In the first of this two post series, we investigated the relationship between state aid and local funding before and after the Great Recession. We presented robust evidence that sharp changes in state aid brought about by the prolonged downturn influenced local budget decision-making. More specifically, we found that relative to the pre-recession relationship, a dollar decline in state aid resulted in a $0.19 increase in local revenue and a $0.14 increase in property tax revenue in New York school districts. In this post, we dive deeper to consider whether there were variations in this compensatory response across school districts, using an approach described in our recent study. For example, one might expect that there would be differences in willingness and ability to offset cuts in state aid across districts with varying levels of property wealth, which in turn might lead to differences in responses. Was this really the case?

Districts with higher property wealth contain more wealthy families and we might expect wealthier families to have a higher demand for education. If so, wealthy districts will have a higher propensity to counter any state aid cuts. Additionally, these districts are likely to be better able to compensate for cuts in state aid, relative to low-value property districts, by virtue of their larger property tax bases. Another important factor that is likely to contribute to differences across such districts is the School Tax Relief Program (STAR). Instituted in New York in 1997, STAR is a homestead tax exemption program aimed at reducing homeowners’ property taxes by providing a state subsidy that pays for a portion of homeowners’ school district property taxes. Existing analysis of STAR points to increased property tax rates and educational spending as a result of the subsidy. In addition, evidence suggests that STAR’s benefits tend to go primarily to wealthier districts, that is, those with more homeowners and higher property values. This disparity is largely due to the “sales price differential factor,” which is used to scale up the STAR benefit in counties where the median home sales price exceeds the statewide median sales price (in other words, high property value districts). As a result, STAR may offset increases in property tax proportionally more in wealthy districts than in poor districts, making it more likely that wealthier districts would raise property tax revenue when faced with declining state aid.

To explore any such variation in responses, we divide districts into quartiles based on their per pupil property values in the pre-recession period. For each quartile, we investigate whether a decline in state aid per pupil in the post-recession period led to any offsets by local (and property) tax revenue (relative to the pre-recession relationship). Doing so allows us to see if these responses varied across the various quartiles. Availability of a long panel of data allows us to control for pre-recession trends and investigate whether the responses varied across the various post-recession years. Because of the richness of our data, we are also able to control for a wide range of time-varying demographic, socioeconomic, and financial attributes of districts in addition to time-invariant characteristics of the districts.

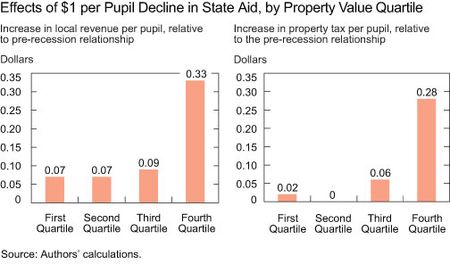

The chart below presents our main findings graphically. In both panels, the bars represent the amount that a one dollar decline in state aid per pupil is offset by local (or property tax) revenue in the post-recession period (relative to the pre-recession relationship) for each of the property value quartiles. For example, the right-most bar implies that a dollar decline in state aid per pupil in the post-recession period led the districts in the top (fourth) quartile to increase local revenue per pupil by $0.33 and property tax revenue by $0.28, relative to the response in the pre-recession period. The largest compensatory response in the post-recession period took place in the fourth quartile, among the districts richest in property wealth. We see a qualitatively similar, but economically smaller, compensatory response in the third quartile. For each dollar decline in state aid per pupil, the districts in the third quartile responded by increasing local revenue by $0.09 and property tax revenue by $0.06, relative to the pre-recession relationship. All effects in the third and fourth quartiles are statistically different from zero. The corresponding (relative) offsets in the first and second quartiles, though they carry the same sign as those in higher quartiles, are often not statistically significant. For the first quartile, relative offsets were $0.07 and $0.02 for local and property tax revenue per pupil, respectively; the latter effect is not statistically significant. The effects for the second quartile are never statistically significant, and also economically quite small.

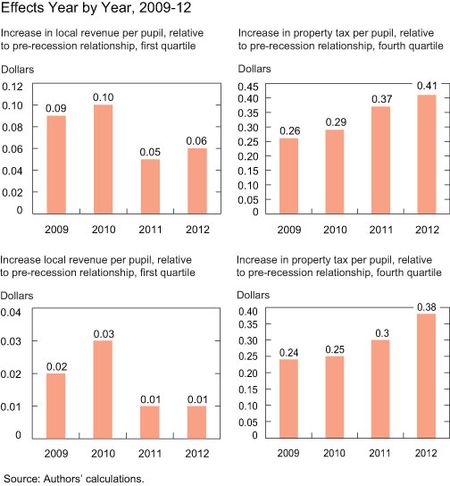

To assess whether these effects were caused by responses in a single stray year, we split the post-recession period into its individual years and study the responses in each of those years. We observe sustained offsetting over the post-recession years across most quartiles (relative to the pre-recession relationship). The chart below shows results for the first and fourth quartiles. (Information for the other two quartiles is not reported due to space constraints, but is available here.) The findings are statistically and economically strongest in the fourth quartile, where we see consistent and large offsetting. All effects, with the exception of property tax revenue offsetting in the first quartile, are statistically significant.

Exploring these patterns further, we split the data by quartiles of STAR revenue share. (This step is accomplished by calculating the ratio of STAR revenue to state aid in the pre-recession period and classifying districts into quartiles.) It’s expected that districts that relied more heavily on STAR revenue would be more likely to offset cuts in state aid, since it came at a lower cost to them. Furthermore, because wealthier districts tend to rely more heavily on STAR revenue, we expect to see results similar to those above in the property value analysis. Here, we see the strongest post-recession offsetting response (relative to the relationship in the pre-recession period) occurred in the top quartile, with no statistically significant offsetting occurring in the lowest quartile. Between quartiles, the relationship drops off only moderately. For each dollar decline in state aid per pupil, local revenue per pupil was increased $0.34 in the fourth quartile, $0.24 in the third quartile and $0.25 in the second quartile (relative to the response in the pre-recession period). All relationships persist through the individual post-recession years. (To see these trends illustrated in charts, refer to our underlying study.)

Consistent with the results of our earlier post, we find that school districts responded to drastic state aid cuts in the post-recession period by relative offsets through property tax and local revenue

(in comparison to the pre-recession relationship). We go further in showing that the relationship varied perceptibly by property wealth of districts and by dependence on STAR. Wealthier and more STAR-dependent districts raised greater funds through local and property tax revenue in response to cuts in state aid (relative to their pre-recession relationship), likely due to their larger funding sources and willingness to subsidize education. Looking at both property value and STAR quartiles, we observed the weakest relative offsetting effect in the lowest quartile and the strongest effect in the top quartile. This observation implies that poor school districts are likely to be less resilient than wealthier school districts when faced with declines in state aid. It is also an important finding for policymakers to consider, especially when they are allocating government aid among school districts. In fact, if the differential in offsetting we’ve documented above is not accounted for, policy choices could inadvertently exacerbate inequality.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Ravi Bhalla is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics