Jason Miu, Asani Sarkar, and Alexander Tepper

Against the backdrop of the ongoing debt crisis in Europe, the difficulties faced by European banks in borrowing U.S. dollars have attracted increased attention. The inability to borrow dollars has been partially responsible for European banks’ decisions to sell dollar-denominated assets and reduce their lending activity in the United States, to the possible detriment of U.S. companies and global financial markets. In this post, we discuss the genesis of European banks’ dollar funding gap problem and the steps taken by central banks to help fill this gap. While we focus on European banks in this post, our discussion applies more generally to global banks that rely on short-term, foreign currency borrowings.

The Sometimes Fragile Dollar Funding Model

Euro-area banks have accumulated sizable holdings of U.S. dollar assets in the past decade, amounting to $3.2 trillion at the end of fourth-quarter 2010, according to ECB estimates. The growth in dollar assets can be attributed partly to the increased globalization of capital markets during this period. In addition, the international role of the dollar as a medium of exchange in global trade has contributed to the dollar exposure of non-U.S. banks, as European institutions made dollar-denominated loans to support international transactions.

Some European banks finance their U.S. dollar assets by opening a commercial bank in the United States and issuing dollar deposits, much like a U.S. bank would. However, building a retail deposit base and qualifying for federal deposit insurance entails significant costs and challenges. Therefore, most European banks choose to meet their dollar funding needs by issuing dollar-denominated wholesale debt—such as certificates of deposits and commercial paper—from their foreign bank branches and other corporate entities that are not federally insured.

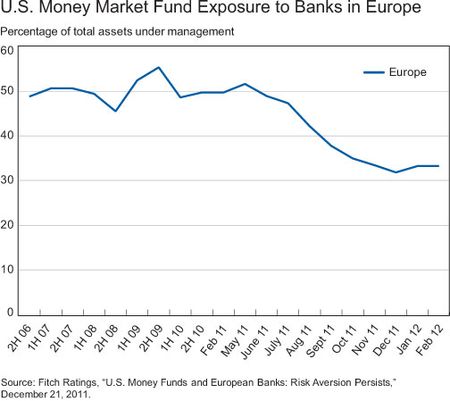

While the European banks’ dollar-funding model may work well in normal times, it often proves fragile during crises. The reason is that much of the funding includes short-term, uninsured debt that leaves debt-holders exposed when banks face economic difficulties. In particular, U.S. money market funds (MMF) that are the main holders of this debt can withdraw from further debt purchases prior to deteriorations in the perceived credit quality of banks either because they fear other money funds will also withdraw, or more often because they fear such exposures could result in redemptions by their own customers. Such a pullback occurred during the subprime crisis here in the United States and has recurred during the ongoing European debt crisis. Estimates from Fitch Ratings indicate that, from May 2011 to December 2011, the ten largest U.S. MMFs reduced their exposure to European banks by 45 percent. As a result, MMF exposure to Europe, as a share of total assets, has fallen from 55 percent in the second half of 2009 to about 33 percent in February 2012 (see chart below).

Minding the Gap

Faced with reduced demand for their dollar-denominated debt, European banks explored other ways to bridge their dollar funding gap. Some banks reduced their dollar assets (for example, by selling assets or reducing lending) so as to lessen their need for dollars. Others borrowed dollars either through their U.S. branches from the Fed’s liquidity facilities, such as the Term Auction Facility, when it was still operational, or locally from their own central banks under the central bank swap lines.

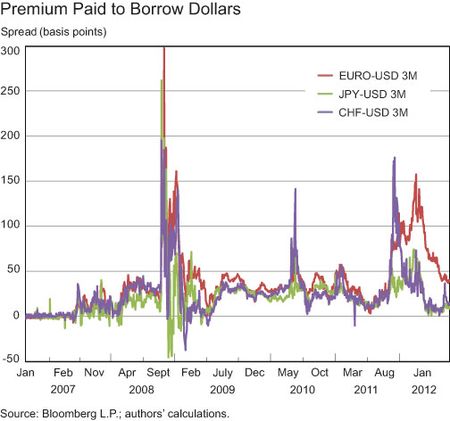

The most widely used alternative was for European banks to convert their euro liabilities into dollars for a fixed period of time by way of FX swaps. For example, European banks could issue euro-denominated debt and then swap the euros for dollars at the going current exchange rate, while agreeing to swap those currencies back at a pre-agreed exchange rate in the future. While the use of FX swaps is difficult to track due to the lack of data, Fender and McGuire estimate that about half the dollar funding gap of European banks was met through FX swaps. Increased activity by European banks in the FX swap market to obtain dollars is reflected in the higher costs of using the swaps, which is given by the premium that banks are willing to pay to borrow dollars rather than euros.

In the chart below, we show estimates of the premium (over Libor) to borrow dollars through the FX swap market. This premium is measured by the additional interest rate paid to borrow euros and exchange them for dollars in the FX market, after hedging (or offsetting) the FX risk. Banks are assumed to borrow at the Libor interest rate. When markets function well, as in normal times, arbitrageurs ensure that the premium is close to zero by lending in the more expensive currency (for example, dollars) and borrowing in the cheaper currency (for example, euros). Indeed, the euro-dollar premium was close to zero before the start of the financial crisis in August 2007, but it has become persistently positive since then, with the highest levels coming at times of the most financial stress. For example, the euro-dollar premium exceeded 200 basis points, or 2 percent, after Lehman Brothers failed and exceeded 100 basis points, or 1 percent, as the European debt crisis intensified. The premium was also high when banks exchanged Japanese yen for dollars (that is, the yen-dollar premium) or Swiss francs for dollars (that is, the franc-dollar premium). The high dollar premium with respect to different currencies shows that the dollar shortage during the recent financial crisis was global.

Central Bank Swap Facilities

In response to dollar funding strains, the Fed, in coordination with other central banks, implemented in December 2007 temporary reciprocal currency arrangements, or central bank liquidity swaps. Under these arrangements, the Fed provides dollars to foreign central banks in exchange for an equivalent amount of foreign currency based on prevailing market exchange rates for a predetermined period. The foreign central bank then makes dollar loans to banks in its jurisdiction. Since this provision of dollars is intermediated through the foreign central bank, the Fed’s credit risk is minimized.

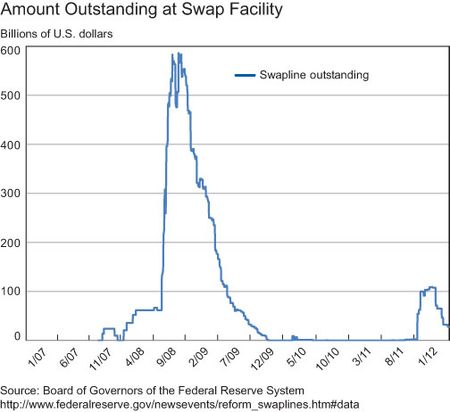

To help improve liquidity in dollar funding markets, central banks made loans at rates that made it attractive for banks to borrow in times of crisis, but not during more normal market conditions. Consequently, banks borrowed heavily from the dollar swap facilities. For example, the amount outstanding of central bank liquidity swaps reached a peak total of $586 billion as of December 2008 (see chart below), as the facility expanded to accommodate rising tension in the offshore dollar markets. Evidence suggests that the swap lines, along with other liquidity facilities introduced by the Fed such as the Term Auction Facility, helped reduce the dollar premium and contained dollar funding pressures in the interbank markets.

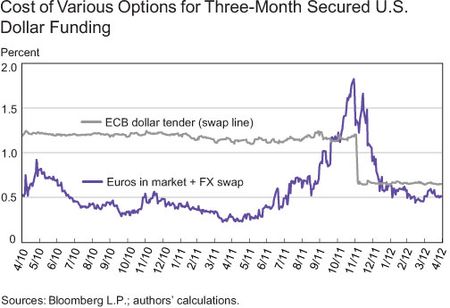

More recently, in May 2010, the central bank liquidity swaps were reintroduced in response to the reemergence of strains in the short-term dollar funding markets. However, until December 2011, banks made little use of the facility compared with earlier periods (see chart above). One possible explanation could be that the cost of borrowing from the swap facility exceeded the cost of borrowing dollars by way of the FX swap market for most banks (see chart below). Banks may therefore have felt that the market would perceive borrowing from the facility as a sign of financial weakness.

Then, in November 2011, the cost of borrowing in the market began to rise sharply to a level well above the cost of the swap lines (see chart above). To ensure that banks did not avoid the swap facility due to any perceived stigma, and to mitigate the risk that dollar funding strains could impact the supply of credit to U.S. households and businesses, the Fed and other central banks agreed to reduce the borrowing rate on the dollar liquidity swaps by 50 basis points on November 30, 2011. Banks resumed borrowing from the swap facility, as indicated by the amount outstanding which increased from essentially zero for most of 2011 to about $109 billion as of January 2012 (see earlier chart). Since the announcement, the euro-dollar funding premium has decreased about 120 basis points from its recent peak of about 157 basis points (see earlier chart).

The continuing dollar funding problems faced by European banks originate from the fragility of their dollar funding mechanism. Through the past few years, central banks have supplied dollar liquidity through the swap facility to successfully ease pressures in the dollar funding markets. Recently, the European Systemic Risk Board has called for a more structured approach to prevent a repeat of dollar funding strains in the future. Such an approach might include closer monitoring and supervision of European credit institutions, better data on dollar funding gaps, and contingency funding plans.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jason Miu is a senior trader/analyst in the Market Operations, Monitoring, and Analysis Function of the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Money and Payments Studies Function of the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Alexander Tepper is a senior trader/analyst in the Market Operations, Monitoring, and Analysis Function of the New York Fed’s Markets Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Are any forms of collateral other than currency offered to secure swap lines through central banks? Assuming an absolute worst case scenario in which the euro were to become defunct, the Fed would be left holding worthless currency. How would it get those dollars back?

I think the inability to borrow dollars has been partially responsible for European banks’ decisions to sell dollar-denominated assets and reduce their lending activity in the United States. While the European banks’ dollar-funding model may work well in normal times, it often proves fragile during crises…