Benjamin H. Mandel, Donald P. Morgan, and Chenyang Wei

As Nicola Cetorelli observes in his introductory post, securitization is a key element of the evolution from banking to shadow banking. Recognizing that raises the central question in this series: Does the rise of securitization (and shadow banking) signal the decline of traditional banking? Not necessarily, because banks can play a variety of background (or foreground) roles in the securitization process. In our published contribution to the series, we look at the role of banks in providing credit enhancements. Credit enhancements are protection in the form of financial support against losses on securitized assets in adverse circumstances. They’re the “magic elixir” that enables bankers to convert pools of possibly high-risk loans or mortgages into highly rated securities. This post highlights some findings from our article. One key finding: Banks are not being eclipsed by insurance companies (which are part of the shadow banking system) in the provision of credit enhancements.

What We Talk about When We Talk about Bank Credit Enhancements

Everything we know about bank-provided credit enhancements we’ve learned from studying bank holding companies’ (BHCs) FR Y9-C forms (their regulatory reports). Between 2001:Q2, when BHCs were first required to disclose securitization activity, and 2009:Q4, when they were required to bring securitized assets back on their balance sheets, banks reported dollar amounts on three types of enhancement. The first was credit-enhancing, interest-only strips and excess spread accounts. Excess spread is the monthly revenue remaining on a securitization after all payments to investors, servicing fees, and charge-offs. It represents the first line of defense against losses to investors in a securitization, as the excess spread account must be exhausted before even the most subordinated investors incur losses. The second enhancement, subordinated securities and other residual interest, is a standard form credit enhancement. By holding a subordinated or junior claim (or tranche), the bank that securitized the assets is in the position of first-loss bearer, thereby providing protection to more senior claimants. The third enhancement is actually a very traditional banking product: standby letters of credit (SLCs). An SLC obligates the bank to provide funding to a securitization structure to ensure investors of timely payments on the issued securities, for example, by smoothing timing differences in the receipt of interest and principal payments, or to ensure investors of payments in the event of market disruptions. Banks also provide enhancements in the form of representations and warranties that obligate them to take back a loan or mortgage if it defaults early in its life, but we don’t have data on those enhancements.

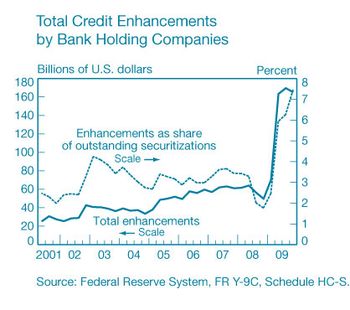

So how much in enhancements did BHCs provide over the window for which we have data? As the chart below shows, total enhancements grew over the period from about $25 billion in 2001:Q2 to about $60 billion in 2008:Q2. There was a spike in 2008:Q4, which reflected a surge in enhancements on credit card securitizations at just two banks (see our article for more detail on those events). Total enhancements scaled by total securitizations by BHCs averaged about 3 percent until the surge in 2008:Q4.

Banks versus Insurance Companies

Our article also investigates whether BHCs were being eclipsed by insurance companies (part of the shadow banking system) in the provision of enhancements. Insurance companies provide credit enhancements in the form of guaranties and credit default swaps (insurance against default). As there is no central source of data on enhancements provided by insurance companies, we turn to their annual reports (form 10-K) for data. Starting with the nineteen publicly traded insurance companies, we determine that only six or seven (depending on the year) provided guaranties for asset-backed securities. These included firms such as Ambac, MBIA, and Radian. While the companies usually provided a reasonable breakdown of guaranty coverage by type—such as residential or consumer loans—the classifications were not uniform across companies. Thus, for each company we summed guaranties across categories and then summed across companies to obtain the aggregate level of guaranties by publicly traded insurance companies in a given year.

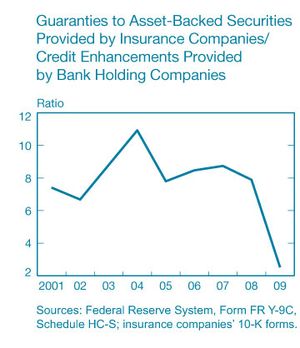

The chart below plots the ratio of enhancements provided by insurance companies to enhancements provided by BHCs. The first thing to note is that enhancements by insurance companies outnumber enhancements by BHCs by roughly eight to one, so they’re the dominant source of enhancements. More to our point, however, is that the ratio is essentially flat for most of the period shown, so BHCs have not been losing share to insurance companies (the drop in the ratio starting in 2008:Q4 is mostly a distraction; it reflects the surge in enhancements at two BHCs discussed above). In fact, insurers are forthright about the competition they face from banks in the enhancement business:

“Our financial guaranty insurance and reinsurance businesses also compete with other forms of credit enhancement, including letters of credit, guaranties and credit default swaps provided, in most cases, by banks, derivative products companies, and other financial institutions or governmental agencies, some of which have greater financial resources than we do, may not be facing the same market perceptions regarding their stability that we are facing and/or have been assigned the highest credit ratings awarded by one or more of the major rating agencies” (Radian Groups 2007 10-K, p. 46).

So on the overall question of whether banks are losing market share to a shadow bank (in this case, insurance companies) in the business of providing enhancements, our answer is a simple “no.”

Enhancements: Buffer or Signal?

Our article also investigates in more detail precisely what role enhancements play in the securitization process. The typical view is that enhancements serve as a buffer against the risk of default on the underlying collateral—they’re a form of meta-collateral. This view follows from the way the level of enhancements is determined in the credit rating process; the rating agencies estimate a loss function on the underlying collateral and the higher the estimated losses, the higher the level of enhancement necessary to receive a given rating. Those mechanics suggest a negative relationship between the level of enhancements on a deal and the performance of collateral; deals with riskier collateral will require higher enhancements and, ex post, if the estimated losses are correct, the collateral on those deals with more enhancements will have a higher default rate. Note that in this scenario, enhancements serve as a buffer against observable risk (as embodied in the estimated loss function); if the collateral looks riskier to an outside party (the raters), more enhancements are necessary (to be top rated).

In our paper, we were interested in the possibility that banks might use enhancements to signal the unobservable quality of the assets they’re securitizing. It’s generally acknowledged that securitization is plagued by some degree of asymmetric information, that is, the bankers know more about the quality of the collateral backing a securitization deal than do investors in the deal. According to the signaling story, bankers can signal the quality of the assets they’re securitizing by their willingness to keep “skin in the game” (which is what an enhancement does—it exposes the bank to losses). Note that the signaling story implies a positive relationship between the level of enhancements and the performance of the collateral (since the enhancements are signaling quality), just the opposite of the buffer story above.

Alas, our statistical analysis is not kind to the signaling story. We look at the relationship between nonperformance (delinquent or charged-off) of securitized assets and the associated level of enhancements (scaled by the amount of securitization) for seven categories of credit. We never observe a negative relationship between nonperformance and enhancements, as the signaling story implies. By contrast, we observe a positive relationship between nonperformance and enhancements for four of the seven loan categories considered. We conclude that the more widely held buffer view seems to fit the data better. Of course, enhancements could serve as both a buffer against observable risk and a signal of unobservable quality, with the former role dominating. Teasing that out is the topic for another post.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Benjamin H. Mandel is a former assistant economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Chenyang Wei is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics