Christian Grisse, Thomas Klitgaard, and Ayşegül Şahin

The employment-to-population ratio—the share of adults that are employed—has historically been much higher in the United States than in Europe. However, the gap narrowed dramatically in the last decade and had almost disappeared by the end of 2009. In this post, we show that the narrowing employment gap is due to three factors: declining U.S. employment rates across almost all age-gender groups; more women working in Europe, particularly prime-age and older workers; and rising employment for older European men. We link most of these shifts to the influence of underlying trends (many reflecting changes in European social policies) and to differences in labor market performance during the Great Recession.

Between 1980 and 2000, the employment-to-population ratio was on average about 10 percentage points higher in the United States than in Europe. Part of this difference was attributable to higher labor taxes, higher minimum wages, and better benefits for unemployed and retired workers in Europe. In particular, higher labor taxes discourage people from working and higher minimum wages contribute to joblessness among unskilled and young workers. In addition, more comprehensive unemployment insurance discourages unemployed workers from accepting less desirable jobs, the lower cost of higher education reduces employment among student-age workers, and more generous pension systems encourage workers to retire earlier.

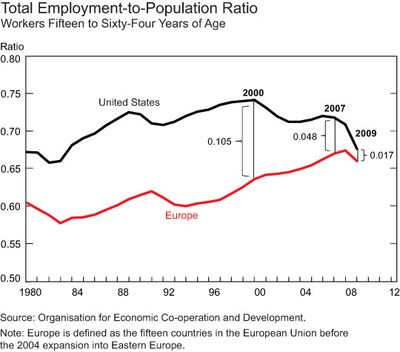

However, as the chart below shows, the gap between the employment-to-population ratio in the United States and Europe (defined here as the fifteen countries in the European Union before the 2004 expansion into Eastern Europe) has declined significantly in recent years, narrowing from 10.5 percentage points of the population in 2000 to 4.8 percentage points in 2007. The gap narrowed further during the global financial crisis and recession and had almost vanished, at 1.7 percentage points, in 2009.

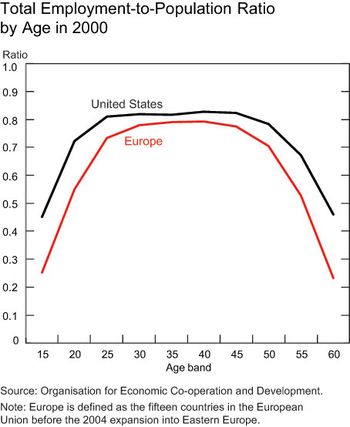

The reason for the narrowing can be gleaned by breaking down the labor market by demographic group. As the charts below show, employment rates by age and gender exhibit inverted U-shapes that illustrate differences in employment rates between the United States and Europe and in the way the rates have changed over the last decade. In 2000, the gap was most pronounced at the tails. Younger and older workers in the United States were much more likely to have a job than their counterparts in Europe. At the same time, the shares of people working in their middle years (ages twenty-five to fifty-five) were quite similar. This picture is consistent with the view that more generous government support in Europe was an important part of the difference in overall employment rates.

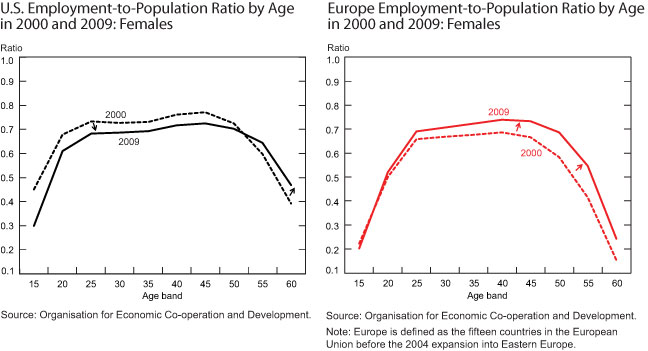

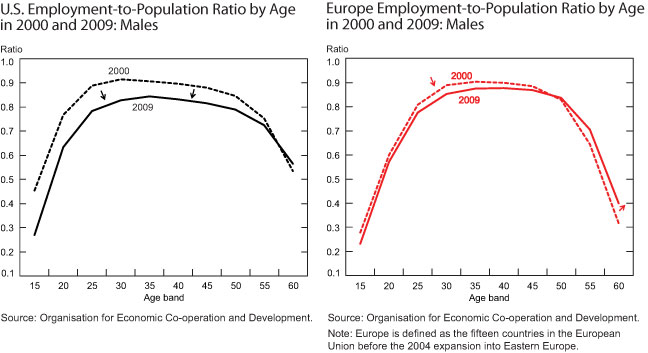

Breaking the charts down by gender shows the same differences in employment rates at each end of the age distribution, but no meaningful differences for prime-age male workers. This finding is consistent with the view that taxes and benefits are more likely to affect those with lower labor force attachment, like younger or older workers. The gap in employment rates for females, though, is wide across all age groups. Comparing changes in employment rates from 2000 to 2009, we see a significant narrowing of the gap between the United States and Europe. U.S. employment growth was weak even over the decade before the recession, which then accentuated the decline in employment rates relative to 2000. Employment rates for male and female workers in the United States decreased for all but the oldest age groups over that period. After increasing for decades, the female labor force participation rate leveled off in 2000 and has fallen in the last decade. The decline is evident even among highly educated women.

Europe had a very different experience: Employment rates for the young and prime-age populations did not change much, while the rate for older workers increased. In particular, the employment rate for prime-age male workers declined less than it did in the United States, while the rate for women increased across demographic groups and especially for older women. Note that the female labor force participation rate increased in Europe, approaching the U.S. rate.

The employment rise in Europe over the last ten years can partly be explained by efforts to make labor markets more flexible and to reduce pension benefits. In one example of increased flexibility, reforms in 2003-05 in Germany and Italy that deregulated the market for temporary employment contributed to a marked rise in employment.

The narrowing of the employment gap since 2007 is due to the stark difference in how the two regions responded to output declines during the recession. The employment rate fell by only 1 percentage point in Europe, despite an output decline of almost 4 percent. In contrast, output decreased less dramatically in the United States (by 2.5 percent), but the country lost many more jobs—the employment rate declined 4.0 percentage points. This difference is likely due in part to European restrictions on firing workers and programs that encourage work sharing, most notably in Germany (see, for example, a recent analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland).

What are the prospects for the employment gap in the coming years? It is quite possible that the closing of the gap due to the fall in U.S. employment rates during the downturn will be reversed as the economic recovery continues and the United States begins to add jobs more rapidly. Still, the increase in Europe’s employment rate, particularly for women and older workers, represents a steady change over the past decade as the rate neared the U.S. rate. The influence of this development on the narrowing of the employment gap is unlikely to be substantially reversed.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect th

e position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

A persistent slowdown in GDP growth is the key factor behind the downward trend in the employment rate since 2000. Specifically, average annual GDP growth from 2001 to 2007 was roughly 1 percentage point slower than growth from 1991 to 2000. In addition, one can argue that slow growth gave firms more leeway to increase production through reorienting the workplace instead of hiring additional workers. As a result, somewhat stronger labor productivity growth in the 2000-07 period was a contributing factor behind the disappointing employment gains.

If you look at the first graph (Total Employment-to-Population Ratio), it seems that the employment ratios in both Europe and the US were trending up more or less in tandem until 2000, but beginning in 2000, long before the financial crisis of 2007, the employment ratio in the US started to decline. How do you explain the US employment ratio decline between 2000 and 2007?