Jennie Bai, Christian Cabanilla, and Menno Middeldorp

During the recent financial crisis, the absence of an orderly resolution regime forced governments of several countries to provide extraordinary support to a number of systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) that were considered “too-big-to-fail.” Since then, new laws such as the Dodd-Frank Act have established a framework to resolve SIFIs without the need for government “bail-outs.” These types of laws have important implications for senior bondholders of SIFIs, as the use of the new regimes would likely expose creditors to losses. Given this change, this post investigates whether markets are adjusting their perceptions of the risk associated with global SIFIs. We find that in response to shifting regulatory regimes, investors are beginning to price in a higher risk of default on senior bonds issued by the institutions.

International Approaches to Tackling Too-Big-to-Fail

The general intent of laws to resolve SIFIs is to avoid putting taxpayers’ money at risk through support measures such as direct lending or capital injections. Under a number of the new global resolution regimes, a financial firm may be liquidated through an orderly unwind procedure or recapitalized through the “bailing in”

of debtholders—a process that involves either writing down senior claims or converting them to equity. In any case, a senior debtholder’s risk of default is likely to be greater under these scenarios than it is when the SIFI receives government support.

Resolution regimes and progress in implementing them vary across countries. Germany,

the United Kingdom, and the United States have enacted legislation surrounding resolution regimes, while the European Commission has proposed a new framework

for resolution that would apply to all EU

countries.

Furthermore, the Financial

Stability Board, working under the auspices of the

G-20, has agreed on resolution measures that would apply to a list of global

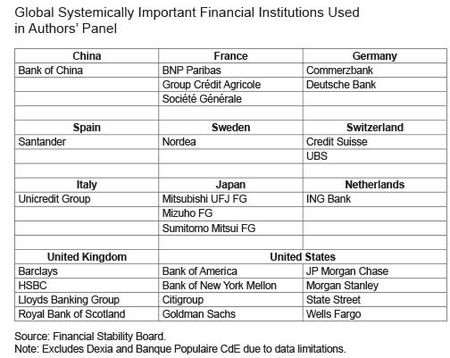

systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs). As G-SIFIs may be the most sensitive to changes in resolution regimes, we focus on them (see example below).

Measuring Market Perceptions of Progress

on Resolution Regimes

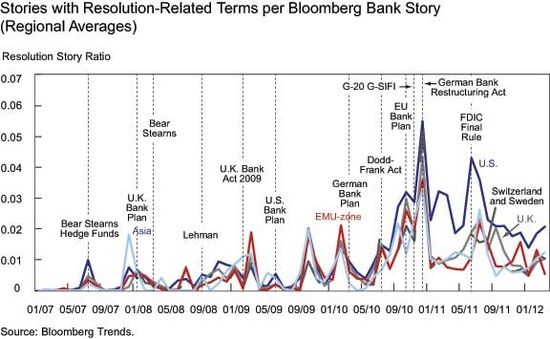

Is progress on resolution regimes affecting market perception of default risk on senior bonds? To answer this question, we could just use the dates of regulatory changes to mark progress on resolution regimes, but it’s highly likely that markets responded to news of pending changes well before actual laws were passed. To capture this reality, we count the number of Bloomberg news articles that mention resolution-related terms specific to individual G-SIFIs and divide it by all the news stories specific to that institution. This gives us a time-series per bank that indicates market expectations associated with regulatory changes. The chart below shows the average news story ratio across banks by region.

Measuring Market-Implied Default Risk

We use Moody’s KMV credit

default swap (CDS) implied probability of default

to gauge changes in the market perception of the risk that senior bondholders

will not be completely repaid. For instance, a resolution regime that would

entail higher expected losses for senior creditors would require higher spread

compensation for bondholders and imply higher probabilities of default. Of

course, we need to control for other drivers of default probability that have

nothing to do with resolution authority. To do so, we use the following control

variables:

- Moody’s KMV equity-implied default probability per bank

- Moody’s KMV index of investment-grade CDS implied-default probabilities per country

- Moody’s KMV sovereign CDS-implied probability of default

- The S&P 500 implied volatility index (VIX)

Equity at a number of G-SIFIs experienced large losses or was heavily diluted around many of the government interventions during the crisis. As equity remains the first to incur losses in an orderly resolution, default probabilities calculated on the basis of equity prices are less likely to be affected by changes in resolution regime, but rather capture a range of risks.

Average CDS spreads of all investment-grade companies are likely to be insensitive to changes in resolution regimes, while capturing country-specific drivers of default risk.

While a shift in a resolution regime reflects a change in the government’s willingness to provide support, it’s also possible that, because of fiscal stress, governments become less able to finance a troubled bank. To capture this, we include sovereign CDS.

Global perception of market risk is generally well reflected in the VIX.

Use of implied default probabilities in the dependent and control variables makes our results in the table below easier to interpret. However, it also means we need to rely on additional assumptions and techniques to translate the market data into default probabilities. To make sure it’s not the methodology that’s driving the results, we conduct a number of robustness checks. We confirm that the implied rates

respond to market prices (which are used as inputs in implied default

probabilities) in the way we’d expect. Furthermore, if we replicate the

regression presented in the next section using those market prices, we get

similar results.

Higher Default Expectations Due to Resolution Regime Changes

We run a panel regression on monthly changes in the above variables from June 2007 to March 2012. We restrict the Bloomberg news ratio to increases in the variable, as we believe that a decline in news stories doesn’t reflect a reduction in the likelihood of a change in resolution regime, but rather the passing of market attention to a specific program. Indeed, declines in this variable are not statistically significant.

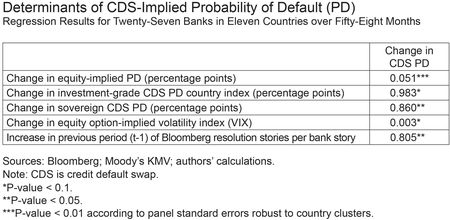

As shown in the table below, the control variables have the expected signs and are statistically significant to varying degrees. Increases in Bloomberg news related to resolution regimes, the main variable of interest, are associated with a higher risk of default implied by CDS and significant at the 5 percent probability level.

Using the results from this regression and the shift in Bloomberg resolution news over our sample, we estimate that the anticipated and actual changes in resolution regime have increased the CDS market’s expectations of default by approximately 20 basis points, which is around a fifth of the average CDS-implied default probability for G-SIFIs in March 2012. While this doesn’t necessarily mean that markets are no longer pricing in any possibility of government support, it does suggest that the new laws have resulted in the CDS market taking into account the view that senior bondholders run a higher risk that they’ll need to share in the costs of bank resolution.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jennie

Bai is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Christian Cabanilla is a senior economic analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Menno

Middeldorp is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics