Kenneth D. Garbade

Note: This post draws on many sources contemporary with the events described, including various Treasury and Federal Reserve publications and news articles from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. These sources are fully documented in the PDF version of the post.

In the second half of 1953, the United States, for the first time, risked exceeding the statutory limit on Treasury debt. How did Congress, the White House, and Treasury officials deal with the looming crisis? As related in this post, they responded by deferring and reducing expenditures, by monetizing “free” gold that remained from the devaluation of the dollar in 1934, and ultimately by raising the debt ceiling.

Treasury Debt and the Debt Ceiling before 1953

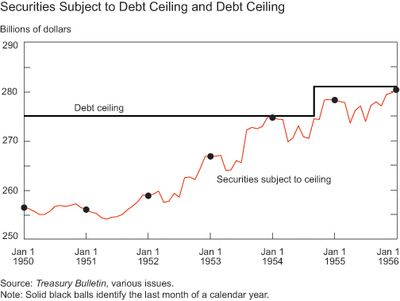

Congress adopted the modern form of the debt ceiling in July 1939: a $45 billion limit on the aggregate outstanding amount of debt issued under the authority of the Second Liberty Loan Act of 1917. (An earlier post in this series discussed the antecedents of the 1939 legislation. A small amount of indebtedness, including $50 million of fifty-year bonds issued in 1911 to finance construction of the Panama Canal, was issued or incurred under other authorities and was never subject to the ceiling.) Congress raised the debt ceiling to a peak of $300 billion during World War II and then lowered it to $275 billion in June 1946. Debt subject to the limit (hereafter, “Treasury debt”) stood at $268 billion in mid-1946, fell to $252 billion in mid‑1948, and thereafter fluctuated between $252 billion and $258 billion until mid-1951.

Beginning in mid-1951, Treasury debt began to rise, primarily because of the costs of the Korean War and other defense appropriations. As shown in the following chart, Treasury debt rose in the fall of each year and declined the following spring, but nevertheless increased from one year-end to the next.

The seasonal pattern of Treasury indebtedness stemmed from a provision in the Revenue Act of 1950 requiring corporations to remit a larger fraction of their income taxes in the first half of the tax year than in the second half. For companies on a calendar-year tax year, 60 percent of the income tax due in 1951 was due in the spring and 40 percent in the fall. The spring fraction increased to 70 percent in 1952, 80 percent in 1953, and 90 percent in 1954. As a result of the front-loading of tax liabilities, the Treasury issued short-term debt in the fall (when tax payments ebbed) to be repaid the following spring (when payments would swell). The progressive increase in the fraction of payments due in the spring, and the complementary decline in the fraction due in the fall, amplified the seasonal pattern from one year to the next.

The First Half of 1953

Corporate tax receipts in the spring of 1953 saw the Treasury comfortably through the first six months of the year, but officials knew that receipts would drop off in the fall. On June 3, Secretary of the Treasury George Humphrey testified before the House Ways and Means Committee that he expected to have to borrow between $9 billion and $12 billion of new money before the end of the year. Treasury debt at the time amounted to $266 billion and officials speculated that Congress might have to raise the debt ceiling.

Reaction to the prospect of an increase in the debt ceiling was swift and sharp. Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia, a prominent conservative, declared that, in order to pressure the new Eisenhower Administration to cut spending and restore a balanced budget, he would do “everything in [his] power” to block an increase. The Wall Street Journal opined on its editorial page that “to impose a limit on the government’s debt and then to change it the moment it begins to squeeze makes of the whole thing a trick for fooling people.” On July 1, the Treasury announced a record peacetime deficit of $9.4 billion for the fiscal year just ended —$3.5 billion more than had been projected six months earlier. Secretary Humphrey noted that “difficulties of this size cannot be cured overnight,” and that “many months” of effort would be required “to get the situation under control.”

To cope with the looming autumnal decline in tax receipts, on July 6 the Treasury offered for sale at par about $5½ billion of eight-month tax anticipation certificates. It received subscriptions for more than $8½ billion of the certificates and ultimately sold $5.9 billion. More would surely be needed, but by the end of July there was only $2.9 billion of headroom remaining below the debt ceiling.

On July 30, one day before Congress planned to adjourn, President Eisenhower asked Congress to approve a $15 billion expansion in the debt limit, to $290 billion. The House of Representatives quickly approved the request (on a vote of 239 to 158) but, despite the testimony of Secretary Humphrey that failure to raise the debt ceiling could lead to “near panic,” the Senate Finance Committee pigeon-holed the initiative. Congress adjourned without taking action, leaving Administration officials to manage as best they could.

Coping with the $275 Billion Debt Ceiling

Reducing cash disbursements was one way for the federal government to avoid the looming crisis. On August 6, President Eisenhower directed all federal agencies to “begin immediately to take every possible step progressively to reduce . . . expenditures.” In early October, the New York Times reported that the Department of Defense had tightened control over contractor progress payments and that it was encouraging contractors to borrow from private-sector banks rather than depend on government financing, a policy that was “said to have drawn protests from business affected by the program.” In November, the Times reported that “the Government [had] established a slow-down on paying for production and construction work being done under Federal contract.”

The Treasury could help ease the crisis by drawing down cash balances that it maintained with commercial banks and with its fiscal agents, the twelve Federal Reserve Banks. Officials were, however, reluctant to let balances fall too far at a time when they might not have room to borrow more in an emergency. It was reported that Secretary Humphrey wanted to maintain a $6 billion “cushion” against the risk that revenues and expenditure reductions might come in below expectations during the fall. Senator Byrd thought the Treasury could get by with a $4 billion cushion.

A third way of coping with the crisis was for the Treasury to repurchase outstanding debt, thereby increasing the headroom available for issuing new debt. The problem, of course, was how to pay for the purchases.

Monetizing Gold

The solution to the debt ceiling crisis came from the third option and involved a stock of almost $1 billion of “free” gold—that is, gold coin and bullion in Treasury vaults on which gold certificates had not yet been issued. The free gold was what remained of $2 billion that had been allocated (by the Gold Reserve Act of January 30, 1934) to the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) out of the $2.8 billion derived from the revaluation of 194 million fine ounces of Treasury gold (from $20.67 per ounce to $35 per ounce) in 1934. Of the $2 billion, $200 million had been used as ESF working capital and the other $1.8 billion was carried on the books of the Treasury as gold held for the ESF. The Bretton Woods Agreements Act o

f July 31, 1945, directed the Secretary of the Treasury to transfer to the Department’s general fund the $1.8 billion of gold to pay part of the $2.75 billion capital subscription of the United States to the International Monetary Fund due on February 26, 1947. As of June 30, 1953, $984 million of free gold remained in the general fund.

On October 28, the Treasury came to market with its second cash offering of the fiscal year, about $2 billion of seven-year, ten-month bonds offered at par for settlement on November 9. The Treasury received subscriptions for more than $12½ billion of the bonds. Subscriptions for up to $10 thousand were allotted in full; larger subscriptions from mutual savings banks, insurance companies, pension and retirement funds, and state and local governments were allotted 24 percent; and larger subscriptions from all others were allotted 16 percent. In all, the Treasury committed to deliver $2.238 billion of bonds. Treasury debt amounted to $272.875 billion at the end of October and thus would be about $114 million over the $275 billion ceiling when the new bonds were issued on November 9. The New York Times quoted a Treasury Department spokesman as saying that “the department would now have to take some sort of action to prevent the public debt from going over the legal top.”

On Monday, November 9, the Treasury announced that it had monetized $500 million of its free gold by issuing gold certificates against the gold and depositing the certificates with the Federal Reserve, and that it had used the resulting credits to repurchase directly from the System Open Market Account $500 million of Treasury notes maturing in December. The action did not affect monetary policy —it merely replaced one asset (the Treasury notes) with another (the gold certificates) on the Fed’s books.

The headroom available for additional Treasury debt issuance expanded gradually from $293 million at the end of November to $700 million at the end of February 1954, and then jumped to $5.2 billion at the end of March as March tax receipts funded a paydown of $4.5 billion of marketable debt. After that, the Treasury had clear sailing—at least until the fall of 1954, when it would face a replay of the second half of 1953.

Raising the Debt Ceiling

In the spring of 1954, Treasury officials launched a renewed effort to raise the debt ceiling. The Wall Street Journal reported that officials expected Treasury debt to reach $270 billion by the end of June, before any of $10 billion of needed autumnal debt had been issued, and that they “might be willing to accept ‘alternatives’ to a straight dollar rise in the debt limit.” The Journal noted several such alternatives, including placing tax anticipation securities outside the debt limit (to facilitate seasonal borrowings), placing special issues of Treasury debt (such as those issued to the Social Security trust fund) outside the limit, and increasing the limit temporarily (to give Congress and the Treasury more, though explicitly limited, time to get their fiscal affairs in order).

In early August, Secretary Humphrey notified the Senate Finance Committee that he would settle for a $10 billion increase in the debt ceiling, divided between a $5 billion permanent increase and a $5 billion temporary increase. Senator Byrd offered a temporary $5 billion increase and the parties compromised at a $6 billion increase, to expire on July 1, 1955. The compromise passed into law on August 28, 1954. Treasury indebtedness expanded to $278.357 billion at the end of November, so the ceiling would have been exceeded without the increase.

The August 1954 resolution of the debt ceiling crisis was not expected to be a permanent fix. The chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Eugene Millikin, predicted that “further review” of the matter would be necessary in 1955. Senator Walter George of Georgia cautioned against optimism that the rise would, in fact, be temporary.

An Endnote: How Fannie Mae Came to Issue Debt Directly to Investors

At about the time that Congress was debating the increase in the debt ceiling, it was also putting the finishing touches on the Housing Act of August 2, 1954. Among other things, the act authorized the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, or “Fannie Mae”) to issue debt to private investors—Fannie Mae had previously funded its operations by borrowing directly from the Treasury—and provided that Fannie Mae “shall insert appropriate language in all of its obligations issued under this subsection clearly indicating that such obligations . . . are not guaranteed by the United States.” The Wall Street Journal observed that “the purpose of issuing non-guaranteed securities, of course, is to avoid pushing the Treasury’s debt toward the ceiling.” The Journal further reported, at the time of the first public offering of Fannie Mae debt, that the president of Fannie Mae had “received written assurance from the Treasury ‘that it would lend to F.N.M.A. any amount that may be necessary to meet its obligations.’”

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Kenneth D. Garbade is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics