M. Henry Linder, Richard Peach, and Robert W. Rich

Among the measures of core inflation used to monitor the inflation outlook, the series excluding food and energy prices is probably the best known and most closely followed by policymakers and the public. While the conventional “ex food and energy” measure is a composite of the price changes of a large number of different products and services, almost all models developed to explain and forecast its behavior do not distinguish between the goods and services categories. Is the distinction important? Here, we highlight the different behavior and determinants of goods inflation and services inflation and suggest, based on preliminary analysis, that we can improve the forecast accuracy of this conventional core inflation measure by combining separate inflation forecasts of the two categories.

Every Picture Tells a Story (Don’t It?)

As specified in the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, the Federal Reserve’s mandate is “to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Given long and variable lags between changes in monetary policy and the subsequent impact on the economy, meeting these goals is greatly facilitated by being able to accurately forecast the behavior of inflation over a one-to-two-year horizon. This, of course, is easier said than done, as headline inflation measures, such as Consumer Price Index (CPI), tend to be quite volatile, due in large part to sharp swings in energy and food prices.

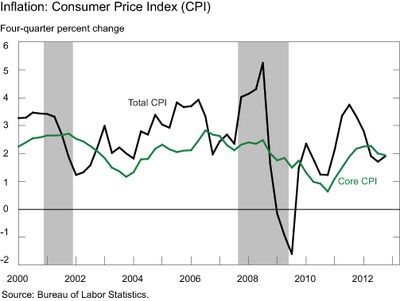

Because of the volatility in headline inflation, policymakers have relied on core inflation measures designed to differentiate between transitory and persistent price changes to help guide their decision making. Among the measures of core inflation, the “ex food and energy” series has been the most widely adopted for this purpose (see this paper by Timothy Cogley for a discussion of other core inflation measures). This measure, shown in the chart below, is a much less volatile series that is indicative of lower-frequency changes of the general price level and has also proved to be a more accurate predictor of headline inflation than past headline inflation.

However, models developed to explain and forecast core inflation—such as Phillips curve models—do not have a particularly good track record, to the point that there is disagreement regarding the fundamental determinants of inflation.

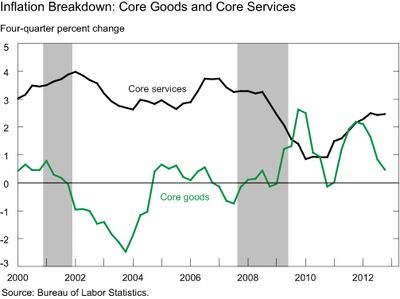

One possible explanation for this state of affairs is that core inflation is a composite of the price changes of a large number of different products and services that behave quite differently over time. The next chart presents core inflation at one level of disaggregation—commodities less food and energy commodities (or core goods) and services less energy services (or core services). Note that the absolute level of inflation of these two categories is quite different as are their weights in the core CPI; the weight of core goods was 34 percent in 1985, but was just 26.1 percent in 2012. Additionally, over the past decade, the two inflation rates have generally moved inversely to each other.

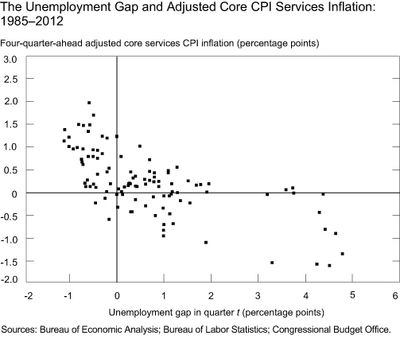

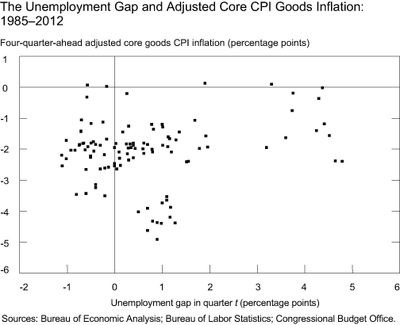

It seems likely that the divergence in the behavior of goods inflation and services inflation may also carry over to their determinants. To explore this idea, we examine the relationship over the period since 1985 between each inflation series in the previous chart and two variables considered to be important in predicting inflation: long-run inflation expectations and the level of domestic resource utilization. Resource utilization provides a gauge of the balance between aggregate demand and supply in an economy. One of the most widely used measures of domestic resource utilization is the unemployment gap—the difference between the unemployment rate and the estimate of the time-varying Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The next two charts present scatter plots of the four-quarter-ahead inflation rates (period t to t+4) of core services and core goods, respectively, less a measure of ten-year expected CPI inflation (period t) from the U.S. Survey of Professional Forecasters, versus the CBO unemployment gap (period t). For core services, there is a nonlinear, negative relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment gap. For core goods, however, no such relationship is present.

What Explains Movements in Services Inflation and Goods Inflation?

Based on the three charts above, the behavior and determinants of core services inflation and core goods inflation differ significantly. Can we say more about this? To do so, we have developed and estimated separate models for core CPI services inflation and core CPI goods inflation using quarterly data from 1986:Q1 to 2012:Q4. We can provide the following summary of the results.

The core services inflation model draws upon the modeling approach outlined in this Federal Reserve Bank of Boston paper by Jeffrey Fuhrer, Giovanni Olivei, and Geoffrey Tootell. We find a strong relationship (both economically and statistically speaking) between core services inflation and long-term inflation expectations. There is also an important nonlinear relationship between core services inflation and the unemployment gap, indicating that the impact of changes in labor market slack on core services inflation depends on the level of slack itself.

For the core goods inflation model, the results suggest a very different set of factors influencing the behavior of the series. We find persistence in the series, that is, core goods inflation depends on its own past value. Relative import price inflation—growth in (non-petroleum) import prices less core goods inflation—also matters, suggesting goods prices act as the linkage between supply shocks and core inflation. There is also evidence of a relationship between core goods inflation and expected inflation, but that the relevant inflation expectations are associated with a short-term (one-year) horizon. Last, we find no meaningful effect of the unemployment gap on core goods inflation, consistent with commentators who contend that it is global (and not domestic) economic slack that impacts core goods inflation.

The Whole versus the Sum of the Parts

Taken together, the evidence supports the view that the behavior and determinants of core services and core goods inflation are quite different. Why might this matter? Based on some preliminary work, there appear to be gains in the forecast accuracy of aggregate core inflation from using separate models for core services inflation and core goods.

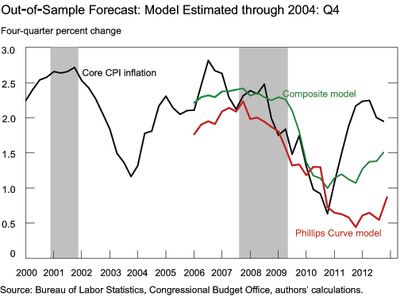

The estimated models can be used to generate forecasts of core services inflation and core goods inflation, which can then be combined using the relative weights of each category in the core CPI. To provide a basis of comparison, we also produce forecasts from an estimated Phillips curve model of aggregate core CPI inflation that uses long-term inflation expectations, the unemployment gap, and relative import price inflation as explanatory variables.

We estimate the models from 1985:Q1 to 2004:Q4, and then forecast out-of-sample for the post-2004 Q4 period. To construct forecasts of the “composite model,” we use weights of 28 percent for core goods and 72 percent for core services—the relative weights in the core CPI in 2004. As shown above, the forecasts from the composite model capturing the differences in the determinants of the inflation process of core goods and core services are over 65 percent more accurate than the forecasts from the Phillips curve model ignoring those differences. While both models generally track the slowing in core inflation during the recent recession, the forecasts from the composite model have done a better job picking up the subsequent rebound in core inflation. Although they are not shown, we obtain similar results based on the post‑2007 Q4 period.

While we recognize our analysis is preliminary, the results suggest that a further exploration of core services inflation and core goods inflation and their role in the core inflation process is warranted.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

M. Henry Linder is a research associate in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

M. Henry Linder is a research associate in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Richard Peach is a senior vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Richard Peach is a senior vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Robert W. Rich is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Robert W. Rich is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

For readers who are interested, I have done a little research with respect to components price behavior going back as far as I can find reliable data. (http://seekingalpha.com/article/1241821-inflation-and-yields-the-evolution-of-gibson-s-paradox-and-the-revolution-in-prices-part-v) The divergence in technological goods vs services vs commodities appears to have begun with the establishment of the Fed and really intensified after World War II. This coincides with the breakdown in the old formulation of Gibson’s Paradox. And, it largely coincides with a strange, post-War relationship between yields and CPI that can be expressed as: EY – DY + 10yr – 1yr – CPI% = 0, where EY and DY stand for the S&P’s earnings and dividend yields and 10yr and 1yr for long and short-term rates. Interestingly, the relationship between primary commodity prices (when adjusted for inflation after the establishment of the Fed) and equity yields appears to be unchanged, presumably over the last 280 years (and which I believe is, therefore, a more precise rendering of Gibson’s Paradox).

I worry that the time horizon that this study looks at might be too short. Can you take it back prior to the big run up in commodities prices that started around 2000?

Nice work. It might be interesting to check core goods inflation against import prices and/or the dollar index. I’ve found discrepancies between forecast and actual inflation rates are related to the value of the dollar. Since manufactured goods are often tradeable, this could be affecting the relationship for goods inflation.