Today, we are releasing new data on consumers’ experiences and expectations regarding credit demand. We’ve been collecting these data every four months since mid-2013, as part of our Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE). Other data sources describing consumer credit either provide aggregates that are an interaction of credit supply and demand (such as the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel), or show only short-term changes in supply and demand (as reported by the supply side in the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey), or are too infrequent to provide a real-time picture of changes in consumer credit demand and access (Survey of Consumer Finances). The goal of the SCE Credit Access Survey—which will henceforth be published every four months—is to fill this void. In this blog post, we provide an overview of the survey and highlight some of its features.

Survey Overview

We first ask survey panelists about their experiences with credit applications over the past twelve months. Panelists are divided into two groups based on whether they’ve applied for any credit during that period. Those who did not apply are asked whether they had no need for credit, or whether they didn’t apply for credit despite needing it because they believed they wouldn’t be approved; the latter group reflects latent demand for credit. Those who applied for credit, on the other hand, are asked whether their request was granted. We collect this information for seven specific credit products: auto loans, credit cards, credit card limit increases, purchase mortgages, mortgage refinancing, student loans, and increases in limits of other existing loans. On the release page, we present overall application rates and rejection rates for all seven categories combined, as well as by each of the first five credit products (sample sizes are too small for the last two—student loans and increases in limits of other loans). We also collect data on whether respondents had experienced a voluntary or involuntary account closure in the past twelve months.

The second part of the survey collects data from respondents regarding their expectations of applying for credit over the next twelve months and their perceived likelihood that the applications will be accepted; we have been collecting these data since early this year. As in the case of experiences, we ask these questions for each of the seven credit types, and in the release we present overall statistics as well as statistics by product category (for the five credit types).

One interesting feature of our published results is that readers will be able to view statistics not only for the overall sample, but also by age and by respondents’ self-reported credit score; this breakdown is, however, not presented in instances with small sample sizes. For both age and credit score, we divide the sample into three subsamples. In any given cross section, nearly a third of respondents do not report a credit score range, and hence they are assigned to the missing group and are omitted from the credit score subgroup statistics.

Note that the SCE is a rotating panel, so some of the respondents in adjacent cross sections of the Credit Access Survey, fielded every four months, will be different; however, we use weights to ensure that the statistics reported for each cross section remain representative of the population of U.S. household heads.

In the rest of this post, we present select findings from the survey. Interested readers can view additional charts on the release webpage.

Overall Credit Experiences

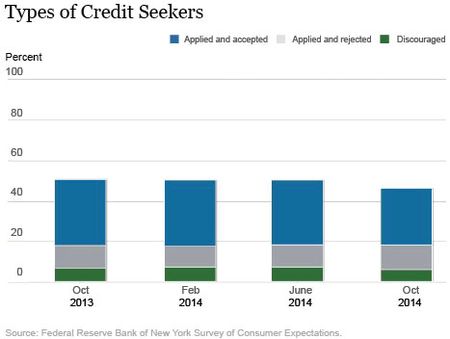

We classify our respondents into four groups, based on their credit experiences: “accepted applicants,” who report being approved for all types of credit that they applied for in the past twelve months; “rejected applicants,” who report applying for some type of credit and being rejected; “discouraged credit seekers,” who report not applying for credit over the past twelve months despite needing it because they believed they wouldn’t be approved; and “nonborrowers,” the group composed of respondents who didn’t apply for credit for other reasons. The figure below shows how the composition of credit seekers has changed since October 2013 (nonborrowers are excluded from the figure). Over the course of the four surveys, the share of discouraged credit seekers has remained steady at around 7 percent, while that of rejected applicants has remained steady at around 11 percent. The share of accepted applicants, having remained steady at around 33 percent for most of the year, dropped to 28 percent in the most recent survey. As a result, the rejection rate—the share of rejected applicants in the pool of (rejected and accepted) applicants—increased to 30 percent in October 2014, up from 25 percent in the previous three surveys.

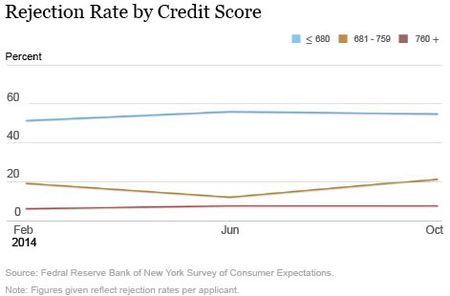

These patterns mask interesting heterogeneity in the data. The figure below shows trends in rejection rates by respondents’ self-reported credit scores; the series starts in February 2014 because credit score information was collected starting then. This figure displays several features of note. First, the rejection rates, not surprisingly, vary greatly by respondents’ credit scores. The rejection rate for the least creditworthy group (those with a score of 680 or less) is nearly three times that of the middle-risk group. Second, the trends over time also vary across the groups. While rejection rates have remained steady at around 8 percent for the most creditworthy group, they have increased somewhat for the other groups; for example, the rejection rate for the least creditworthy group rose from 51 percent in February 2014 to 55 percent in October.

To highlight the richness of the SCE Credit Access Survey’s data, we next turn to a specific credit product: auto loans.

Auto Loans—Experiences and Expectations

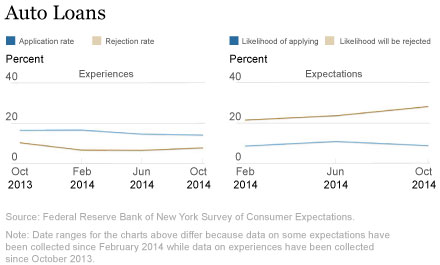

The left panel in the figure below shows trends in experiences with auto loans. The application rate (that is, the rate of having applied for an auto loan over the past twelve months) has stayed in a narrow range—between 14 and 17 percent—since the start of the series. The rejection rate has also oscillated within a small band, between 6 and 10 percent. Turning to expectations, reported on the right side of the panel, we see that the mean perceived likelihood of applying for an auto loan over the next twelve months has remained stable at 8 to 10 percent. On the other hand, the mean perceived likelihood of the auto loan application being rejected, conditional on applying over the next twelve months, has steadily increased from 21 percent in the February 2014 survey to 28 percent in the recent October survey. Moreover, expected rejection rates are higher when compared to current actual rejection rates. This doesn’t necessarily imply that respondents have biased expectations. One possible explanation is that expectations are elicited from all respondents who report some positive probability of applying for an auto loan, while we observe actual outcomes for only those who did, in fact, apply for an auto loan. This pattern would be observed if those who chose to apply for auto loans were those who were more optimistic or confident about getting approved.

Conclusion

These credit access series will be updated every four months. We hope that these data will help readers and policymakers better understand the state and evolution of credit access for different segments of U.S. society, and that they will inform appropriate policy prescriptions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Basit Zafar is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics