James Narron and David Skeie

As

momentous as financial crises have been in the past century, we sometimes

forget that major financial crises have occurred for centuries—and often. This

new series chronicles mostly forgotten financial crises over the 300 years—from

1620 to 1920—just prior to the Great Depression. Today, we journey back to the

1620s and take a fresh look at an economic crisis caused by the rapid

debasement of coin in the states that made up the Holy Roman Empire.

The Kipper und Wipperzeit (1619–23)

The Kipper und Wipperzeit is the common name

for the economic crisis caused by the rapid debasement of subsidiary, or

small-denomination, coin by Holy Roman Empire states in their efforts to

finance the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). In a 1991

article, Charles Kindleberger—author of the earlier work Manias, Panics and Crashes and

originally a Fed economist—offered a fascinating account of the causes and

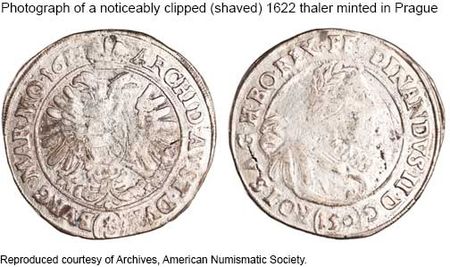

consequences of the 1619–23 crisis. Kipper refers to coin clipping and

Wipperzeit refers to a see-saw (an allusion to the counterbalance scales used

to weigh species coin). Despite the clever name, two forms of debasement actually

fueled the crisis. One involved reducing the value of silver coins by clipping

shavings from them; the other involved melting the coins, mixing them with inferior

metals, re-minting them, and returning them to circulation. As the crisis

evolved, an early example of Gresham’s Law took hold as bad money drove out

good. As Vilar notes in A History of Gold

and Money, once “agriculture laid down the plow” at the peak of the crisis

and farmers turned to coin clipping as a livelihood, devaluation,

hyperinflation, early forms of currency wars, and crude capital controls were

either firmly in place or not far behind.

From Self-Sufficiency to Money and Markets

The period preceding and including the early 1600s was marked by a

fundamental shift from feudalism to capitalism, from medieval to modern times,

and from an economy driven by self-sufficiency to one driven by markets and

money. It is within this social and economic context that various states in the

Holy Roman Empire attempted to finance the Thirty Years’ War by creating new

mints and debasing subsidiary coins, leaving large-denomination gold and silver

coins substantially unaffected.

In a simple example, subsidiary coin

might initially be minted using only silver, then gradually undergo a shift in

metallic content as a growing percentage of copper was added during

re-mintings, until the monetary system was effectively on a copper rather than

a gold or silver standard. This shift in metallic content created a divergence

between a coin’s nominal value and its intrinsic metal value, which led to the

rapid debasement of coin. As Kindleberger notes, “Bad money was taken by

debasing states to their neighbors and exchanged for good [money]. The neighbor

typically defended itself by debasing its own coin.”

Owing to trade and the easy

circumvention of laws that forbade the removal of coin from a city, states

found that early forms of capital controls were ineffective and that a large

portion of circulating coin originated elsewhere. Given this porosity,

individual states determined that reforming their own minted coinage by

returning to a silver standard did not necessarily allow them to reform the

currency circulating within the state. So states sought greater revenue through

seigniorage—the difference

between the cost of production (including the price of the metal contained in

the coin) and the nominal value of the coin—by minting more money

and by taking debased coin abroad, exchanging it, and bringing home good coin and

re-minting it.

The rapid debasement up to 1622

created a European boom, which turned to mania by early 1622 when average

citizens turned to coin clipping as a livelihood, then hyperinflation in 1622

and 1623. Many became rich by exploiting the unknowing—typically peasants. This

ultimately led to a widespread breakdown in trade as peasants, fearing that

they would be paid in debased coin, refused to bring products to market,

creating the spillover to the broader economy.

Cry Up, Cry Down, or Call In

One response to the crisis was for states to “cry up” good coins by raising

the denomination or “cry down” bad coins by lowering their denomination. Another

response was to “call in” coin and re-mint it. A third response was to enforce

minting standards. But central authority was so weak that no one state could

solve the crisis without the help and support of neighboring states. States

were finally able to solve the crisis through mint treaties and by setting

exchange rates, with hyperinflation subdued by a return to the Imperial

Augsburg Ordinance of 1559. Because the public became so wary of clipped and

debased coin, it took months to convince the masses that coin was good once it was

restored.

History Repeating Itself

Like markets and money, crises evolve easily but lessons learned often last

only a lifetime and are easily forgotten. Over the coming year, we’ll share

with you how elements of this crisis were repeated during the Great Re-Coinage

of 1696, the Mississippi Bubble of 1720, the Dutch Commodities Crash of 1763,

and the Continental Currency Crisis of 1779, with each crisis adding a unique

twist.

In the meantime, as we reflect upon

the states’ struggles to manage their domestic economies of the 1620s at a time

of evolving money, markets, and trade, and amid pressure to finance the Thirty

Years’ War, we pose the following question: Is it possible to draw any parallels

between the events of the 1620s and the current objectives of the Group of Seven to meet “respective domestic objectives using

domestic instruments”? Tell us what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Executive Office.

David Skeie is a senior economist in the Bank's Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Fantastic! Please continue. The more obscure the crisis, the better. But why limit yourselves to Europe? China for instance had paper currency for far longer than anyone else; there have to be some interesting crises in China’s monetary history.

“…crises evolve easily but lessons learned often last only a lifetime and are easily forgotten.” So true! We rarely talk about lessons learned prior to the Great Depression. Very educational and fun facts about currency manipulation in the earlier days. Confucius said “Understanding the present by reviewing the Past.” I look forward to seeing your next blog.

I also look forward to the series. The Kindelberger quote: Bad money was taken by debasing states to their neighbors and exchanged for good [money]. The neighbor typically defended itself by debasing its own coin. describes a specie-based version of competitive devaluation. Wikipedia: Currency war, also known as competitive devaluation, is a condition in international affairs where countries compete against each other to achieve a relatively low exchange rate for their own currency. I think it important to note that while Wipperzeit follows from debasement as government policy, Kipper does not.

Dear Sirs: The most noticeable parallel to me – between the events of the 1620s and the current objectives of the Group of Seven – is how domestic instruments, or policies, can lead to speculation affecting the value of money. Market determined exchange rates for money have always shown themselves prone to speculation through such domestic policies (e.g., tariffs, bimetallism, other commodity standards and instruments), as explained so brilliantly not only by Kindleberger but also by John Chown. See: Chown, “A History of Money: From AD 800” http://pinterest.com/pin/45247171226609588/ Sincerely, Ronald Grey http://RonaldGrey.com/JoinMe

I am looking forward to your further exploration of historic crises. Yes, I would agree there are some similarities between debasing coins via ‘clipping’ and using ‘domestic instruments’ such as sovereign bond purchases to repress interest rates. What disturbs me the most about these similarities is that the current global market environment is far more complex; as we experienced in 2008, the consequences of any government policy missteps can be far more severe than any expected.