Olivier Armantier, Giorgio Topa, Wilbert Van Der Klaauw, and Basit Zafar

Surveys of consumers’ inflation expectations are now a key component of monetary policy. To date, however, little work has been done on 1) whether individual consumers act on their beliefs about future inflation, and 2) whether the inflation expectations elicited by these surveys are actually informative about the respondents’ beliefs. In this post, we report on a new study by Armantier, Bruine de Bruin, Topa, van der Klaauw, and Zafar (2010) that investigates these two issues by comparing consumers’ survey-based inflation expectations with their behavior in a financially incentivized experiment. We find that the decisions of survey respondents are generally consistent with their stated inflation beliefs.

Inflation expectations are at the center of modern macroeconomic models and monetary policy. If agents are forward looking, then beliefs about future inflation should influence present behavior and thereby affect realized inflation. As Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has often noted, managing inflation expectations is a critical first step in controlling inflation. Considerable attention has therefore been devoted to understanding and measuring inflation expectations. In particular, several central banks around the world, including the Federal Reserve, have recently designed inflation expectations surveys of individual consumers. These surveys, however, are useful only if consumers actually act on their inflation beliefs. In addition, one may question the extent to which the expectations elicited through these surveys represent the respondents’ actual beliefs.

For several reasons, surveys may not be informative about the true inflation beliefs of individual consumers. First, the absence of financial incentives may cause respondents to deliberately misreport their beliefs. Second, respondents without prior beliefs about inflation may not make the effort to come up with their best estimate, and thus may not provide thoughtful responses. Third, the wording of the survey questions may not be entirely clear to the respondents, causing the respondents to respond to a question slightly different from the one the survey designer intended.

There are also several reasons to question the hypothesis that agents act on their inflation beliefs. First, some lab experiments have shown that agents do not systematically behave in a way that is consistent with their beliefs. Second, the possible impact of future inflation on some agents may be minor compared with other risks they face (for example, a job loss). As a result, when these agents make decisions, they may decide to ignore future inflation and focus on more salient risks. Finally, one cannot exclude the possibility that some individual consumers are myopic and therefore make decisions without taking into consideration future risks such as inflation.

In our study, we investigated these issues by asking a group of individuals to take part in two activities—a survey of inflation expectations and a financially incentivized experiment. An important feature of the study was that at the time these individuals responded to the survey, they were not aware that they would subsequently participate in an experiment. In the survey, we elicited the respondents’ inflation expectations. In the experiment, we asked the respondents to choose between investments whose final payoffs depended on future inflation. The objective was to compare a respondent’s survey response with his or her choices in the experiment. The survey was fielded to 745 respondents by the RAND Corporation at the end of July 2010.

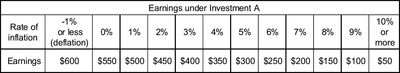

The respondents first had to answer an inflation expectations question of the form “Over the next twelve months, I expect the rate of inflation to be ___percent OR the rate of deflation (the opposite of inflation) to be ___percent.” Then, the respondents took part in an experiment consisting of ten questions. For each question, the respondent was asked to choose between two investments, investment A and investment B. Each investment generated a specific earning that would be paid to the respondent twelve months later. The respondent’s payoff under investment A depended in part on the annual rate of inflation. The possible earnings as a function of inflation were presented in a table like the one below, where the rate of inflation was defined for the respondents as the official U.S. consumer price index over the following twelve months rounded to the nearest percentage point. In each of the ten questions, investment A remained the same. In contrast, the earnings produced by investment B were fixed in each question (that is, they did not vary with inflation), but they changed from one question to the next. More specifically, the earnings of investment B increased (in increments of $50) from $100 in question 1 to $550 in question 10.

It is then easy to show that a rational respondent should switch investments at most once, from investment A to investment B. For instance, consider an expected payoff maximizer with an inflation expectation of 4 percent. This respondent should select investment A for the first five or six questions (in question 6 the respondent is indifferent between the two investments since they both earn $350), and then should switch to investment B for the remaining questions.

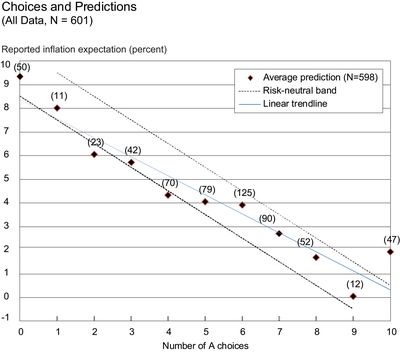

A summary of the main results of the study is provided in the chart below. This chart displays the relationship between a respondent’s reported inflation expectation and the number of times he or she selected investment A before switching to investment B. For instance, we can see that fifty respondents always selected investment B and reported an average expected inflation rate of 9.3 percent. The chart also displays a risk‐neutral band indicating the range of beliefs that would rationalize each switching point under risk neutrality. Points below (above) the risk-neutral band may be rationalized under risk aversion (risk loving).

We also find that most of the diversity in choices in the experiment may be rationalized under expected utility. That is, respondents who behaved in a risk-averse manner in the experiment also reported (in response to a different question in the survey) that they were less willing to take risk when making financial decisions. Finally, the subjects whose behavior was inconsistent with expected utility (for example, they behaved in the experiment as if they were very risk-loving but they reported in the survey that they were very risk-averse) tended to display a very specific characteristic: They scored lower on a scale measuring education, numeracy, and financial literacy.

Our results therefore provide some evidence that surveys of consumers’ inflation expectations are informative in the sense that respondents report beliefs that are generally consistent with the decisions they make in a financially incentivized experiment. In addition, we would suggest that when consumers are presented with an opportunity to act on their inflation beliefs, they tend to do so. Although this does not prove that the decisions made by individual consumers in their daily lives are influenced by the beliefs they hold about future inflation, these results may constitute preliminary evidence in support of this view.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics