Today, the New York Fed released the Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the fourth quarter of 2014. The report is based on data from the New York Fed’s Consumer Credit Panel, a nationally representative sample drawn from anonymized Equifax credit data. Overall, aggregate balances increased by $117 billion, or 1.0 percent, boosted by increases in all credit types except home equity lines of credit.

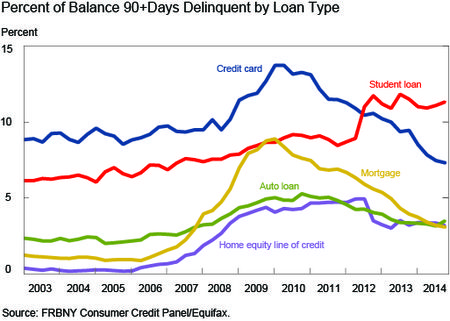

Delinquency rates improved overall, although the improvement was not across the board, as there were upticks in the delinquency rates for both student loans and auto loans. The chart below shows balance-weighted 90+ day delinquency rates by category of household debt.

The delinquency rates for mortgages, home equity lines of credit (HELOCs), auto loans, and credit cards peaked noticeably in the years following the recession, and have since fallen. In the case of mortgages, the 90+ day delinquency rate is now about 3.1 percent—still considerably higher than the roughly 1 to 1.5 percent rates we saw before the Great Recession. To some degree, this can be explained by the fact that the lengthy foreclosure process in many states is slow to clear out the stale stock of defaulted mortgages; however, a quick look at page 11 in our Quarterly Report reveals that the flow into serious delinquency also remains somewhat high by historical standards.

Credit card delinquencies have been steadily improving, and are now at some of the lowest levels we’ve seen since the start of our data in 1999.

Auto loan delinquencies have followed a similar trajectory, although we should note that in the most recent quarter, there is an uptick in the 90+ day delinquency rate. This uptick is even more pronounced in our measures of flows into delinquency, and we’ll continue monitoring this going forward.

The 90+ day delinquency rate for student loans, however, is different from the others—the rate has increased substantially since our student loan data began in 2003, and has now reached 11.3 percent. Student loans have the highest delinquency rate of any form of household credit, having surpassed credit cards in 2012. There are several reasons for this. Student debt is not dischargeable in bankruptcy like other types of debt; thus, delinquent or defaulted student loans can stagnate on borrowers’ credit reports, creating an ever-increasing pool of delinquent debt. Additionally, the measures of new delinquency in our Quarterly Report do reflect high inflows into delinquency.

Yet even these rather grim statistics don’t tell the whole story. This week, in a series of three blog posts, we will use our dataset to further investigate student loan balances and delinquencies. In the first post, we will update some descriptive statistics on student loan borrowers—we’ll look at who is borrowing, and how much they owe. In the second post, we’ll take a long look at how we calculate delinquency rates. We’ll use our data to approximate graduation cohorts, and use those cohorts to calculate default rates. In the third blog post, we’ll use the established cohorts to examine borrowers’ progress in paying down their balances. By the end of the week, readers will have a better understanding of student borrowing in the United States.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Meta Brown is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Meta Brown is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

These are all very good points – you’ll be interested in reading today’s Liberty Street Economics post, Looking at Student Loan Defaults through a Larger Window (http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2015/02/looking_at_student_loan_defaults_through_a_larger_window.html). We work through some different ways to look at student loan delinquencies and defaults and address many of your points. Indeed, the measure of 90+ delinquent that we discuss here includes any debt which the consumer is still required to pay back that is 90 or more days past due, and charge-off periods vary by loan types. However, from the borrower’s perspective, these debts still require repayment, so even if the lender charges them off, the fact that they are still on the credit report indicates that they remain a burden on the household balance sheet.

But what does 90+ days delinquent encompass? Consumer debts on credit cards, car loans, mortgages, private signature loans, and, even private student loans, are charged off at around 150 days delinquent. Federally guaranteed and direct student loans are never charged off, so, despite some fairly-significant post-default collections, these loans keep accumulating over time, as long as new loans are being issued, and thus their 90+ means 91 days to 25 years or more past-due. Default occurs after 270 with the federal loans. If the goal is to compare across different types of credit products, wouldn’t the correct delinq measure be 31-150 days delinq (counting nothing that is beyond 150)? Then a good post-default/post-foreclosure recovery measure would be to look at those in default (not delinquent). In both cases, you would also need to adjust for the credit risk: federal student loans don’t have underwriting, so, particularly after 2007, the credit scores of their borrowers would be much lower than those of borrowers of mortgages, car loans, credit cards, and private student loans. Another option would be to find a private loan product where the credit scores are quite low; this again may be quite difficult if looking at post-2007 origination cohorts. Finally, you would probably need to adjust for the long period between origination and first bill/first payment due, a condition which does not generally exist in private consumer lending.