James Narron, David R. Skeie, and Donald P. Morgan

With intermittent war raging across much of Western Europe near the end of the eighteenth century, by about 1795, Hamburg had replaced Amsterdam as an important hub for commodities trade. And from 1795 to 1799, Hamburg boomed. Prices for goods increased, the harbor was full, and warehouses were bulging. But when a harsh winter iced over the harbor, excess demand and speculation drove up prices. By spring, demand proved lower than supply, and prices started falling, credit tightened, and the decline in prices accelerated. So when a ship bound for Hamburg laden with gold sunk off the coast, an act meant to avert a crisis failed to do so. In this issue of Crisis Chronicles, we use some diverse sources from the American Machinist and Mary Lindemann’s Patriots and Paupers to explore the Hamburg crisis of 1799 and describe how harsh winter weather still impacts the economy today.

Hamburg Booms and Busts

The occupation of Holland by France in 1795 triggered a sudden shift in the continental trade from Amsterdam to Hamburg. So as commodities flowed from the Americas and West Indies, Hamburg served as the new gateway to Europe. But the sudden shift of activity to Hamburg was accompanied by speculation, a rise in prices, and an expansion of credit. Cheap housing was replaced with warehouses, rents increased, and merchants reaped the profits from a war-torn Europe. But the summer of 1798 was dry, and the autumn wheat harvest was poor. And the winter of 1798-99 was one of harshest on record, setting in early, immobilizing ships, and hampering the transfer of goods from ship to shore.

As speculation further drove up prices, consumption decreased, and by spring, supply greatly outstripped demand and prices fell. Bills of exchange, which had previously expanded, now contracted, sales fell, and prices plummeted. By August 1799, the crisis had begun in earnest with Hamburg in the grips of a violent commercial contraction.

Sinking of the HMS Lutine Furthers Financial Crisis

In response to the severe liquidity strains, England agreed to ship about 1.2 million pounds in specie to Hamburg aboard the frigate HMS Lutine to help avert the crisis. But on October 9, 1799, the Lutine sank in a gale off the coast of Holland, leaving just one survivor. The seas were so rough in the following weeks and months that the specie coin could not be recovered, and the crisis continued unabated. Between August and November, eighty-two banking houses failed and more than 150 firms were declared insolvent, with the crisis spreading to other trade centers like Bremen and Frankfurt. While the crisis was shocking in the short term, there were few lasting problems.

The Lutine’s cargo was insured by Lloyd’s of London, and while Lloyd’s found some of the Lutine’s gold and its bell in the 1850s, the bulk of the treasure still lies buried off the coast. Today, the Lutine’s bell can be found at Lloyd’s headquarters in London, where it is occasionally used for ceremonial purposes.

Extreme Winter Weather Causes Widespread Disruption for U.S. Economy

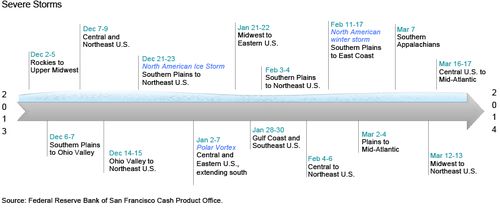

In April, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated 2014:Q1 GDP growth of 0.1 percent, then later revised that estimate to a nearly 3 percent contraction, down from an increase of 2.6 percent in the previous quarter. But rather than signaling a persistent downturn in the U.S. economy, most economists expect the decline to be transitory and attribute it to the extreme winter weather that blanketed much of the country from early December to mid-March. This was the first contraction of the U.S. economy since 2011:Q1, but the contraction was more severe than the last. Corporate profits fell almost 15 percent, and exports fell nearly 10 percent.

Contending with storms such as the polar vortex that struck much of the eastern half of the country in early January 2014, many factories in the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast were closed, transportation links were frozen, and inventories were decreased.

But severe winter weather is only part of the story. Some estimates put the impact of the winter weather at about 1.5 percent of the 2.9 percent contraction. San Francisco Fed Research Advisor Rob Valletta notes in a Fed Views article that the decline may be transitory. But while some of the remaining factors, such as consumer spending, have rebounded, the housing recovery remains a concern. Our colleagues at the Cleveland Fed have conducted research that suggests that, in addition to the increase in mortgage rates and some tightening of lending standards, the severe winter weather affected residential investment as well. They also suggest that a return to normal weather should allow for some rebound in residential investment.

So the next time harsh winter weather sets in, whether it’s in Hamburg or Pittsburgh, remember that it might impact the local or regional economy. But tell us what you think. How much are the winter storms to blame for the contraction in the first quarter? As 2014:Q2 GDP growth estimates are also being revised somewhat downward recently, is the underlying economy lagging or are we rebounding from the harsh winter weather?

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president and cash product manager at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

At the time this post was written, David R. Skeie was a senior financial economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group. He is now an assistant professor of finance at Mays Business School, Texas A&M University.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics