On the crisp morning of January 24, 1848, James Marshall, a carpenter in the employ of John Sutter, traveled up the American River to inspect a lumber mill that Sutter had ordered constructed close to timber sources. Marshall arrived to find that overnight rains had washed away some of the tailrace the crew had been digging. But as Marshall examined the channel, something shiny caught his eye, and as he bent over to retrieve the object, his heart began to pound. Gold! Marshall and Sutter tried to contain the secret, but rumors soon spread to Monterey, San Francisco, and beyond—and the rush was on. In this edition of Crisis Chronicles, we describe the excitement of the California Gold Rush and explain how it constituted an inflationary shock because the United States was tied to the gold standard at the time.

And the Rush Was On

As rumors of a gold discovery spread, an enterprising merchant named Samuel Brannan saw an even better opportunity than prospecting for gold and set up shop near Sutter’s Mill to supply what he anticipated would be a flood of miners needing picks, shovels, and pans. Carrying a small amount of gold in a glass vial, Brannan strode up and down Montgomery Street in San Francisco, then just a sleepy hamlet, extolling the great wealth that could be readily plucked from the foothills outside Sacramento. A kind of madness seized the 850 residents of the city, and as the San Francisco Chronicle noted on May 29, “the field is left half plowed, the house half built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes” (David Lavender, California: A Bicentennial History).

The 49ers

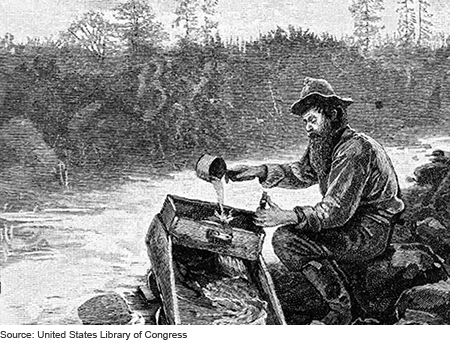

By May 1848, the stampede had begun. Miners from Mexico, Chile, and Peru, woodsmen from Oregon, prospectors from Australia, and merchants from the Hawaiian Islands all flooded into the Sierra foothills (Charles Ross Parke, Dreams to Dust). Monterey Mayor Walter Colton famously described the mania that gripped the region: “The blacksmith dropped his hammer, the carpenter his plane, the mason his trowel, the farmer his sickle, the baker his loaf, and the tapster his bottle. All were off for the mines.” At least half of the male population of Oregon poured south. By August 1848, an estimated four thousand prospectors poured into the California gold fields.

Even President James Polk felt the excitement. On December 5, 1848, he reported to Congress that if official reports had not confirmed the existence of vast quantities of gold in California, it would be difficult to believe the fantastic stories then in circulation. With the President’s seeming endorsement, gold fever gripped the nation, and a second, even larger wave of fortune seekers prepared for the journey west. Although prospectors continued to pour in from the Pacific Rim, including a wave of Chinese immigrants, this second wave from east of the Mississippi was made up of relatively well-educated and well-off young people, eager to seek their fortunes in the West. An estimated eighty thousand of them arrived in 1849 through a variety of routes—by boat around Cape Horn or to Panama, then across land, and back aboard another passing ship, or overland by a southern route through New Mexico and Arizona or across the Great Plains.

“Fabulously Rich Diggings”

It is largely from this articulate wave of immigrants—the self-described “49ers”—that we learn about the hardships of the journey and life in the mining camps. “Arrived at Bidwell’s Bar this evening. Here we found saint and sinner—especially the latter—rich and poor, educated and ignorant, well-disposed and vicious. In short, all sorts of people, and no law but that of the miner to govern them” (Parke, Dreams to Dust).

The first wave of fortune seekers—the 48ers—often had great success in extracting gold from what Lavender describes as “fabulously rich diggings.” But by the time the 49ers arrived, many of them not until late 1849, a number of the most profitable claims had been staked, and the “diggings” were more difficult and less fruitful. By the 1850s, fewer of the gold seekers prospered as they struggled to find a few ounces every day just to re-supply themselves with food and tools at exorbitant prices. In one of the most outrageous twists of fortune, laundry became so expensive that it was cheaper to ship dirty clothes to Hawaii for laundering. Not surprisingly, many of those who supplied the miners—like Sam Brannan, the Gold Rush’s first millionaire—did make a fortune.

Parke, like many of his fellow 49ers, became discouraged: “Yesterday we left the City of Sacramento and arrived here today (San Francisco) bound for home. This bay is full of craft of all kinds deserted by their crews almost as soon as they cast anchor. And here they lie rotting.” While Parke returned home, others elected to stay; by 1852, women were arriving and many immigrants were settling in.

More Monetary Shock Than Crisis

The gold rush constituted a positive monetary supply shock because the United States was on the gold standard at the time. The nation had switched from a bimetallic (gold and silver) standard to a de facto gold standard in 1834. Under the latter, the U.S. government stood ready to buy gold for $20.67 per ounce, a parity that prevailed until 1933. That commitment anchored prices, but the large gold discovery functioned like a monetary easing by a central bank, with more gold chasing the same amount of goods and services. The increase in spending ultimately led to higher prices because nothing real had changed except the availability of a shiny yellow metal.

In his excellent essay on gold standards, the economic historian Michael Bordo documents that the average annual U.S. inflation rate was many times lower under the gold standard (between 1880 and 1914) than in the subsequent 1946-2003 period. However, he shows that the gold standard led to more volatile short-term prices (including bouts of pernicious deflation) and more volatile real economic activity (because a gold standard limits the government’s discretion to offset aggregate demand shock). Bordo documents that short-run prices and real output were many times less volatile after the United States left the gold standard than before. Apart from their macroeconomic disadvantages, gold standards are also expensive; Milton Friedman estimated the cost of mining the gold to maintain a gold standard for the United States in 1960 at 2.5 percent of GDP ($442 billion in today’s terms).

Despite the demonstrable disadvantages of a gold standard, and notwithstanding that the U.S. inflation rate has remained at moderate levels for decades without one, some observers still call for the United States to return to a classical gold standard. Should we? Let us know what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s Cash Product Office.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

You write: “Apart from their macroeconomic disadvantages, gold standards are also expensive; Milton Friedman estimated the cost of mining the gold to maintain a gold standard for the United States in 1960 at 2.5 percent of GDP ($442 billion in today’s terms).” I think such estimates should be taken with a big grain of salt, not to say that they are completely meaningless. The question is not about absolute costs, but relative costs and more importantly, whether or not such costs can be known and quantified. Nations regularly went off the gold standard to fight wars. Is war then a cost of being on a paper-standard? These questions cannot be answered easily and they cannot be quantified in any serious or meaningful way. All we know is that some form of gold standard emerged naturally in the absence of legal tender laws or other forms of government intervention that outlaws the use of gold for monetary purposes. If a gold standard does emerge naturally, the cost question is irrelevant.

You write: “The increase in spending [due to the increase in gold supply] ultimately led to higher prices because nothing real had changed except the availability of a shiny yellow metal.” I think this is not borne out by the data. CPI rose less than 1% in the period 1845 to 1860. Price inflation accelerated meaningfully only when the US went off the gold standard in the 1860s to fight the Civil War. Your write: “However, he [Michael Bordo] shows that the gold standard led to more volatile short-term prices (including bouts of pernicious deflation) and more volatile real economic activity (because a gold standard limits the government’s discretion to offset aggregate demand shock).” I think you (or Bordo) are comparing apples with oranges. During the time of the gold standard in the 19th century, aggregate output depended much more on agriculture compared to the time without gold standards (i.e. post 1933). It is the natural fluctuations in harvests that contributed to rising and falling prices. Indeed, such price adjustments were the simple workings of supply and demand and there was nothing pernicious about them.

Thanks for adding that link. We had already seen Dr. Selgin’s response and found it informative, entertaining, and spirited—just the response we expected to get when we criticized gold standards. His lively response brings to mind a version of Twain’s quip “whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting over,” but here it’s “gold is for wearing and gold standards are for fighting over.” We made our views on a return to the gold standard pretty clear, so rather than challenge Dr. Selgin’s on his, it seems preferable to widen the discussion to include the views of the distinguished economists surveyed on the University of Chicago’s Economic Experts Panel: http://www.igmchicago.org/igm-economic-experts-panel/poll-results?SurveyID=SV_cw1nNUYOXSAKwrq. The resolution put to them was, “If the US replaced its discretionary monetary policy regime with a gold standard, defining a “dollar” as a specific number of ounces of gold, the price-stability and employment outcomes would be better for the average American.” The responses were overwhelmingly negative; not one of the roughly forty respondents agreed or even expressed uncertainty, while 40 percent disagreed, and 53 percent strongly disagreed. When the responses were weighted by the expert’s confidence in their answer, the responses were even more lopsided: 34 percent disagreed and 66 percent strongly disagreed. It’s a cliché to say economists always disagree, but here is an issue where they mostly agree.

Here is a rather critical response to your article by George Selgin, which you may find interesting: http://www.alt-m.org/2015/08/12/rush-to-judge-gold/

Thank you so much for responding so well to my questions.

Thanks for the questions, Bob. We certainly did pique your curiosity! Miners could use their gold to buy goods and services directly from merchants who would be willing to accept gold because they knew it was ultimately worth $20.67 per ounce. For example, miners could buy a drink with a “pinch” of gold dust. Alternatively, miners could deposit their gold in a bank in San Francisco (or elsewhere) in exchange for a deposit or currency (gold coins or bills issued by the bank). Some of this discovered gold made its way back to the Philadelphia mint where it was struck into coins. The whole gold-to-money conversion process got much cheaper, safer, and faster all around in 1854 when the U.S. mint opened a branch in San Francisco that began “converting miners’ gold into coins” (http://www.usmint.gov/about_the_mint/mint_facilities/?action=SF_facilities). There were also a number of private mints operating in San Francisco during the gold rush (the U.S. Constitution barred states from issuing currency, but not individuals). One private mint, Moffat and Co., closed in 1853 and sold its equipment to the San Francisco mint. The answer to your next major question is unavoidably wonky. In order to keep prices stable (the main rationale of the gold standard), the money supply (and hence gold stock) would need to grow at the same rate as real spending in the economy, assuming (not necessarily realistically) that the money stock turns over a constant number of times each period (constant velocity). This follows from the famous Quantity Theory of Money: MV=PQ, where M = money stock, V = velocity, P = price level, and Q= real spending per period. It follows (approximately) that ΔM = ΔP + ΔQ, where Δ denotes the change each period and ΔV = 0, that is, constant velocity. Thus, if real spending increases 2.5 % each year (ΔQ =2.5), then ΔM must equal 2.5 % if prices are to remain stable (ΔP=0). If money grows faster than the spending, prices rise; if money grows slower than the real spending, prices fall. Deflation (falling prices) was a chronic problem with the gold standard whenever real spending grew faster than the gold/money supply. Deflation can be pernicious because (if unexpected) it increases the real burden debt (debt deflation), which can lead to default. It can increase real wages; that sounds good, but it can increase unemployment. If you haven’t already you should read this account of the Wizard of Oz as a monetary allegory. It’s fascinating, instructive, and makes excellent parlor chatter: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937766?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Finally, here are some figures on gold extraction during the California gold rush: o In 1848, about 6000 miners obtained $10 million worth of gold. o In 1849, about 40,000 miners obtained between $20 million and $30 million worth of gold. o In 1852—the peak year of gold mining—about 100,000 miners obtained close to $80 million worth of gold. http://users.humboldt.edu/ogayle/hist383/GoldRush.html. The Australian gold rush that commenced in 1851 also added a lot of Au to the world supply. See http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/austn-gold-rush.

Thanks for the article, it raised my curiosity. Can you explain the process by which the addition of newly mined gold leads to an increase in the money supply? Are people using raw gold, weighed on a scale, to purchase goods and services? Did the treasury purchase this new gold to maintain the value of the dollar? What was the rate of increase in gold reserves required to accommodate credit expansion at the time? How much gold was actually extracted from Northern California in 1848-1850? When adding the costs of failed ventures, was the expense greater than the value of gold extracted? I especially enjoyed the part about how the discovery of gold immediately caused people to put down what they were doing and start producing mining equipment.