A successful hybrid is an offspring of two species that, in a new environment, is better suited for survival than its own parents. Evolution in the financial “ecosystem” seems to have driven the emergence of hybrid intermediaries.

In several previous posts, I commented on the evolution of banks in particular and financial intermediation as a whole (see the first, fourth and seventh posts in our July 2012 series on bank evolution). In those posts, I argued that you can’t really understand the evolution of the banking firm without paying close attention to the concurrent evolution in the technology of financial intermediation. In other words, we can’t say much about the importance of banks as intermediaries, or about the rising role of shadow banking, without careful consideration of how intermediaries today match the supply of funds and the demand for funds.

It’s probably accurate to say that you no longer need a bank to complete the process of financial intermediation, or at least not a bank as we traditionally define it—that is, an entity focused on deposit-taking and loan-making operations (in other words, a commercial bank). Instead, given the growth of asset securitization and other market innovations, intermediation now takes place through the combined input of a quite diverse group of firms, each contributing some specialized service along much more complex credit intermediation chains (see Pozsar, Adrian, Ashcraft, and Boesky, 2010).

Does this mean that banks are dead and shadow banks are flourishing? Not necessarily. Banks have adapted to the changing technology of intermediation: if a diverse set of nonbank firms becomes increasingly relevant to the process of intermediation, then a bank can expand its organizational boundaries by incorporating these different entities under common control. This scenario suggests a driver for the evolution of banks into increasingly complex financial conglomerates comprising a wide variety of nonbank entities. In fact, that is precisely the type of evolution in bank holding companies (BHCs) that we have observed in the United States over the past thirty years or so.

This is not just academic digression. Adopting this organizational approach takes us to the heart of what an intermediary is today. In large part, it’s still the same set of actors as in the past (commercial banks), but they’re wearing different costumes (complex BHCs). In other words, much intermediation is still done by, say, Bank of America, Citibank, or JPMorgan Chase (JPMC), but it isn’t conducted only through their commercial bank subsidiaries; it’s also done through the combined efforts of myriad nonbank firms, including broker-dealers, underwriters, insurance firms, asset management companies, specialty lenders, and others. Financial intermediation goes on in the shadows but with some important qualifications on the specific shade of gray.

I call these conglomerates hybrid intermediaries. Why hybrid? Because if one looks in isolation at the separate entities controlled by the conglomerate, none of them has as its core business model intermediation per se. However, when you take a look at the organization as a whole, then you start to recognize the potential for broad provision of intermediation activity.

BHCs are certainly the best example of hybrid intermediaries. But then, what prevents nonbank financial firms from pursuing a similar organizational strategy? What prevents, say, an investment firm, an insurance company, or an asset manager from turning into a similar conglomerate? In fact, that has been happening. Below is a table from Cetorelli, McAndrews, and Traina (2014) showing the number of mergers and acquisitions that took place in the United States between 1990 and 2013 involving firms categorized as belonging to one of ten sectors: banks, asset managers, broker-dealers, financial technology companies, insurance brokers, insurance underwriters, investment companies, real estate companies, thrifts, and specialty lenders. (Click here for a larger version of this table.) The table shows significant within-sector consolidation—evidenced by the large numbers along the main diagonal of the matrix—but also significant dynamics “off diagonal,” reflecting nonbanks buying other types of nonbanks.

Does this mean, then, that all modern financial firms have turned into hybrid intermediaries? Maybe not, but I would posit that a firm couldn’t be a successful modern intermediary without having the organizational structure of a financial conglomerate (of course, a firm could still be a successful traditional intermediary, like the thousands of community banks and other niche lenders, but that’s a different story, and one that doesn’t contradict my argument). Is there any evidence of nonbank firms turning into hybrid intermediaries? This is a bit difficult to address, because it’s hard to get good, complete data on the full organizational structure of conglomerates, and also because almost by definition it may be hard to identify a nonbank firm as a hybrid intermediary (so we’re back in the shadow after all).

There is, however, an interesting case we can use: while it’s true that it is usually hard to look “under the hood” of conglomerate firms, U.S. BHCs are the exception because they’re required to report their full organizational structure and any changes to regulators. How is this helpful? After all, BHCs are already in the camp of hybrid intermediaries, and therefore are probably already displaying similar organizational structure. But we can exploit the fact that after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, a few large, nonbank financial firms converted to BHCs. Interestingly, these firms had no intention of changing their primary activity into core commercial banking. Their decision was driven instead by the exceptional circumstances following Lehman, manifested in both severe market funding distress and potential opportunities for business expansion. At the same time, these are all firms that had nevertheless developed significant roles as financial intermediaries (and were, in fact, experiencing financial distress as a result).

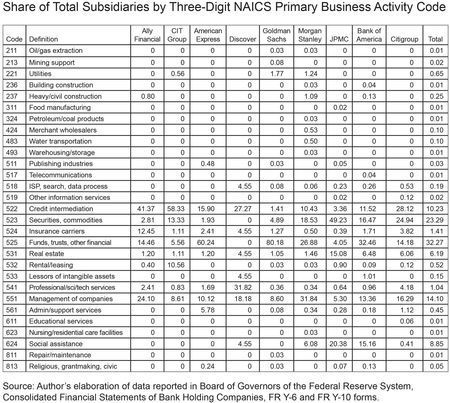

To study these entities, I collected BHC regulatory data on the full organizational trees of American Express, Discovery Financial, Ally Financial, and CIT Group (core business: specialty finance), as well as Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs (core business: investment banking). For comparison, I collected data for the three largest and most representative BHCs with true banking origins, JPMC, Bank of America, and Citigroup.

By looking at these firms, I can then draw a reasonably clean comparison across financial conglomerates with ex ante heterogeneous organizational histories and heterogeneous core business activit

ies, with some coming from the core banking side of the industry and some from other directions. Finding similarities in their organizational structure would be an indication of convergence toward the hybrid intermediary business model, and an indication that the path toward hybrid intermediation isn’t exclusive to firms with banking origins.

The table below summarizes the data on the organizational trees of these entities, reporting the share of total subsidiaries by their primary business activity, according to their three-digit NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) code classification. (Click here for a larger version of this table.) As the data indicate, the breadth of industries within the organizational footprint of these firms is quite large, ranging from oil and gas extraction plants (NAICS 211) all the way to religious, grantmaking, civic, professional and similar organizations (NAICS 813). Of course, each firm displays a certain degree of specificity in its organizational structure. However, the data also show a substantial degree of similarity across all firms, irrespective of their original business model. In particular, the bulk of the subsidiaries, across all firms, are credit intermediaries (NAICS 522); securities dealers, brokerages, investment banks, and other financial investment activities (NAICS 523); insurance carriers (NAICS 524); and investment funds (NAICS 525). Across all conglomerates, these subsidiaries accounted for more than 67 percent of the total. Adding to these numbers the share of subsidiaries that are just the controlling entities within the organizational tree (intermediate holding companies, NAICS 551), we account for more than 80 percent of subsidiaries across all firms. Put differently, and again acknowledging necessary idiosyncrasies among these firms, we wouldn’t have such an easy time recognizing which conglomerate was which just by looking at their organizational structure and the scope of subsidiaries that they own.

Financial intermediation has therefore evolved toward a technology where hybrid intermediaries thrive. Moreover, the evolution toward hybrid intermediation isn’t unique to banking firms, because similar conglomeration is evident in other areas of the financial industry. Besides helping to refine our understanding of what a modern bank really is, the concept of hybrid intermediaries helps in developing effective oversight and regulation of financial intermediaries. It suggests taking an approach focused on activities rather than on specific entities. And it perhaps suggests a redefinition of the scope of prudential regulation and, by extension, of the appropriate boundaries for access to official government backstops. But that’s a topic for another post.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Nicola Cetorelli is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics