James Orr and John Sporn

Fiscal stimulus, in the form of large discretionary increases in federal spending and tax reductions, is often triggered by a strong and persistent rise in the national unemployment rate. The most recent example was the $860 billion (6 percent of GDP) stimulus contained in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), adopted in the context of rising unemployment rates. The spending components of the program were varied, including federal transfers to state governments to support education and social services, assistance to unemployed and disadvantaged individuals, and funds for capital construction projects. The majority of the stimulus funds were allocated to state governments and, since the program was motivated by high and rising aggregate unemployment, a reasonable expectation would have been that states with high unemployment rates would receive large allocations. Our analysis of the distribution of ARRA funds across states shows that the expanded assistance to unemployed workers was indeed highly correlated with state unemployment rates. It turned out, however, that most other state allocations had little association—positive or negative—with state unemployment rates. The ultimate distribution instead seemed to reflect a number of practical considerations involved in implementing such a vast spending program. In this post, we outline what in our view were the key considerations that governed the distribution of the stimulus spending across states, and we use the example of one component of that spending—highway infrastructure investment—to illustrate how the stimulus funds got to the states.

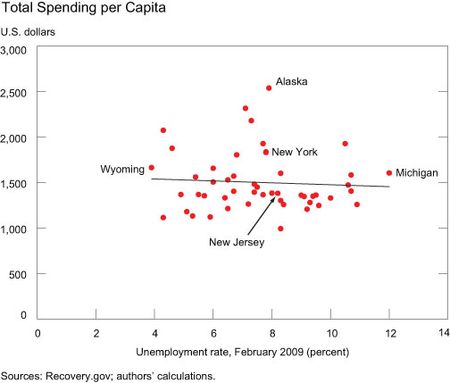

Using per capita stimulus dollars in a state as the spending metric, the scatter plot below shows the lack of correlation between stimulus spending and state unemployment rates at the time the program was introduced. The lack of correlation is also evident in a comparison of spending with the cyclical change in state unemployment rates at the time.

Major federal spending programs challenge policymakers to appropriate large amounts of money efficiently and expeditiously. We believe five practical considerations drove the ultimate allocation of funds, and that each potentially weakened the link between spending and unemployment. The first was competing program goals. The program was designed to create or save jobs, so the distribution of spending reflected, in part, how and where these effects would be most likely to occur. The program also had the stated goal of stabilizing state and local government budgets. In fact, it has been argued in at least two articles that this may have been a more important goal of the program. (See FRBSF Economic Letter and an NBER working paper.) Second was timing, particularly the need to get the spending up and running as quickly as possible. While the ARRA did create one new program, the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, the majority of the spending relied on temporarily augmenting the size of existing federal-aid programs to states while using the existing formulas governing the distribution of that aid. Third was the jobs per dollar of spending. Jobs per dollar of spending differs across programs, so that metric, rather than spending per capita, might be expected to be positively correlated with unemployment rates. Fourth, there was a sense that this stimulus program offered an opportunity for expanded federal funding of infrastructure and education projects that could lead to longer-term economic benefits for states. Finally, equity considerations, both within and across programs, implied that each state should receive some funds and that no state should have an average level of spending that was too far from the mean.

The distribution of the $27.5 billion of aid to states through the Federal Highway Administration of the Transportation Department illustrates the allocation process. The spending was specifically allocated for projects that restore, repair, and construct federal highways. The funds had to be spent within three years and, for large metro areas, had to be consistent with the relevant metropolitan area transportation plan. Similar aid had been provided by the federal government to states for a number of years. The aid constituted 5 percent of total ARRA spending, and the projects were 100 percent federally funded.

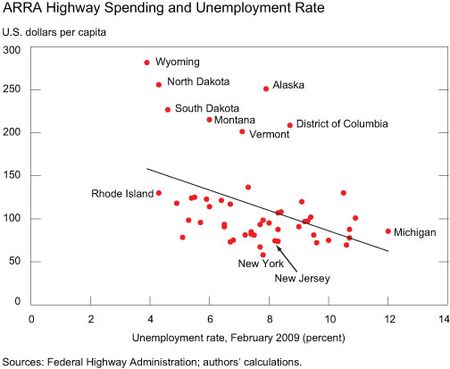

The allocation of ARRA aid was determined as follows: The program set aside $1 billion for aid to Native American reservations and federal lands, on-the-job-training programs, Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories, and administrative expenses. Of the remaining funds, roughly 50 percent was distributed to states based on the formula used to distribute highway aid in 2008, and 50 percent was distributed based on each state’s share of total lane miles (25 percent), total vehicles miles traveled (40 percent) on federal-aid highways, and each state’s share of the taxes paid by highway users (35 percent). There were also some funds set aside for sub-state areas with a population of less than 200,000. The graph below shows that this allocation formula led to highway spending across states that did not have a positive relationship with unemployment rates.

The increase in spending on federal-aid highways, nevertheless, could be viewed favorably from several standpoints. There was an effort to make the spending equitable in that there were initial set-asides for segments of the population, and then all states with federal-aid highways received funding. The spending was timely, aided by the use of existing highway funding allocating formulas and existing project eligibility guidelines. Also, there are potentially positive long-term economic impacts of the funding from an improvement in state transportation infrastructure.

In sum, practical considerations in targeting new federal spending under a vast program like the ARRA led to spending that was less linked to state unemployment rates than might be expected. Estimates vary as to the effects of the ARRA, but larger questions remain. Did the particular way that the funds were targeted affect the ultimate impact of the program? Would a given amount of funding distributed in another way have been more effective? Would future anti-recessionary spending programs benefit from pre-planned allocation formulas? Answering those questions would take more than a blog post.

Disclaimer The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Orr is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

John Sporn is a senior analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comment. The post was not meant either as a critique of the approach or to suggest the policy had little effect. We wanted to describe the allocation framework which was used, and we left it as an open discussion whether such a framework should be used in future stimulus efforts.

While it is interesting to know that the ARRA was not allocated according to state employment rates, that is hardly a valid criticism of that portion of fiscal stimulus as a policy. Ideally, allocations to states would act as a surrogate for the states being able (financially and politically) to borrow so as to carry out activities that have positive NPV when evaluated at the temporarily reduced discount rate and at shadow prices incorporating unemployment of the factors of production used in such activities. I would not expect such an ideal allocation to be highly correlated with unemployment rates of labor across states.