Jason Bram and Jonathan Hastings

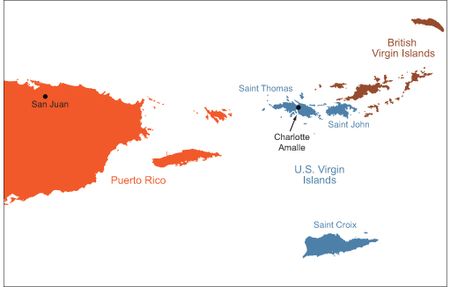

The U.S. Virgin Islands are a small and unique component of the Second Federal Reserve District. Situated just east of Puerto Rico, the islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John are home to roughly 106,000 residents—less than one-thirtieth of Puerto Rico’s population—and make up a territory of the United States. Yet the U.S. Virgin Islands are often ranked as the Caribbean’s top vacation destination on U.S. soil. In this post, we briefly describe the structure of the local economy and look at trends and developments over the years—especially the past few years, during which the islands lost a major employer and endured a prolonged and wrenching economic downturn . . . that now appears to be bottoming out.

A Profile of the U.S. Virgin Islands’ Economy

Before we get to how the local economy is doing, let’s give a quick profile of what comprises and what drives it. Not surprisingly, tourism is a major industry sector on these tropical islands: Leisure and hospitality accounts for roughly 18 percent of employment—nearly double its share on the mainland—and retail trade represents another 15 percent, also above the mainland average. The territorial government (analogous to state and local government) is also a major employer: It represents more than 25 percent of jobs—a much higher proportion than state and local jobs on the mainland. Until recently, oil refining had been a major industry; now, the most prevalent manufacture of the islands is rum.

How about its population and labor force? Just under 20 percent of adults (twenty-five and over) hold a college degree—below the 28 percent mainland average and a somewhat lower share than on nearby Puerto Rico. The University of the Virgin Islands is the sole accredited institution of higher education, with campuses on St. Croix and St. Thomas.

However, the Virgin Islands contrast with Puerto Rico on some dimensions. First, based on the 2010 census, a relatively high share of the adult population (sixteen and older) is in the labor force: 66 percent, versus 65 percent on the mainland and well below 50 percent in Puerto Rico. Also, fewer than half of all homes are owner occupied, compared with 65 percent on the mainland and well over 70 percent in Puerto Rico.

Economic History of the U.S. Virgin Islands

Recall that tourism has historically been a major industry of the islands—both as a major stop-off for cruise liners and as a tropical destination itself. In 1966, a major oil refinery opened on St. Croix; by 1974, its capacity had been expanded, making it one of the world’s top oil refineries until recently (more on this in a moment). Watch manufacturing also used to be a major export industry here.

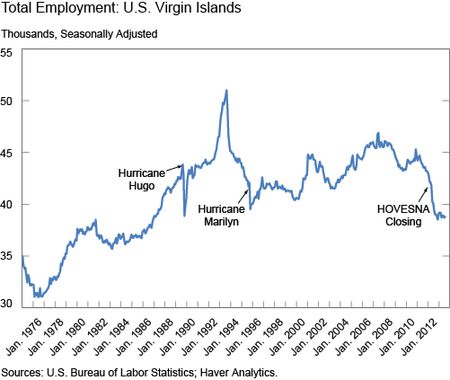

More broadly, the 1960s and 1970s marked an era of robust growth in the Virgin Islands: Between 1960 and 1980, the population more than tripled, from 32,000 to almost 97,000. Population continued to grow modestly in the 1980s, while job growth remained fairly robust. By the early 1990s, employment reached an all-time high of roughly 50,000, partly as a result of a major construction project at HOVENSA, the Islands’ largest private employer at the time. By 2000, population reached 109,000—an all-time high for census years. However, employment didn’t grow during the 1990s or during the past decade (see chart below).

Historically, one of the most troublesome characteristics of this tropical location has been its vulnerability to hurricanes. Since the late 1980s, the U.S. Virgin Islands have been hit with a number of them; but none more severe than Hugo in September 1989. That storm destroyed much of the infrastructure of St. Croix and St. Thomas; it also led to a roughly 10 percent drop in employment across the islands in October—a loss that would take another four to six months to fully reverse. Another major shock to the region came in the form of Hurricane Marilyn in September 1995. While not as severe as Hugo, it led to a roughly 2½ percent drop in local employment, which again was fully reversed within six months. But the U.S. Virgin Islands’ most recent economic shock was not weather related.

Signs of Recovery after the Latest Economic Shock

Unlike Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands didn’t go into recession until late 2007—right along with the U.S. mainland. Similarly, the islands’ economy started showing signs of recovery in late 2009. By late 2010, the outlook was looking promising: The local economy had recouped about half of the net job loss during the recession and a major rum manufacturer relocated its distillery from Puerto Rico to St. Croix. Real GDP, which had tumbled 5½ percent in 2009, rebounded by nearly 2 percent in 2010. In 2011, however, GDP fell another 6.6 percent, while gross domestic income and employment declined much more modestly.

Then, in early 2012, the HOVENSA oil refinery, the islands’ largest private sector employer, shut down with little advance notice—quite a shock to the local economy. By May 2012, manufacturing employment had plunged by nearly 50 percent and total employment had fallen by more than 6 percent, or 2,600 net jobs. By November 2012, employment had fallen by another 4 percent (1,700 jobs). Moreover, the manufacturing jobs were exceptionally high paying, and the output was largely exported. For 2012 overall, GDP fell by a stunning 13 percent, mainly reflecting a nearly 80 percent drop-off in exports (mostly refined petroleum).

Since last November, however, private sector employment overall has begun to recover modestly. While manufacturing sector employment has remained moribund, there’s been some pick-up in leisure and hospitality jobs—a reassuring sign, given that this sector is a mainstay of the local economy and brings in revenue from outside. There’s also been moderate job creation in the “other services” category (such as personal care and business associations). These two sectors together account for just about all of the 600 net private sector jobs created since last November. Part of this, though, has been offset by job cuts in government.

Looking ahead, we note that the tropical weather and picturesque beaches will continue to draw tourists, and natural resources bode well for rum production. But it may also be worthwhile to look at the physical infrastructure and human capital built up over the years, with an eye toward using it for other types of productive economic activity.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jason Bram is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jonathan Hastings is a financial/economic analyst in the Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

“…Historically, one of the most troublesome characteristics of this tropical location has been its vulnerability to hurricanes. Since the late 1980s, the U.S. Virgin Islands have been hit with a number of them; but none more severe than Hugo in September 1989…” Yes. Hugo was devastating. But it was the first hurricane to hit the USVI in at least 20 years (I moved there isn 1968) and, as i recall, for a decade or two before that. So two hurricanes in 45 years, perhaps longer. How does that rise to “the most troublesome characteristics of this tropical location”?