Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz

This post is the second in a series of four Liberty Street Economics posts examining the value

of a college degree.

In yesterday’s blog post and in our recent article in the New York Fed’s Current Issues series, we showed that the economic benefits of a bachelor’s degree still outweigh the costs, on average, even in today’s difficult labor market. Like others who assess the value of a bachelor’s degree, we base our estimates on the assumption that a student takes four years to finish the degree. But it is not uncommon for people to take longer than that. In fact, recent data indicate that among those who complete a bachelor’s degree within six years, only about two-thirds finish in four years or less. What does it cost to stay in college for a fifth or sixth year before finishing that degree? Perhaps more than you might think.

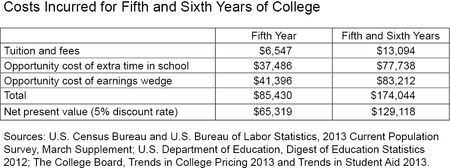

How should we measure the costs of taking an extra year or two to complete a bachelor’s degree? The most obvious cost is the extra tuition and fees that must be paid (room and board are not really an extra cost from an economic perspective, since they have to be purchased regardless of whether one is in school). In our recent article, we showed that the average net tuition cost—which reflects what the average student actually pays out-of-pocket when various forms of aid and tax benefits are taken into account—is a little more than $6,500 per year. However, in economic terms, tuition is only a small part of the extra costs incurred for that fifth or sixth year of school. There are also opportunity costs to consider, and these add up in ways that may not be obvious at first glance.

First, students who spend an extra one or two years in school as a full-time student incur an opportunity cost in the form of forgone earnings. Economists measure this cost as the wages one could have earned with a college degree had one graduated a year or two earlier. Second, entering the job market a year or two late damages students’ lifetime earnings profile. In addition to giving up one or two years of college-level earnings while in school, students miss out on a year or two of experience and the extra push that gives their wages over their working life.

While we don’t directly observe people who graduate in five or six years, we can use our analytical framework to simulate what the added costs would amount to, based on the average wages of college graduates in general. Using our estimates, we determine that someone who finishes a bachelor’s degree in four years would earn, on average, about $37,500 their first year on the job. By the time that person reaches the age of twenty-five, they earn an average of about $45,500, having racked up a few years of experience and commensurate raises. If we assume that a five- or six-year graduate follows the same earnings path but starts working a year or two later, we find that a five-year graduate would earn $43,000 at the age of twenty-five ($2,500 less than a peer who graduated in four years), and a six-year graduate would earn only about $40,000 ($5,500 less). This earnings “wedge” persists throughout one’s career. The differences add up each and every year, so that those graduating later never really catch up to those who graduated earlier.

In the table below, we use the 2013 lifetime earnings profiles from our article to estimate the costs of taking an additional year or two to complete the bachelor’s degree. All in all, an extra year of staying in school costs more than $85,000, and for those who take two extra years to finish, it costs about $174,000. The net present value of these totals, using a 5 percent discount rate, yields a cost of about $65,000 for each additional year spent in school.

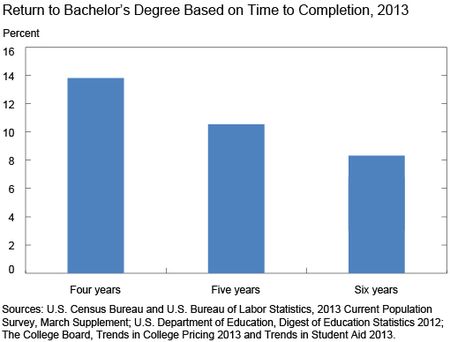

Alternatively, we can look at how the return to a bachelor’s degree declines as time to completion increases, as shown in the chart below. Using 2013 data, we estimate that the rate of return for the average student who finishes the degree in four years is about 14 percent. That figure gets shaved down to about 11 percent for a five-year completion, and to 8 percent for six years. Overall, the rate of return plummets by 40 percent for the six-year plan compared with the traditional four-year plan.

The upshot of our discussion? For students who require five or six years to graduate, the value of a bachelor’s degree no doubt remains substantial, but staying on in college certainly takes a financial toll.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I read with interest your recent article and appreciate the research behind it. Perhaps you would consider publishing the results for a graduate who earns a bachelor’s degree, but chooses at some point to step out of the workforce to raise a family – 6 years, 16 years? – then re-enters.

Presumably at every point in the college career there’s a risk of dropping out. How many college dropouts are there compared to the people who finish in 4 years or 6? Can you estimate the return to spending time in college without earning a degree? At what point might the expected net return to an additional year become negative?