Rajashri Chakrabarti and Noah Schwartz*

Over the past two decades, state and federal education policies have tried to hold schools more accountable for educating their students. A common criticism of these policies is that they may induce schools to “game the system” with strategies such as excluding certain types of students from computation of school average test scores. In this post, based on our recent New York Fed staff report, “Vouchers, Responses, and the Test Taking Population: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Florida,” we investigate whether Florida schools resorted to such strategic behavior in response to a voucher program. We find some evidence that Florida’s schools strategically reclassified weak students into exempt categories, and we draw some lessons that are applicable to New York City’s education policies.

The Florida Opportunity Scholarship Program, enacted in June 1999, made all students of a public school eligible for vouchers (or “opportunity scholarships”) to attend private schools if the school received two “F” grades in a period of four years. The program can be viewed as a “threat of voucher” program. A school receiving an “F” grade for the first time was exposed to the threat of vouchers, but vouchers were implemented only if the school received a second “F” grade within the next three years. Since vouchers were associated with a loss in revenue and negative publicity, threatened schools had a strong incentive to try to avoid a second “F” grade.

While the scores of all regular students were included in the computation of school grades, scores of certain limited-English-proficient (LEP) students were excluded, as were scores of students in many categories of special education. Did this provision of the law induce schools to reclassify their low-performing students into exempt categories so as to artificially inflate scores?

To examine whether the threat of vouchers induced schools to reclassify students in this manner, we consider the fact that there was a sharp discontinuity in how the threat of vouchers was applied. Schools that scored below a fixed cutoff received an “F” grade, and thus the threat, while schools that scored above the cutoff did not. By comparing the schools that fell just below the cutoff to those just above, we get an estimate of the effect of the threat of vouchers. These two groups were nearly identical in terms of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Thus, we are comfortable with the supposition that the only difference between them was that one group was subjected to the threat of vouchers while the other was not.

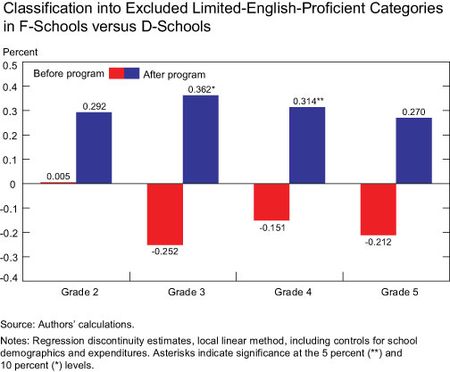

Using this strategy, we find evidence that schools threatened by vouchers tended to classify a larger percentage of their students into the excluded LEP category. We focus on the elementary grades; grades 4 and 5 were the tested grades during this time period in Florida. The figure below shows the share of students classified into the excluded LEP category in threatened schools (which were just below the cutoff) versus non-threatened schools (which were just above the cutoff) in various grades, in the first year after the program went into effect (1999-2000). In Grade 4—the first tested grade—the threatened schools classified an additional 0.31 percent of their students into the excluded LEP category than did non-threatened schools. In addition, we find that in grade 3 (the entry grade to the tested grades), the threatened schools classified an additional 0.36 percent of their students into the excluded LEP category. Both numbers are statistically different from zero. These findings suggest that F-schools were attempting to remove certain students from the test-taking pool by classifying them into the excluded LEP category. When we compare these two groups of schools in the year before the voucher program went into effect (1998-99), we observe no evidence of any additional classification by the soon-to-be-threatened group in the excluded LEP category (red bars in the figure below) in any of the grades, supporting the notion that the observed spike in excluded LEP classification in 1999-2000 was induced by the program.

The numbers above imply that the threatened schools tended to classify an additional 2.6 students in grade 3 and an additional 2.3 students in grade 4 into the excluded LEP category. These numbers are modest. While this strategy alone would probably not enable lower-end F-schools to make a “D” grade, schools close to and just below the cutoff could see this strategy make a difference. Note also that the strategy we use captures the effect of the program on schools that were close to the cutoff. Thus, schools situated far from the cutoff may not have taken these strategic steps.

In contrast, we find no evidence of reclassification of students into excluded special education categories. This is not surprising because there were larger costs associated with such reclassification compared to reclassification into LEP. The main cost was posed by Florida’s McKay Scholarship Program for Students with Disabilities. This program made every disabled student in Florida public schools eligible for vouchers. So reclassification posed the risk that schools would lose the reclassified students and the revenue associated with them.

The Florida experience yields important lessons for accountability policies in our region. New York City’s accountability policy, the Progress Report policy, and the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) law were both modeled on the Florida program, but with important differences. As in Florida, New York City assigns schools letter grades on a scale of A to F, based in part on student performance on standardized tests. These grades are published in annual Progress Reports and result in credible rewards and sanctions. However, unlike the Florida program, New York City’s program holds schools accountable for all English language learners (ELLs) and Special Education students. Moreover, New York City Progress Reports give schools extra credit for achieving progress for ELL and Special Education, as well as other high-needs groups (for example, students in the lowest third citywide). Like New York City’s Progress Reports, the federal NCLB law holds schools accountable for the performance of all students, including LEP students and students with disabilities. These program features are important steps forward in that they serve to eliminate adverse incentives for the type of strategic reclassification that took place in Florida.

The general lesson is that policymakers must be careful when designing exemptions or special allowances for certain groups of students, as these accommodations can create adverse incentives and unintended consequences. While accountability policies must acknowledge the challenges schools face in educating students with limited English proficiency, disabilities, and other special needs, excluding these students entirely from accountability measures may induce struggling schools to reclassify low-performing students into the exempted categories. Such strategic steps may not improve the quality of education for the groups in question or for the reclassified students.

*Noah Schwartz is a former assistant economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics