Ever since the first census of the U.S. population was taken, back in 1790, New York City has been the nation’s largest city, and for most of this time by a factor of more than two. But how has the city—in particular, the city’s boundaries—evolved over time?

In the latter part of the 1800s, New York City comprised the island of Manhattan and a small but expanding portion of what is now the Bronx. It was only after the 1898 consolidation that the city became the five boroughs that delineate it today. Yet today, as then, Manhattan is widely considered the core of the city’s economy: it has triple the population density of the rest of the city, more jobs than the other four boroughs combined, a disproportionate share of high-paying jobs, most of the city’s hotel rooms, the highest land values, and so on. Even many residents of Queens, Brooklyn, and the other boroughs colloquially refer to Manhattan as “the city.”

The Increasingly Vibrant Boroughs

Nevertheless, while Manhattan remains the city’s primary economic engine, something has been happening over the past few decades that is often overlooked: the other boroughs have been outpacing Manhattan in growth—in terms of population, and especially of employment and economic activity. Moreover, this shift has occurred during a period of generally robust growth for the city overall.

To some extent, the “outer boroughs” have historically been thought of as “bedroom communities” for Manhattan—that is, many residents commute out (largely to Manhattan) for work, but far fewer commute in. Yet, while there is certainly a substantial net flow of commuters into Manhattan, the other boroughs have a strong and expanding job base, along with some important industry clusters. Take the Bronx, for instance: the health care industry accounts for roughly 87,000 jobs, or more than 35 percent of borough-wide employment, and even a slightly higher share of all wage and salary income. Moreover, hospitals in the Bronx have expanded employment by 25 percent since 2006, while hospital employment across the rest of the city has remained essentially unchanged. Other industry clusters in the outer boroughs—smaller but still noteworthy–include air transportation in Queens (anchored by two major airports), water transportation in Staten Island, and apparel in Brooklyn.

Recent Trends across the City

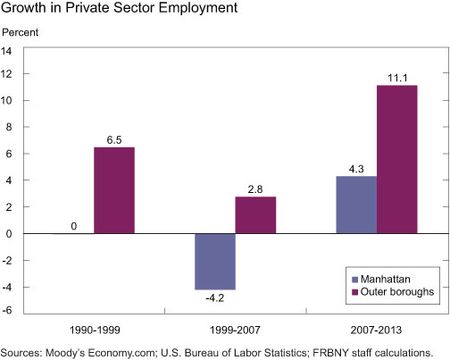

But how have these boroughs’ economies as a whole performed, relative to Manhattan’s, over time? From 1999 to 2007—the years leading up to the Great Recession—employment grew 3 percent in the outer boroughs, while it declined by 4 percent in Manhattan (see chart below).

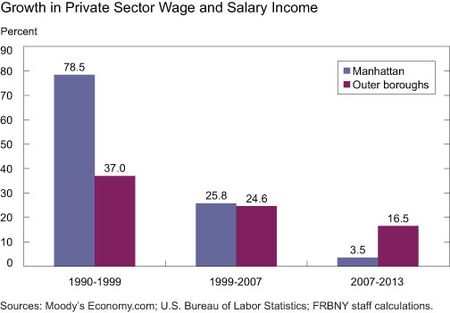

Differences in employment growth were similar during the 1990s. In terms of income growth, however, Manhattan outperformed the outer boroughs—largely because Manhattan had seen extraordinary earnings growth during economic booms, driven by Wall Street. So even though Manhattan lagged in job creation, wages and salaries in the borough’s securities industry grew rapidly. Moreover, this high-paying industry, until the early 2000s, had been growing as a share of total employment, “upscaling” the mix of jobs and fueling income growth in Manhattan.

In more recent years, however, the outer boroughs have gained on Manhattan in both employment and income growth. From 2007—right before the last recession—to 2013 (the latest data available), private-sector employment grew by a little more than 4 percent in Manhattan, compared with 11 percent in the other boroughs overall. Much of this discrepancy reflects the fact that job losses during the downturn were much steeper in Manhattan than in the rest of the city. In particular, Brooklyn and the Bronx saw almost no net job loss during the downturn; over the last six years, these two boroughs saw job gains of 16 percent and 12 percent, respectively. Queens registered 8 percent job growth, while job gains in Staten Island were roughly on par with those in Manhattan. As for growth in total private sector wage and salary income, since 2007, income has grown nearly four times as fast outside as inside Manhattan—specifically, by 16½ percent as compared with 3½ percent (see chart below). This pattern contrasts markedly with previous recession-recovery periods, when (as noted earlier) Manhattan would typically lead the city in income growth, driven by Wall Street.

A Virtuous Cycle

Looking back at the past couple of decades, it would seem that the outer boroughs’ stellar performance has coincided with an era of robust growth for the city’s economy overall. So is this blossoming of the city’s economy outside Manhattan more an outcome or a cause of the city’s long-standing economic boom? Well, probably some of both. Clearly, rising demand to live and do business in the city has pushed up land values, real estate prices, and rents (both commercial and residential), making the less pricey neighborhoods in places like the Bronx and Brooklyn more and more appealing. At the same time, the growing appeal and viability of the outer boroughs have likely been a major factor enabling the city’s economic capacity to grow faster than it could have in Manhattan alone. In effect, the city’s central business district has expanded outward—and not only to the east but also to the Gold Coast of New Jersey and beyond. It should be noted that a key feature permitting the geographic expansion of this massive urban economic engine is the extraordinary mass transit infrastructure that enables millions of people to move around efficiently and relatively cheaply.

Finally, we would be remiss if we wrapped up without acknowledging some of the struggles and policy challenges that are partly associated with the city’s economic boom, such as housing affordability, income inequality, gentrification, and business costs. These are issues that warrant more attention and that we will address in future blog posts. Still, New York City’s expanding economy and tax base certainly provide many resources for local governments and other local organizations to alleviate some of these problems—an advantage not available to many struggling urban economies across the nation and around the world.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Jason Bram is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics