweighted capital requirement as backup in case the risk-weighted requirement did not capture true asset risk at the very large banks using internal, model-based risk estimates. Several years of refinement followed, particularly concerning which assets would count in the denominator of the SLR (“total leverage exposure”). Banks argued for excluding certain “safe” assets, which would tend to make the leverage ratio less binding. The denominator was finalized in September 2014 and the leverage rule wound up as the more binding requirement for most covered banks. Banks were required to disclose their SLR to investors in 2015, but had until January 2018, six years to the month after the rule was first proposed, to comply—in other words, to bring their leverage capital ratios to the required minimum.

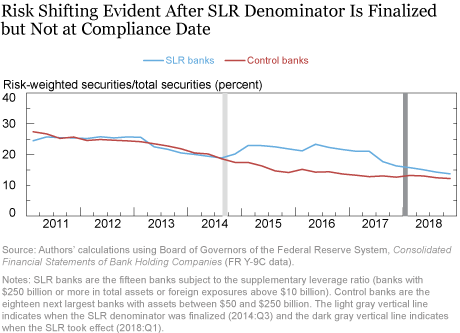

If banks intended to arbitrage the new rule by shifting toward riskier assets, when along that time line would one expect them to do so? Our original paper focused on the third quarter of 2014, when the SLR denominator was finalized, on the grounds that only then did banks know how binding the rule would be. While we found evidence of risk shifting starting then, our data ended before the compliance date in 2018. Did we miss part of the story?

Evidently not. We extend the sample in our revised paper but find no additional risk shifting after the compliance date. To illustrate, the chart below plots the mean ratio of risk-weighted securities to total securities at the fifteen banks covered by the SLR and a control group comprising the eighteen next largest banks (with assets between $50 and $250 billion). The control banks are similarly regulated, save for the new leverage rule. The SLR banks increased their risk-weighted securities ratio—indicating riskier holdings—just as the SLR denominator was finalized in 2014 (the light gray vertical line), but there was no additional risk shifting when it took effect in 2018 (the dark gray vertical line). While it might be surprising that banks did not postpone any shift until absolutely necessary, we show that among SLR banks, those most constrained by the rule began increasing their leverage ratios around the disclosure date in 2015. The timing of this “forced” deleveraging, rather than the official compliance date, may have determined when to reach for yield. More generally, this finding illustrates the perils of identifying regulatory effects when the regulations under study have such long gestation periods and ambiguous “treatment” dates; had we naively compared before and after the compliance date, we might have rejected the arbitrage hypothesis.

How They Arbitraged

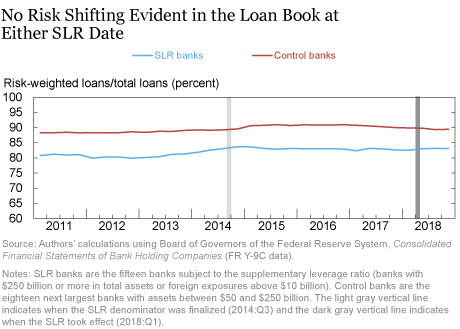

While we find evidence of reach for yield via securities, we find no evidence of a shift toward riskier loans (see chart below). The ratio of risk‑weighted loans to total loans was essentially flat and parallel for SLR banks and control banks. That’s potentially surprising since loans are banks’ signature assets. While it might be that the risk shifting is simply not detectable in risk-weighted loans, we look at alternative credit risk measures (provisions and nonperforming loans) in our revised paper and find no evidence of a differential change in either. While evidence may yet be found, we conclude that effecting a discrete increase in risk might be cheaper and more predictable via the securities books than by forging new loan relationships.

Takeaways

The main takeaway in our revised paper is unchanged: Banks can be expected to arbitrage simple leverage rules by shifting toward riskier, higher yielding assets. Our revised paper shows that arbitrage was effected well before the compliance date for the new leverage rule, and not in the loan book, where one might most have expected it.

Related Reading

Choi, D. B., Holcomb, M. R., and Morgan, D. P. “Bank Leverage Limits and Regulatory Arbitrage: Old Question, New Evidence.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 856, revised December 2019.

Choi, D. B., Holcomb, M. R., and Morgan, D. P. “Leverage Rule Arbitrage.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 12, 2018.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Dong Beom Choi is an assistant professor of finance at Seoul National University. He previously was an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael R. Holcomb is a Ph.D. student at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He previously was a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Donald P. Morgan, Dong Beom Choi, and Michael R. Holcomb, “Leverage Ratio Arbitrage All Over Again,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 30, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/06/leverage-ratio-arbitrage-all-over-again.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

All these posts about financial regulation just make it seem like the only good solution is nationalizing the financial sector. Not sure if that’s the intended outcome but it seems like free markets with regulation work abysmally based on the research posted here.