Dafna Avraham, Tara Sullivan, and James Vickery

The New York Fed has recently published the first edition of a new quarterly report tracking the aggregate financial condition of consolidated U.S. banking organizations. In this post, we describe the methodology used to construct the statistics in the report as well as present and briefly discuss some of the findings.

Banks versus Bank Holding Companies

The new report, “Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking Organizations,” is based on regulatory accounting data filed by U.S. commercial banks and bank holding companies (BHCs). This latter term may be unfamiliar to some readers—a BHC is simply a parent corporation that controls one or more banks. Importantly, BHCs also often control a range of other nonbank financial subsidiaries, such as

broker-dealers, asset management firms, and insurance firms. Each of the

largest U.S. banking organizations is organized according to a BHC structure.

The “Quarterly Trends” report presents aggregate industry trends in profitability, assets, capital, and so on, constructed by summing up consolidated accounting data across all U.S. commercial banks and BHCs. This approach distinguishes this report from the more detailed “Quarterly Banking Profile” prepared by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which focuses only on banks and doesn’t account for nonbank subsidiaries of BHCs.

The distinction between the two concepts is important, because, as discussed in a 2012 research

paper by Avraham, Selvaggi, and Vickery, around 30 percent of aggregate banking industry assets are held outside firms’ bank subsidiaries. This percentage is much larger for some of the largest banking organizations and for particular types of income and assets.

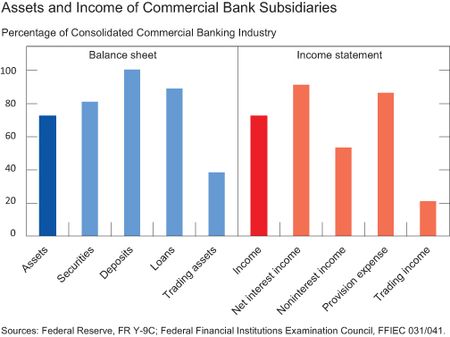

To illustrate this point, the chart below plots the percentage share of the banking industry represented by commercial banks, for different balance sheet and income statement variables. (Remember, the remainder reflects the activities of nonbank BHC subsidiaries.) Notably, nearly all loans and deposits are owned by firms’ banking subsidiaries. Other categories, however, such as trading income and trading assets, are concentrated outside of banks. It’s important to consider the entire

consolidated BHC, rather than just its banking subsidiaries, to fully capture

these activities.

Some Trends

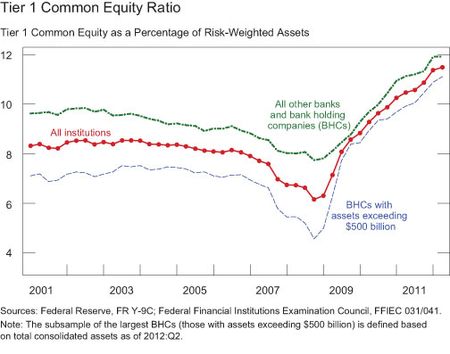

Below we present some time-series charts from the “Quarterly

Trends” report showing the recent evolution of industry capitalization and

profitability. The first chart plots banking industry capitalization, measured

by the ratio of Tier 1 common equity to risk-weighted assets. It illustrates

the striking increase in banking industry capitalization in recent years, due

to the issuance of new seasoned equity by many firms, as well as in retained

earnings. This measure of industry capitalization reached 11.5 percent in 2012:Q2,

compared with a low of 6.2 percent in 2008:Q4.

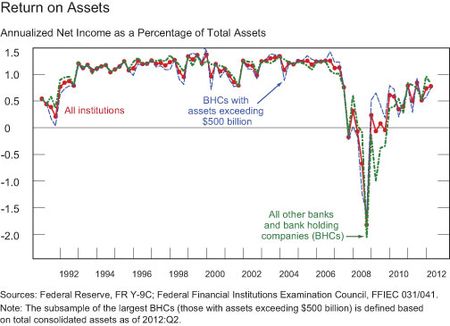

The next chart plots return on assets (ROA), a measure of industry profitability, calculated as annualized quarterly net income as a percentage of total assets. Measured by ROA, banking industry profitability was high and relatively stable in the period before the 2007-08 financial crisis. From 1994 to 2007, industry ROA was generally bounded between 1 percent and 1.5 percent, and was consistently positive, even during the 2002-03 recession. This abruptly changed during the financial crisis, when many banks and BHCs suffered large losses. The commercial banking industry has returned to profitability in recent years, albeit at a lower level of ROA compared with the precrisis period.

Both charts also present a separate time series for the subset of largest banking organizations. We defined “largest” relative to a size cut-off of $500 billion (seven firms exceeded this cut-off as of 2012:Q2: J.P. Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, MetLife, and Morgan Stanley). For consistency, the historical time series for the largest firms reflects available data on this same subset of firms, using a pro forma approach that incorporates premerger data on smaller BHCs that were subsequently acquired by one of these largest firms. While trends across the two banking firm size groups are generally similar, some differences are apparent. For example, the recent increase in capital has been more pronounced for the largest banking organizations.

The full quarterly report presents a larger set of charts

as well as other statistics, such as a table listing the fifty largest banking

firms in decreasing order of size. The New York Fed plans to update these

statistics after each quarter’s bank and BHC regulatory data become available

(normally two to three months after the end of the relevant calendar quarter).

Users of these statistics should be aware of some limitations associated with the data. Perhaps most importantly, for data comparability reasons these statistics only reflect firms organized as commercial banks or BHCs, and don’t include other types of financial firms, such as hedge funds or savings bank holding companies. One example of the issues this can create is that two of the seven largest BHCs—Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley—only began to file bank regulatory data in 2009,

following their switch to a bank holding company charter during the financial

crisis. So the historical time series prior to 2009 doesn’t include these two

firms, since no comparable data are available for them. In the body of the “Quarterly Trends” report, a chart is presented showing total industry asset growth—it’s high during 2009 in part because of the addition of these two firms to the

sample.

These caveats aside, the statistics in the “Quarterly Trends” report represent what we believe is a useful snapshot and historical perspective on the financial condition of consolidated U.S. banking organizations. We hope it will be useful to researchers, analysts, and others interested in these important firms.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Dafna Avraham is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Tara Sullivan is a research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

James Vickery is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics