Leaders of both developing and advanced economies believe that encouraging the development of small businesses will lead to job creation and economic growth. As such, many governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGO) promote the use of business training programs to help grow small businesses. For example, an international business literacy program called Start and Improve Your Business has been introduced in more than one hundred countries and reached more than 4.5 million potential and existing entrepreneurs between 2003 and 2010 according to the International Labour Organization. Similar programs have been undertaken also in the United States. The Small Business Administration, among many other programs, supports a network of Small Business Development Centers that provide free and low-cost business consulting and training. In this post, we show that the expected benefits of these interventions may vary widely between developed and developing economies.

The best evidence to date on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship training in the United States is from a study by Robert Fairlie, Dean Karlan, and Jonathan Zinman (hereafter FKZ) recently published in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. The authors analyze a randomized trial of entrepreneurship training provided through the “Growing America Through Entrepreneurship” (GATE) program sponsored by the Small Business Administration and the Department of Labor. This entrepreneurship training appears to have limited and short-lasting effects. Those offered free training were more likely to write a business plan and start a business during the first six months after training than the control group that was not offered free training, but these differences subsided over a longer time period. There was also little effect on the sales or profitability of those that did start businesses.

The limited effects of the GATE program may reflect the availability of other sources of support for potential business owners in the United States rather than ineffective training. The largest gains from training may be in developing countries where the informal sector of self-employed workers is large and markets for business training are scarce. A 2013 World Development Report on jobs indicates that self-employed nonagricultural workers make up about 45 percent of the labor force in many lower income countries. However, a 2013 review of the literature by McKenzie and Woodruff shows considerable heterogeneity in the effectiveness of business training programs. One interpretation of this heterogeneity is that not all entrepreneurs have the ability to increase their profits, let alone grow their small businesses into engines of economy-wide growth. The natural implication is that subsidies and training should be targeting those with the highest potential for growth. We describe the results of exactly such an intervention in Mexico where the effects of training have significant effects. For additional details, see the recent working paper by Calderon, Cunha, and De Giorgi.

Sample

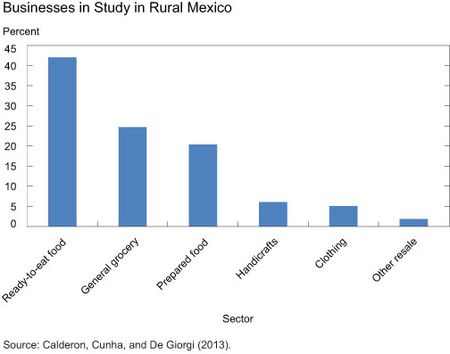

We provide here some evidence from an experiment that we recently ran in rural Mexico where the sample included a total of 875 female entrepreneurs in 17 villages. As shown in the chart below, the majority of firms (about 65 percent) are involved in the sale of food, either prepared (such as cheese or bread) or ready-to-eat (like tacos, hamburgers, or gorditas); general grocery and other resale comprise a little over 25 percent of the sample; handicrafts and clothing sum up to about 10 percent of the covered firms.

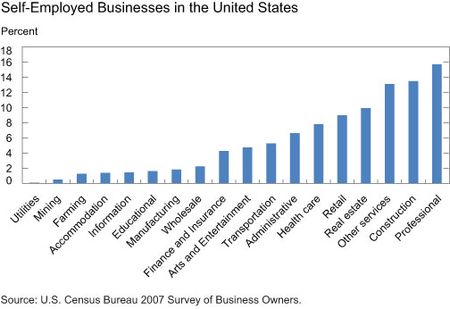

The businesses we worked with in Mexico are very small (on average they have about 1.5 employees including the owner) and have daily profits of around 140 pesos (approximately 11 U.S. dollars). These businesses differ substantially from those in the United States, even among only the self-employed. The chart below, computed from the U.S. Census Bureau 2007 Survey of Business Owners, shows that the self-employed in the United States are concentrated primarily in construction and professional services.

Intervention

We offered a business training program to a random set of entrepreneurs in our treatment villages while surveying the population of entrepreneurs both in treatment and control villages.

In 2009, we partnered with the NGO CREA to develop and implement a business literacy training program for small, female-headed firms in the retail or production sector in some of the villages near Zacatecas. The training program consisted of two four-hour classroom meetings per week and ran for six weeks—a total classroom time of forty-eight hours. The classes were designed to be small and inclusive, with two instructors and a class size of no more than twenty-five entrepreneurs.

The business literacy course covered six main topics, each taught in separate weekly modules. The topics varied from understanding costs (such as the difference between unit, marginal, fixed, and total costs) and how they should be measured, to price setting, product choice, and legal requirements. Given the participants’ low level of formal education, classes emphasized practical examples and encouraged students to relate the concepts to their own businesses.

Overall Effects

We find at follow-up interviews that those women who were offered the training have larger profits, revenues, and serve a larger number of clients. We also see, consistent with the intervention, an increase in the use of formal accounting techniques and an increase in the likelihood of formally registering with the government, which requires paying taxes but also allows firms to issue legal bills of sale. Furthermore, treated firms were able to reduce their costs and change the mix of products they sold; specifically, they increased the number of items sold, dropping higher cost goods and adding lower cost ones.

Are the better entrepreneurs getting better?

When we split the sample in above and below median profits before the intervention we see quite striking differences: by and large, the positive effects of the intervention consistently arise from those above the median of pretreatment profits, which we take as a proxy of entrepreneurial quality. This result differs from the GATE program in the United States studied by FKZ, which did not find significant differences in the effects of training across different subgroups, including using previous managerial experience as a proxy for entrepreneurial quality.

Timeframe of Influence

Are these short-run effects that will disappear over time? The simple answer is no; the effects last at least through the medium run. We collected two rounds of post-intervention data, one year and 2.5 years post-program implementation, and find that the effects of the treatment do not fade out into the medium run. These results differ substantially from the findings of FKZ for the United States.

Is it worth it?

These positive program impacts in rural Mexico, however, must be weighed against the costs of

running the business literacy classes in order to justify the intervention. In this example, a simple comparison of costs and benefits shows the program is indeed very cost-effective. What remains unclear is whether it is the individual upfront cost or the lack of information preventing individual entrepreneurs from seeking out advice. Regardless of the explanation, the study suggests there will be large gains to providing targeted business training in a developing economy that lacks other sources of business assistance.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Giacomo De Giorgi is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Benjamin Pugsley is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics