Marco Cipriani, Michael Holscher, Antoine

Martin, and Patrick E. McCabe

In a June post, we explained why the design of money market funds (MMFs) makes them prone to runs and thereby contributes to financial instability. Today, we outline a proposal for strengthening MMFs that we’ve put forward in a recent New York Fed staff report. The proposal aims to reduce, and possibly eliminate, the incentive for investors to run from a troubled fund, while retaining the defining features of money market funds that make them popular financial products. U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, in a recent letter to the Financial Stability Oversight Council, requested that it consider an idea similar to what we described in our staff report as one of several potential options for reforming MMFs to address their structural vulnerabilities.

Key Features of the Minimum Balance at Risk

Our proposal would allow MMFs to maintain a stable $1 net asset value and to provide investors with liquidity on demand. But a small fraction of an investor’s balance, which we call the minimum balance at risk (MBR), would be available for redemption only with a delay. The MBR could be, for example, 5 percent of an investor’s maximum balance over the previous thirty days. That proportion should be large enough and the delay long enough to ensure that redeeming investors share any costs of their redemptions and any imminent portfolio losses with nonredeeming investors. With an MBR in place, redeeming investors wouldn’t be able to eliminate their entire MMF exposure immediately; as a result, the incentive to run would be reduced.

To further reduce the vulnerability of MMFs to runs, we propose that a portion of a redeeming investor’s MBR be subordinated to nonredeeming investors’ shares. Subordination, which would only affect the allocation of losses in the unlikely event that a fund “breaks the buck” and is liquidated, assures that if an MMF does suffer losses, redeeming investors absorb them before nonredeemers do. Thus, subordination creates an actual disincentive to run and gives investors a trade-off between preserving liquidity by redeeming and preserving principal by keeping shares in the fund. (Under current rules, fast-redeeming investors preserve both liquidity and principal at the expense of nonredeeming investors.)

The MBR and Investors’ Incentive to Run

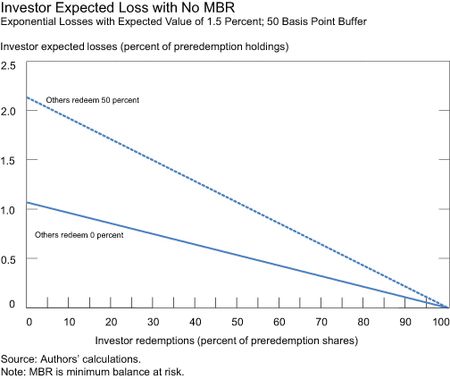

Our staff report shows how the minimum balance at risk affects

investors’ incentives to run by examining how the MBR rule shifts the

allocation of any fund losses between redeeming and non-redeeming investors. The chart below shows how, under current rules, an MMF shareholder’s expected losses vary both with her own redemptions just before a break-the-buck event and with redemptions of other shareholders. We estimate shareholders’ expected losses using historical data on MMF losses, including new data from 2008. (This new information shows that at least twenty-nine MMFs would have broken the buck in 2008 without discretionary support from their sponsors; in our report, we provide a detailed explanation of how expected losses are calculated.)

The chart plots a shareholder’s expected losses when other investors don’t redeem their shares (solid line), and when other investors redeem 50 percent of their shares (dotted line). Both lines are downward sloping: the more an investor redeems, the smaller her losses, and losses are eliminated if the investor redeems all of her shares. The incentive to run is clear. Moreover, incentives to redeem are magnified by the costs of others’ redemptions. As these redemptions increase, the shareholder’s expected losses increase (note how the dotted line lies above the solid line), unless she has redeemed all of her shares.

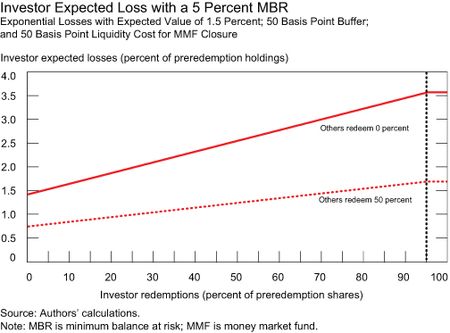

What happens with the MBR? As the next chart shows, even if an investor redeems all of her shares just before a fund breaks the buck, her expected loss isn’t zero, since some of her balance remains in the fund. (While our paper discusses several versions of the MBR, we show expected losses here only for the “strong” MBR rule.) And subordination causes expected losses to grow as her redemptions increase, regardless of the behavior of other investors. That is, because redemption leads to subordination of an investor’s MBR, she minimizes her own expected loss by staying in the fund, rather than joining a run.

Another benefit of the MBR with subordination is that other investors’ redemptions reduce a remaining investor’s expected loss (the dotted line in second chart lies below the solid one). The subordinated MBRs of redeeming investors provide other investors with some loss-absorbing protection that helps compensate for the liquidity costs that redemptions impose on an MMF. In particular, retail investors, who traditionally have been less quick to run from distressed funds, would enjoy greater protection if they don’t run.

Because the risk of losses in an MMF is usually remote, the MBR would have little impact on investors’ incentives to redeem in normal circumstances. However, if losses become more likely, the disincentive to redeem would strengthen. Creating a disincentive to redeem when an MMF is under strain is critical to protecting it from runs. In addition, discouraging redemptions from money market funds during a crisis would help avoid the need for “fire sales” of assets and make money fund losses less likely. More important, it also would limit contagion from one troubled MMF to the rest of the industry.

The Implementation of the MBR

Because an MBR would be in place at all times, investors couldn’t avoid redemption limits by pulling money out just before a crisis. Thus, the proposal has some critical advantages over options that would impose restrictions on shareholders only when an MMF falls into distress. Those conditional restrictions create incentives for investors to redeem even more quickly than under current rules—that is, investors may run from funds preemptively before conditions are met for imposing fees or restrictions. But even with an MBR that’s always in place, money market funds could maintain the features that shareholders value, including the stable $1 share price, market-based yields, and liquidity on demand for almost all of their balances. Indeed, most regular transactions would be unaffected by our proposal, and an investor’s ability to use the MMF for cash management wouldn’t be diminished as long as her balance exceeds or equals her MBR.

In our staff report, we note that redemptions from poorly run MMFs provide market discipline and convey valuable information to markets. Importantly, the MBR wouldn’t discourage redemptions from such funds. Instead, it would strengthen incentives for early market discipline by clarifying the fact that investors cannot quickly redeem all shares from a fund during a crisis. Hence, the MBR would motivate investors to identify potential problems well before any losses are realized, so the market discipline it encourages would more likely be based on investors’ forward-looking assessments of the riskiness of a fund’s strategy or operations, rather than on headlines that trigger runs.

We go on to describe some modifications to the MBR that could provide additional protections. The MBR would work well in tandem with a capital buffer that absorbs losses. Even a relatively small buffer that absorbs only routine price fluctuations could be useful in eliminating MMFs’ ability to redeem shares at $1 when their underlying value is less. We also suggest exempting the first $50,000 of an investor’s redemptions from subordination, so that most transactions by retail investors—who are less prone to run from troubled MMFs—would not trigger subordination.

MMFs present a policy challenge. Although they are important intermediaries for short-term funding and popular cash-management vehicles for retail and institutional investors, the funds are vulnerable to runs that can harm investors and the financial system. The adoption of an MBR rule could significantly reduce the risks that MMFs pose during crises while preserving their important role in the financial markets.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Marco Cipriani is a senior financial economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael Holscher is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Financial Institution Supervision Group.

Antoine Martin is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Patrick E. McCabe is a senior economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics