Mary Amiti and David E. Weinstein*

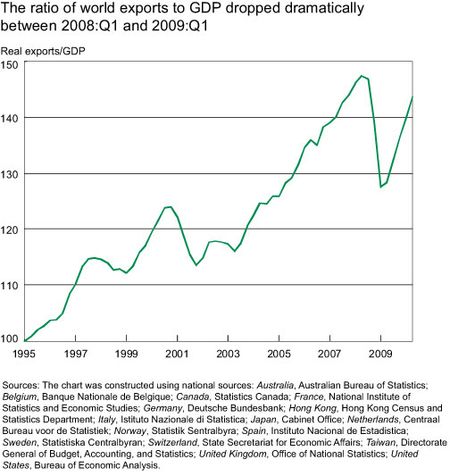

The financial crisis of 2008-09 brought about one of the largest collapses in world trade since the end of World War II. Between the first quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, the value of real global GDP fell 4.6 percent while exports plummeted 17 percent, as can be seen in the chart below. The dramatic decline in world trade—a loss of $761 billion in nominal exports—came through two channels: decreased demand for imports and supply effects, most likely arising from financial constraints. In this post, we look at evidence that supply effects, including curtailed funding for export-related activities, played a key role in the trade collapse—and thus in the transmission of the financial crisis from Wall Street to “Main Street,” here and abroad.

Understanding what caused the decline in world trade is important for understanding how business cycles are transmitted internationally. It is easiest to first think about how the crisis caused changes in demand that affected imports. Higher unemployment and reductions in household wealth likely led many consumers to cut back on spending, causing the U.S. demand for imports to fall as well. Moreover, many traded goods consist of durable goods, such as automobiles, whose purchase can be delayed in economic downturns. As a result, trade tends to be two to three times more volatile than GDP.

However, strains on financial institutions during the crisis also played an important role in the decline in trade. These are considered supply effects. First, many shocks that may superficially appear as demand shocks may actually have been due to lack of credit. For example, ailing financial institutions may have been forced to cut back on lending. As a consequence, consumers and firms that were denied credit for the purchase of consumer durables and investment goods may have delayed or forgone purchases, resulting in lower demand for imports.

Trade finance provides another channel through which supply shocks can reduce exports. Exports are arguably more sensitive to financial shocks because of the higher default risk and higher working capital requirements associated with international trade. Exporters often have a much harder time evaluating default risk and collecting payments than firms that sell domestically. Moreover, the fact that many exports travel by sea places additional working capital burdens on international transactions because trading partners need financing to cover the costs of goods in transit. As a result, exporters often work with banks and other financial institutions to obtain trade finance and export credit insurance.

We have two kinds of evidence on the importance of supply effects. First, in Amiti and Weinstein (2011), we use unique matched firm-bank data to examine the link between finance and exports during the Japanese financial crises of the 1990s as well as the more recent crisis of 2008-09. Japan is also a particularly interesting case study because the collapse of Lehman Brothers had an immediate impact on several Japanese banks. For instance, Aozora and Mizuho were two of Lehman’s five largest unsecured creditors and had a combined exposure of close to $1 billion, according to the 2008 Lehman bankruptcy filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

Our results suggest that banks that become unhealthy during financial crises cut back on loans in general, but cut back even more sharply on trade finance. Moreover, we see that within an industry, firms whose banks became unhealthy cut back on exports much more sharply than they did on domestic sales. This behavior establishes that the severe contractions in short-term trade finance associated with declines in bank health have immediate impacts on real economic activity, like exporting.

In Ahn, Amiti, and Weinstein (2011), we provide some important new evidence that the supply shocks may have been larger for exports than for domestic sales during the financial crisis. The evidence in favor of supply effects driving a large portion of the trade collapse comes from price data. While both supply and demand contractions lead to output downturns, they have different implications for firm pricing decisions. Demand contractions tend to cause prices to fall, whereas supply contractions tend to cause prices to rise.

Applying this logic, we compare export price inflation to producer price inflation for a number of OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. The U.S. data, presented in the chart below, clearly show that the relative price of U.S. exports spiked sharply following the Lehman bankruptcy. In the fourth quarter of 2008, U.S. export prices for manufacturing had risen by almost 8 percent relative to domestic manufacturing prices. This was the largest relative price increase for exports that we observed over the past ten years.

This spike suggests that the relative importance of supply shocks hitting exports was larger than that for domestic sales. We can reject an alternative interpretation of these results—that the spike might be the effect of a dollar depreciation. In fact, the trade-weighted dollar appreciated against other currencies in the fourth quarter of 2008. Moreover, it turns out that the relative price increases depicted in the chart were also present in other countries. European exporters also raised their prices relative to prices of domestic producers, and even Japanese exporters—who saw their export values decline by 50 percent during the crisis—raised their prices relative to their domestic prices.

Our findings underscore the role played by financial crises in understanding the forces that cause downturns in real economic activity. While it is difficult to say exactly how important these supply shocks were for the world as a whole, we now have an important indication. Our results suggest that about one quarter of the decline in Japanese exports may have been due to credit tightening arising from deteriorating bank health. Applying this conclusion more broadly suggests that a key way in which financial crises cause recessions and spread them globally is by rapidly cutting off trade-related finance, which quickly shuts down all types of “Main Street” activities here and abroad, including the making, buying, selling, and transporting of huge volumes of imports and exports.

*David E. Weinstein is the Carl S. Shoup Professor of the Japanese Economy at Columbia University and associate director for research at Columbia’s Center on Japanese Economy and Business.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks for your comment. There are a couple of points we would like to highlight to explain why we don’t think that our results are driven by the “psychology of the market.” First, we find a differential effect on export sales relative to domestic sales. Further, this differential effect exists even after controlling for foreign market shocks, so it would be difficult to explain why the psychology argument would affect exports more than domestic sales. Second, we find that after controlling for demand shocks it is the exports of firms with loans from banks that got into trouble that fell during the crisis periods. This establishes a clear channel of causality from trade finance to exports.

My view is that trade decreased because the psychology of the market changed. Keep in mind that our monetary unit is now a non-thing (psychological) and when mass psychology changes, than decisions (including the import and export of goods) also changes. The old days of a material monetary unit are now history. Today, our ‘dollar’ is created via decisions of our FOMC and our Fed influences the entire marketplace via their psychology and philosophy. Mass psychology also changes when historic events are internalized by participants in the marketplace. The crash of 2008 was such an event, in my opinion. D