In September 2008, the U.S. government engineered a dramatic rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, placing the two firms into conservatorship and committing billions of taxpayer dollars to stabilize their financial position. While these actions were characterized at the time as a temporary “time out,” seven years later the firms remain in conservatorship and their ultimate fate is uncertain. In this post, we evaluate the success of the 2008 rescue on several key dimensions, drawing from our recent research article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

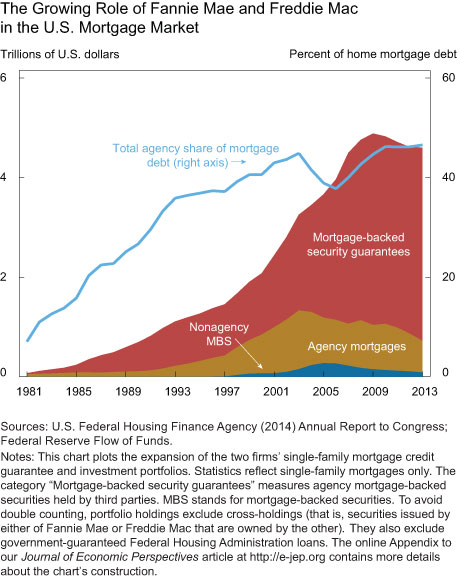

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that play a central role in the U.S. housing finance system, financing about half of the $10 trillion residential mortgage market. Both firms are publicly held and were created by acts of Congress to enhance the liquidity and stability of the secondary mortgage market and thereby promote access to mortgage credit, particularly among low- and moderate-income households and neighborhoods. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac engage in two principal activities: (1) creating “agency” mortgage-backed securities by insuring mortgage pools against credit losses; and (2) investing directly in mortgage assets. The two GSEs’ federal charters provide important competitive advantages that long implied U.S. taxpayer support of their obligations. As profit-maximizing firms, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac leveraged these advantages over time to become very large, very profitable, and very politically powerful. The chart below illustrates the GSEs’ rapid growth in terms of overall business size and share relative to the residential mortgage market.

In 2008, as the U.S. housing crisis intensified, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac became financially distressed. Their high leverage and concentrated exposure to the mortgage market turned out to be a recipe for disaster in the face of a large nationwide fall in home prices and the associated surge in mortgage defaults. As the GSEs’ stock prices plummeted and they began having trouble rolling over their debt, their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), placed the two firms into conservatorship, taking control on September 6, 2008, in an effort to conserve their value and allow them to continue operating as going concerns. Concurrently, the U.S. Treasury entered into senior preferred stock purchase agreements with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; under these agreements U.S. taxpayers ultimately injected $187.5 billion into the two firms.

Was a short-term public intervention necessary? Our paper argues “yes,” because of the central role of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the U.S. mortgage market, and the GSEs’ interconnections with the rest of the global financial system. We highlight three key points. First, stabilizing the GSEs allowed them to continue financing mortgages—both for home purchases and refinances. This was particularly important at the time because of the tight supply of other forms of mortgage finance, including a market freeze in the nonagency securitization market. Second, the government rescue supported overall financial stability. GSE debt and mortgage-backed securities were widely held by leveraged financial institutions and commonly used as collateral in short-term funding markets. Allowing credit losses on these securities would have exacerbated the weak capital and liquidity position of many already stressed financial institutions and raised the possibility of forced asset sales and runs. Third, foreign central banks and governments also held significant quantities of GSE obligations; a default by either or both firms could have had international political ramifications, and potentially undermined the perceived creditworthiness of the U.S. government itself.

Turning to the form of the rescue, our view is that an optimal intervention into Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would have involved the following elements:

- The firms would be able to continue their core securitization function as going concerns, supporting the supply of mortgage credit.

- The firms would continue to honor their debt and mortgage-backed securities obligations.

- The value of the common and preferred equity in the two firms would be extinguished, reflecting their insolvent financial position.

- The two firms would be managed in a manner consistent with broader macroeconomic objectives, rather than for just maximizing the private value of their assets.

- The structure of the rescue would prompt long-term reform within a reasonable period of time.

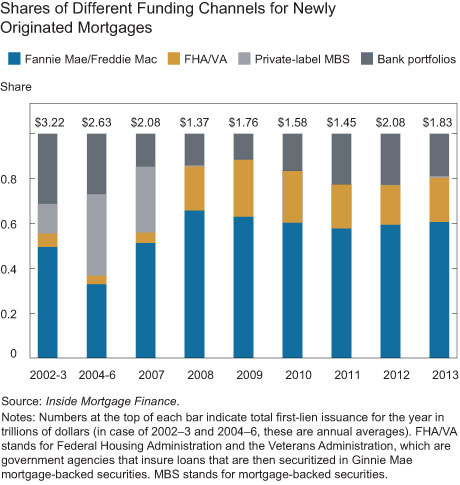

Evaluating the rescue against these goals, we believe that the conservatorships largely accomplished the first three objectives. The financial lifeline provided by the U.S. Treasury enabled Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to support mortgage supply through the crisis and its aftermath and to take up the slack left by the breakdown in nonagency securitization (see chart below), thereby supporting the fragile housing market. Holders of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities did not suffer credit losses, insulating the broader financial system from contagion effects. And both common and preferred equity holders were effectively wiped out, consistent with market discipline.

The conservatorships were arguably less successful on the fourth objective of aligning the activities of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with broader macroeconomic objectives during the Great Recession. By law, the conservatorships are intended to put the GSEs in a “sound and solvent condition” and to “preserve and conserve” their “assets and property.” But this focus conflicted at times with other public policy objectives. One example is the GSEs’ aggressive enforcement of “representations and warranties” whereby the firms “put back” a large number defaulted mortgages to originators. While these putbacks were typically legally justified, a consequence was an unhelpful tightening of underwriting standards and higher costs of mortgage lending after the financial crisis.

The conservatorships have also strikingly failed in relation to our fifth and final objective of producing long-term mortgage finance reform. As Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson wrote, “We described conservatorship as essentially a ‘time out,’ or a temporary holding period, while the government decided how to restructure the [government-sponsored enterprises].” However, starting the conservatorships turned out to be easier than ending them, and the “time out” has now stretched beyond its seventh year with no clear path to reform.

What’s next? Although there appears to be broad consensus that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac should be replaced by a private system, perhaps augmented by public reinsurance against extreme tail outcomes, substantial disagreement remains about how to implement such a system, and at present no end to the conservatorships is in sight. The many legislative proposals to date all reflect the crosscurrents of trying to protect the taxpayer, preserve support for the thirty-year fixed-rate mortgage, and keep homeownership affordable to a wide spectrum of borrowers. While the lack of action to date is not cause for optimism, the current situation provides a unique opportunity to put the U.S. mortgage finance system on a more stable footing, an opportunity that we hope is not wasted.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

W. Scott Frame is a financial economist and senior policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Andreas Fuster is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joseph Tracy is an executive vice president and senior advisor to the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

James Vickery is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Wipe out shareholders is a goal during a recession? And, what happens to share holders when you company is profitable? Why did the insolvent banks not have their share holders wiped out?

You guys need to research on net profit sweep. Let us know what you find out.

Without fnma and Fmcc with 30 year dream is killed. The government needs to stop stealing private property from investors. #fanniegate

It is time to let Fannie and Freddie rebuild capital and release them from cship in to remove taxpayer risk. US TSY perpetual profit sweep erodes private capital faith that they can invest alongside US TSY and not be subject to closed-door arbitrary policy making that ultimately hurts private capital. Without Fannie and Freddie, the systemically dangerous TBTF Banks (who’ve grown larger in this recession) would become originators and securitizers. If that is allowed to happen, the next round of bank bailouts will be much larger and financial damage would be generational. Time to let Fannie and Freddie get back to doing what they have done well for nearly 80 years.

Need more focus on Fannie/Freddie’s decision to take on poor quality debt