Rajashri Chakrabarti and Sarah Sutherland

In the state of New Jersey, any child between the ages of five and eighteen has the constitutional right to a thorough and efficient education. The state also has one of the country’s most rigid policies regarding a balanced budget. When state and local revenues took a big hit in the most recent recession, officials had to make tough decisions about education spending. In this post, we analyze education financing and spending in two groups of high-poverty districts during the Great Recession and the ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009) federal stimulus period—the Abbott and Bacon districts. Analysis in our recent New York Fed staff report shows that the Abbott districts exhibited the sharpest declines—relative to trend—in both total funding and total spending per pupil during the post-recession era. Additionally, the Abbott districts were the only group of districts in New Jersey to present statistically significant negative shifts in instructional spending, even with the federal stimulus.

For the Abbott and Bacon districts, the debate over the meaning of thorough and efficient has become a perennial courtroom discussion. The famous Abbott v. Burke litigation was first filed in 1981 on behalf of a group of students from four school districts arguing that funding disparities prevented these poor, urban districts from providing an adequate education. The Abbott litigation over the last two decades resulted in an unprecedented order to the funding system in New Jersey, whereby the state was required to allocate funds to Abbott districts above and beyond what was provided to all other districts.

By the time our data set begins, in the 1998-99 school year, the now 31 designated Abbott districts had received 45 percent of the total state aid funds distributed to all 572 districts. (For simplicity, from now on we’ll use the spring term to denote the school year.) This figure increased to 51 percent by 2005 and remained at 50 percent as of 2010.

Like the Abbott districts, another group of sixteen low-income school districts has been at the center of another series of court cases arguing for equitable education. These districts, known as the Bacon districts, are located in rural areas. Unlike the Abbott cases, the Bacon litigation didn’t precipitate additional funding for those districts.

To mitigate the effects of the recession, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (see Orr and Sporn [2012] for details), a federal economic stimulus package from which New Jersey has received $2.23 billion for education financing. The education portion of the stimulus became available in the 2009-10 school year; by the end of that year, the state had spent nearly all of the funds.

In our analysis, we examine school funding and spending patterns using a rich panel data set and trend-shift analysis. When interpreting these trend shifts, it’s important to note that the recession era coincided with implementation of a new state funding formula enforced by the School Funding Reform Act of 2008 (SFRA). Implementation of the formula marked the first time since 1990 in which there was no special earmark assigned solely for Abbott districts. The formula was instead applied uniformly to all districts. Thus, while the Abbott districts shared the negative effects of the Great Recession faced by all New Jersey school districts, they faced a second negative shock in the form of SFRA.

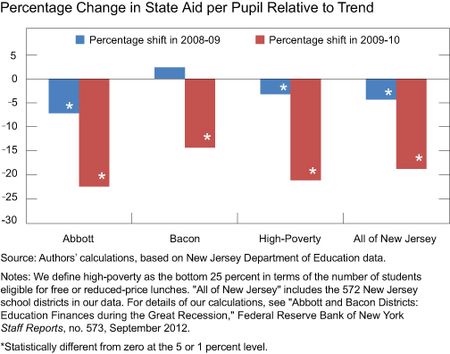

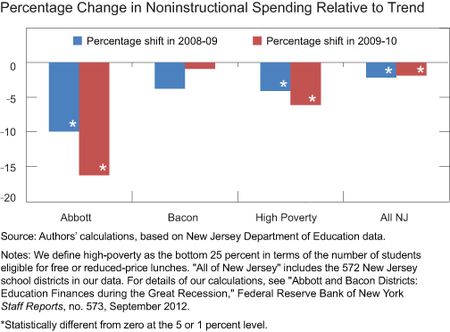

Midway through the 2010 school year, the recession forced some changes to the prescribed SFRA formula. Revenue streams came in at what was projected to be $2.2 billion less than what was needed to cover the state’s projected spending. In an unprecedented move, New Jersey significantly reduced education funding midyear. The funding caps for district aid were cut, and many districts received less state aid than was budgeted and less aid than was required under the SFRA formula. Consequently, relative to preexisting trends, 2010 state aid per pupil showed considerably sharper declines across the board than in 2009, as the chart below shows. The blue bars represent changes from the prerecession trend in 2009 expressed as a percentage of the prerecession base; the red bars indicate changes from the prerecession trend in 2010 expressed as a percentage of the prerecession base. It is noteworthy that these declines were the largest in the Abbott districts in both school years.

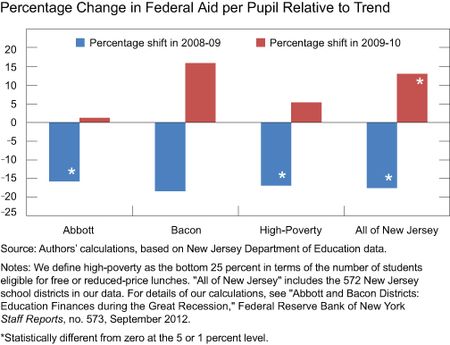

While state aid declined, the ARRA federal stimulus did lead to a positive shift in federal aid per pupil for all of the above groups in 2010. Despite this, the positive trend shift in 2010 was the smallest in the Abbott districts, as shown in the next chart.

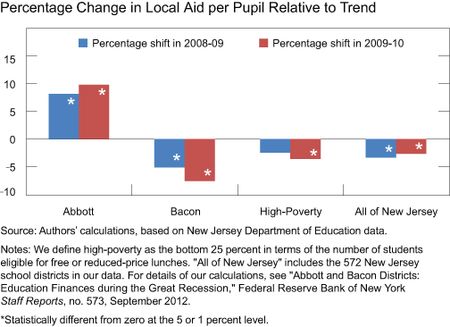

The patterns for property taxes and local aid variables are also interesting. As illustrated in the chart below, unlike school districts in the rest of the state, the Abbott districts showed a significant upward shift in property tax revenues and local aid in 2009 relative to preexisting trends, suggesting that property tax rates were raised in these districts as a way to compensate for the substantial decline in state aid. In contrast, results suggest that the rural Bacon districts had less flexibility to increase property taxes, and they showed the largest significant declines in local aid per pupil.

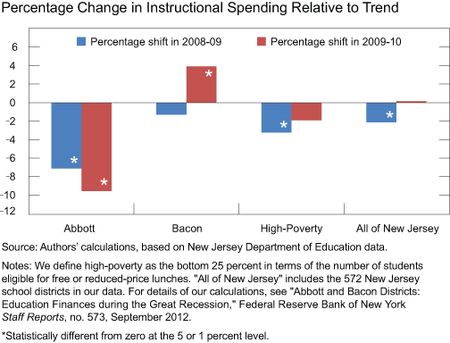

We also investigate patterns in the various components of spending in these groups of districts following the recession. Instructional spending is considered the spending category that matters most for student learning—it includes teacher salaries and classroom spending. Relative to preexisting trends, most New Jersey districts either maintained or exhibited small decreases in this category (see next chart). The picture was very different in the Abbott districts; they showed sharp decreases in both school years. Most noteworthy, they were the only group that saw a large, statistically significant downward shift in instructional spending in 2010, despite the influx of stimulus funds.

In general, spending in the noninstructional categories—such as support services, noninstructional student services, and transportation—saw larger decreases than spending in the instructional category. As might be expected, school administrators strived to preserve instruction first. But even in noninstructional categories, the cuts, relative to preexisting trends, were largest in the Abbott districts.

When SFRA funding equalization among Abbott and non-Abbott districts was declared constitutional, one agreement was that New Jersey would fully fund SFRA for the Abbott districts for three consecutive years. In reality, though, fiscal constraints led to a midyear reduction in funding in the 2010 school year and another in 2011. These funding cuts ultimately led to the twenty-first Abbott v. Burke litigation. The court deemed that the state had yet again failed in its constitutional requirements and ordered a remedy payment of $500 million to the Abbott districts.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows significant declines from trends in public funding and school spending in the Abbott districts. (Note that our study looked only at school financing and didn’t analyze

the impact of these spending changes on educational outcomes.) In the instruction and noninstructional categories, the Abbott districts exhibited the largest decreases from prerecession trends. Moreover, they’re the only group in our expansive analysis to show statistically significant negative shifts in instructional spending in the same year in which New Jersey received an influx of ARRA federal stimulus.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sarah Sutherland is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics