Over the next few years, large volumes of homes are likely to flow from foreclosure onto lenders’ balance sheets as “real estate owned,” or REO. Without a significant boost to demand, this large volume of “distressed” real estate could potentially put substantial downward pressure on home prices. Accordingly, new policy initiatives are needed to increase the rate at which properties that flow into REO get reabsorbed back into use as renter- or owner-occupied units. In this post, I make the case for a tax credit for Gulf War II veterans’ home purchases.

In late 2009 and early 2010, homebuyer tax credits provided a much-needed boost to home sales, thereby helping to stabilize home prices. My proposed homebuyer tax credit would be targeted at Gulf War II veterans who purchase properties out of the REO inventories of the various mortgage lending entities of the federal government—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

The Foreclosure-REO Pipeline

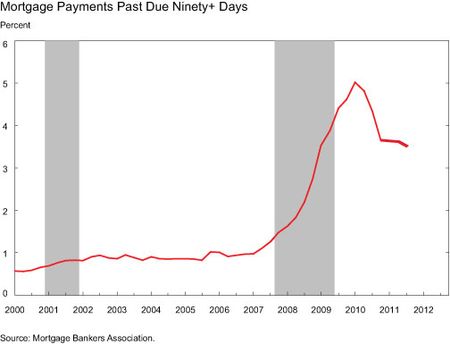

The chart below shows the percentage of first mortgage loans that are ninety or more days past due. While still quite high by historical standards, the figure peaked at around 5 percent in early 2010 and has been gradually declining since then. This decline has led some to conclude that the worst of the housing crisis is behind us. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Indeed, it is quite likely that the number of homes flowing onto lenders’ balance sheets in 2012 and 2013 will be considerably larger than was the case in either 2010 or 2011.

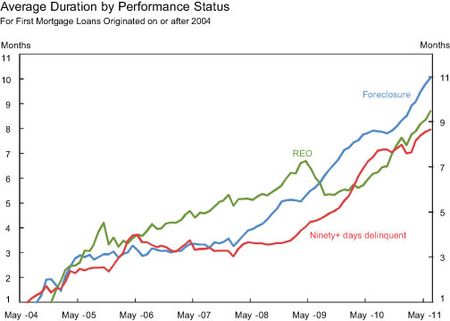

My conclusion is based on an analysis of a representative sample of first mortgage loans. This sample provides information about the current performance status of each loan, indicating whether it is current; thirty, sixty, or ninety+ days delinquent; in foreclosure; or in the lenders’ REO portfolio. The first part of the analysis determined what has happened to the average number of months (duration) that loans are staying in these categories. As shown in the next chart, these average durations have increased dramatically over the past few years. For example, as of mid-2011, the average number of months a loan stayed in the foreclosure process was eleven, up from around three in 2006 and 2007. Similar increases occurred for the number of months in the ninety+ day category and in REO.

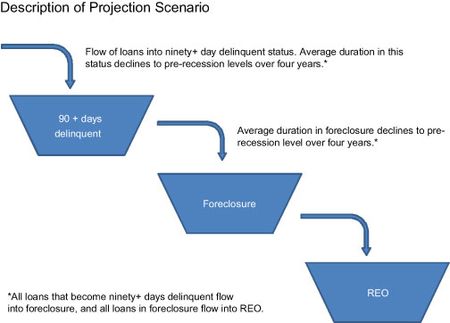

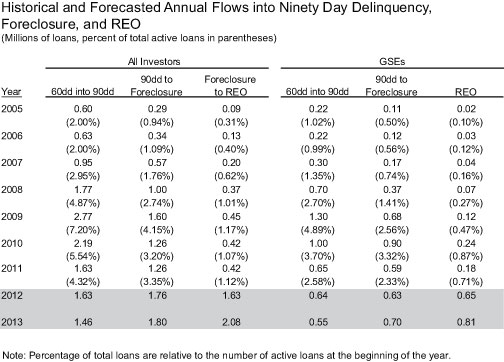

But what will happen when these durations level off and then begin to decline back toward their long-term averages, as seems likely to occur over the next few years? To try to answer that question, we developed the following scenario (summarized in the next chart). Suppose that the number of loans flowing into ninety+ day delinquency and the average duration that a loan stays in that status before flowing into foreclosure return to their pre-recession averages gradually over the next four years. Similarly, assume the average duration in foreclosure before flowing into REO returns to its pre-recession average over four years. To simplify the analysis, these projections assume that all loans that become ninety+ days delinquent flow into foreclosure, and all loans in foreclosure flow into REO.

The results, presented in the table below, are quite sobering. Roughly 1.6 million properties—four times the volume of 2010 and 2011—would flow into REO in 2012, with even more in 2013. Of that REO flow, about 40 percent would be to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

While actual events will likely differ from this scenario, the analysis suggests that the bulk of the REO problem facing the nation lies ahead of us. This possibility represents a significant downside risk for the U.S. economy. The large supply of distressed real estate would, all else equal, put downward pressure on home prices. This in turn would further reduce household net worth, likely depressing consumer spending. Moreover, with large numbers of homeowners in a negative equity position—with total mortgage debt in excess of the current value of the property that is the collateral for that debt—further price declines could induce some of those “under water” homeowners to stop making their mortgage payments. This risk of further price declines and its consequences informs the expectations of potential homebuyers, homebuilders, mortgage lenders, and others involved in housing transactions, such as appraisers and private mortgage insurers. Thus, just as home prices rose during the boom because everyone involved expected them to continue to increase, we now face the risk that home prices will fall because the behavior of everyone involved is based on the risk that they will fall.

The Case for a Tax Credit for Gulf War Veterans’ Home Purchases

Given the continued high level of unemployment, renewed downward pressure on home prices, and the fact that the risks for U.S. economic growth are skewed to the downside, we are at a critical juncture. Prudent risk management suggests that some new policy initiatives are needed to increase the rate at which the properties that flow into REO get reabsorbed back into use as renter- or owner-occupied units.

I would like to propose one such policy: a “Gulf War II Veterans Home Buyers Tax Credit.” This credit would be modeled on the Home Buyer Tax Credit enacted in November 2009, as discussed below. It would be available to both first-time and long-term homebuyers. However, it would be targeted in two key respects. First, it would be available only to Gulf War II veterans, defined as those who have served in the Armed Forces of the United States since September 2001. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are currently about 2.5 million such veterans. That number will surely grow over the next few years as our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan

winds down. While all veterans are deserving of our gratitude, this particular group is most likely to lag behind their peers who did not serve in terms of wealth accumulation. Second, the credit would be available only for purchases of short sales and REO of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the FHA, and the VA. Such a credit would be a “win-win” policy, an expression of the nation’s gratitude for a significant sacrifice, while at the same time speeding the onset of a more robust recovery of the economy. And its net cost to the government is likely to be relatively low. First, the properties eligible for this proposed credit are either already on the balance sheet of the U.S. government, or potentially would be in the case of a short sale. Thus, the government is already exposed to any loss associated with the sale of this real estate. The proposed credit would likely result in some firming of the bid prices for such properties, thereby reducing that potential loss. Second, to the extent that the overall economy benefits, tax revenues would be higher than would otherwise be the case.

Homebuyer Tax Credit Has Boosted Sales and Prices at Relatively Low Cost

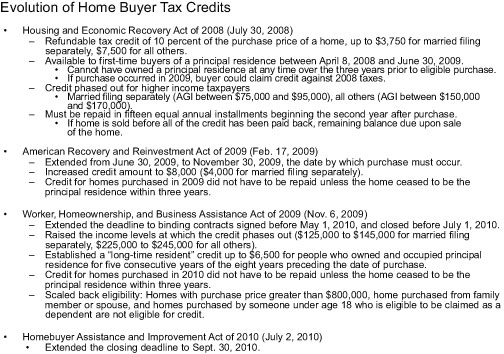

What reasons are there to assume my proposed tax credit would be effective? As summarized in the following chart, in mid-2008 the federal government launched a first-time homebuyer tax credit. In February and again in November of 2009, that credit was expanded in terms of amount and eligibility and extended for a longer period of time.

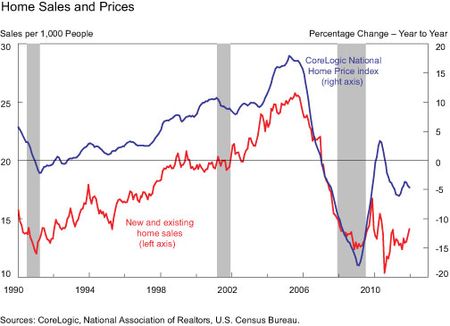

As shown in the chart below, the pending expiration of the credit resulted in a surge of home sales in the closing months of 2009 and again in the spring of 2010. Those surges in home sales resulted in a firming of home prices. Also shown, however, is that home sales currently remain at quite depressed levels and that, as a result, home prices have come under renewed downward pressure. Based on data compiled by the Internal Revenue Service, 1.2 million individual tax returns for 2008 claimed the first-time homebuyer tax credit, and 1.4 million individual tax returns for 2009 claimed either the first-time or the long-time homebuyer credit. The total amount of credits claimed for those two years was $16 billion for an average credit of a little more than $6,000. Comparable data for 2010 are not available at this time, but it is likely that including 2010 data will show the total gross cost to be in the $30 to $40 billion range. The net cost is undoubtedly less, however, given the boost to overall economic activity.

While the positive impact of the tax credit on sales and prices is clearly evident, it has been criticized on two main grounds. First, it is argued that the credit was inefficient because it was provided to taxpayers who would have purchased a home even in the absence of the credit. Second, it is argued that the credit merely pulled forward home sales that would have occurred at a later date. While I acknowledge that there is some truth to these arguments, it can also be argued that the credit helped stabilize home sales and prices at a critical juncture for the U.S. economy. Quite simply, the home buyer tax credit worked! No one can prove the counterfactual, but it is quite likely that the performance of the U.S. economy over the past few years would have been considerably worse absent this boost to the housing market.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

On February 22, 2012, we released this blog post under the title “A ‘Homes for Heroes’ Tax Credit.” The post proposes a home buyer tax credit for Gulf War II veterans who purchase properties out of real-estate-owned inventories of the various mortgage lending entities of the federal government—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. So as not to confuse this proposal with the existing “Homes for Heroes” company and foundation, we now refer to our proposal as the “Gulf War II Veterans Home Buyers Tax Credit.”

Homes for Heroes is a registered trademark, so that won’t work. But really enjoyed your analysis here.