João A.C. Santos

In yesterday’s post, Nicola Cetorelli argued that while financial intermediation has changed dramatically over the last two decades, banks have adapted and remained key players in the process of channeling funds between lenders and borrowers. In today’s post, we focus on an important change in the way banks provide credit to corporations—the substitution of the so-called originate-to-distribute model for the originate-to-hold model. Historically, banks originated loans and kept them on their balance sheets until maturity. Over time, however, banks began increasingly to distribute the loans they originated. With this change, banks limited the growth of their balance sheets but maintained a key role in the origination of corporate loans, and in the process contributed to the growth of nonbank financial intermediaries.

Banks started distributing the corporate loans they originated by syndicating loans and also by selling them in the secondary loan market. In loan syndications, the lead bank—the bank that sets the terms of the loan—usually retains a portion of the loan and places the remaining balance with a number of investors—the syndicate participants—which are usually other banks. This is done in conjunction with, and as part of, the loan origination process. In contrast, the secondary loan market is a seasoned market in which banks, including lead banks and syndicate participants, can subsequently sell an existing loan. The spectacular growth of the market for collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) in the years that preceded the financial crisis brought about an important increase in the demand for corporate loans, giving banks an opportunity to distribute larger portions of the loans they originated. Prior to 2003, the annual volume of new CLOs issued in the United States rarely surpassed $20 billion. Since then, loan securitization has grown rapidly, surpassing $180 billion in 2007.

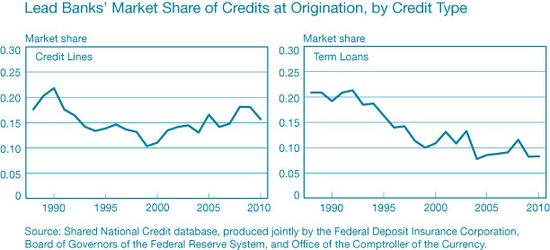

As the figure below shows, over the last two decades, banks increasingly adopted the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending business, particularly when they originated term loans. To track banks’ loan activity over time, we rely on a novel data source, the Shared National Credit (SNC) program. This program—run by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency—collects information on all credits that exceed $20 million and are held by three or more federally supervised institutions. According to SNC data, in 1988, lead banks—including commercial banks, bank holding companies, thrifts and thrift holding companies, credit unions, and foreign banking organizations—retained in aggregate 18 percent of the credit lines and 21 percent of the term loans they extended in that year. By 2006, the last year before the data pick up the effects of the most recent financial crisis, lead banks had lowered their market share to 14 percent of the credit lines they originated, and decreased their market share of the term loans they originated to 9 percent.

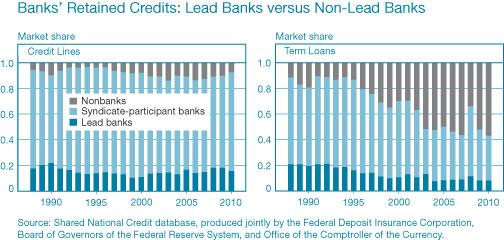

However, the decline in lead banks’ market shares of credit lines and term loans reflects only part of the effect of banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending business, because it does not account for the role that participant banks play in this business. As we show in the figure below, although the market share of credit lines retained by lead banks decreased through the 1990s and increased through the 2000s, total market share held by all banks (both lead and participant) remained fairly stable at an average of 92 percent during the pre-crisis sample period. In other words, credit line provision continues to be in essence a “bank business.” In the case of term loans, however, the decline in the lead banks’ aggregate retained share was accompanied by an even bigger decline in the share of the term loans acquired by other banks. Of the $47 billion term loans originated in 1988 that are covered in the SNC program, lead banks and participating banks together retained on their balance sheet 89 percent of the amount of credit. Of the $315 billion term loans originated in 2007, banks retained on their balance sheet only 44 percent.

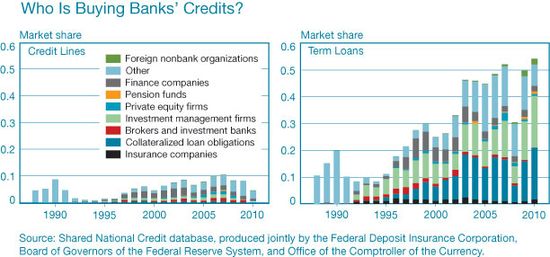

The figure below shows that the decline in the portion of the term loans originated by banks that stayed in the banking sector was accompanied by an increase in the presence of nonbank investors in this market, in particular finance companies, CLOs, and investment managers. In the early 1990s, none of these investors had a meaningful presence in the market for term loans originated by banks. However, by 1998, finance companies already accounted for 7 percent of the term loans originated in that year. While the presence of these companies declined somewhat in the following year, CLOs and investment managers continued to increase their market share and, by 2007, these investors acquired 14 percent and 16 percent, respectively, of the term loans originated by banks in that year.

Banks’ increasing use of the originate-to-distribute model in their corporate lending business is important for several reasons. As shown in Bord and Santos (2011) , there is evidence that allowing lead banks to retain less “skin in the game” can affect their loan underwriting standards and possibly contribute to riskier lending. By increasing the number and diversity of investors in loans, banks’ use of the originate-to-distribute model may also hinder corporate borrowers’ ability to renegotiate their loans. In addition, it will make the credit that banks keep on their balance sheets increasingly less representative of the role they perform in financial intermediation in general and in the process of extending credit in particular.

Lastly, it will transfer an impor

tant portion of credit risk out of the banking system. In 1993, of the $22.7 billion in term loans that banks originated, they sold $2.2 billion to CLOs, brokers and investment banks, investment managers, private equity firms, finance companies, and foreign nonbank institutions—the so-called “shadow banking” system. In 2007, of the $315 billion term loans that banks originated, they sold $125 billion to these same nonbank institutions. Thus, over a period of roughly fifteen years, the annual volume of term loans and the corresponding credit risk that banks transferred out of the banking system increased by more than $120 billion. While the impact this transfer may have on the stability of the entire financial system and the availability of credit to corporations is still unclear, its contribution to the growth of nonbank financial intermediaries, including that of the unregulated shadow banking system, is apparent.

Nevertheless, the evidence we have presented shows that, notwithstanding the spectacular growth of nonbank financial intermediaries in the last decade, banks retained the pivotal role of credit originators and liquidity providers to corporations through their credit line activity, and consequently retained their influential role in financial intermediation.

In tomorrow’s post, Don Morgan, Benjamin Mandel, and Jason Wei will pursue this investigation of the important role banks continue to play in financial intermediation by looking at banks’ role as credit enhancers along the credit intermediation chain.

João A.C. Santos is a vice president in the Financial Intermediation Function of the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics