The Federal Reserve has kept interest rates at historic lows for the last six years, but eventually rates will return to their long-term averages. That means both policymakers and the public will once again be asking one of the classic questions in monetary economics: What are the impacts of rising interest rates on the real economy? Our recent New York Fed staff report “Interest Rates and the Market for New Light Vehicles,” considers this question for the U.S. market for new cars and light trucks. We find strong evidence that rising rates will dampen activity: Our model predicts that in the short-run a 100-basis-point increase in interest rates will cause light vehicle production to fall at an annual rate of 12 percent and sales to fall at an annual rate of 3.25 percent.

Background

Economic theory predicts that the durable goods market is a key channel through which monetary policy affects the real economy. Interest rate changes affect this market through two channels.

- Household expenditure channel

Higher interest rates raise the cost of borrowing for households, inducing a decline in demand for automobiles (see this Liberty Street Economics blog post for more about households’ financing of automobiles). Hence, sales and real prices should fall. Automakers will react to the decline in demand by curtailing production and their inventories may rise or fall, depending on the size of the sales decline relative to the decline in production.

- Firm inventory channel

Higher interest rates raise the cost of holding inventories for automakers, inducing them to economize on inventories by reducing production and by cutting real prices to raise sales. The overall impact on sales, however, isn’t clear cut. The reason is that reducing inventories dampens sales, whereas cutting prices increases sales.

The overall effect of increasing interest rates for both households and automakers, then, is ambiguous for sales and inventories. Indeed, this reasoning may explain why previous research has found little effect of real interest rates on sales and inventories in durable goods markets.

Our Approach

To capture the various ways interest rates affect the sales, real prices, production, and inventories of automobiles, we construct a dynamic market model that embeds the two channels described above. An innovation of our approach is that households and automakers face separate interest rates. This is both consistent with what we observe in practice and also enables us to disentangle the effects of the household expenditure and the firm inventory channels.

We estimate our model using high-quality data on automobiles from 1972 to 2011 and demonstrate that the model fits the data well. We then use the model to predict what happens to sales, real prices, and production when interest rates rise.

The Results

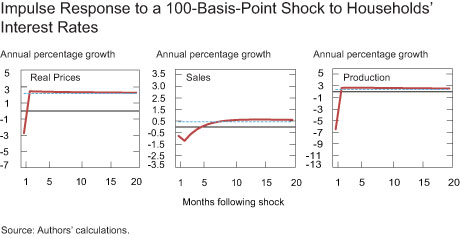

We begin by simulating a scenario in which the households’ interest rate rises 100 basis points unexpectedly, then slowly reverts back to its long-term equilibrium value. The model simulation enables us to track how the growth rates of sales, real prices, and production deviate from their long-term equilibrium values.

This exercise highlights the impact of rate changes through the household expenditure channel. The set of graphs below illustrates the model’s predictions: The dotted lines are the steady-state values of the variables, and the solid lines are the deviations from that value, given a 100-basis-point shock. The model predicts that the annual growth rate of sales immediately falls to -0.5 percent and slowly moves back to its steady-state value over eight months. In reaction to the rise in households’ interest rates, automakers anticipate the fall in demand and dramatically cut prices and production in the short run.

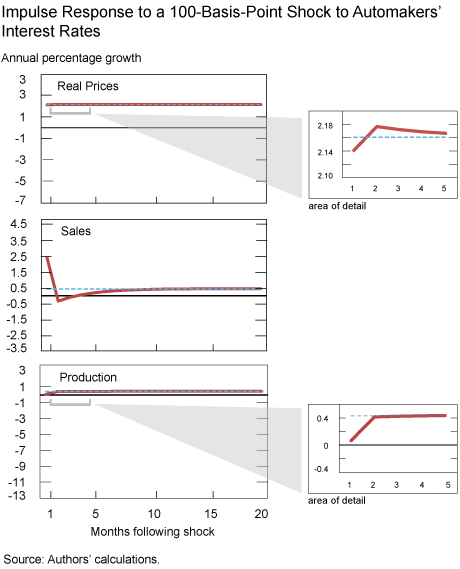

We then repeat this exercise, but this time consider an unexpected 100-basis-point increase to automakers’ interest rates to highlight the impact of rate changes through the firm inventory channel. The graphs below illustrate the model’s predictions; we have kept the scales fixed from the previous set of graphs, so as to provide for easier comparison. In response to the higher rates, which increase the costs of holding inventories, automakers look to shed their inventories. They accomplish this with both a small price decrease, which leads to a short burst of sales, and a small decrease in production (see the pull-out in the production growth graph).

The price impact is small, but its effect on sales is boosted by the dynamic nature of a household’s problem. Households recognize that automakers are decreasing real-price growth in the first month following the interest rate shock and then increasing prices in the second month (see the pull-out in the real-prices growth graph), leading households to shift their new auto purchases from future periods to the current period. Indeed, sales growth falls sharply in the second month.

Looking across the two sets of impulse-response graphs, we see that the 100-basis-point increase in households’ interest rates has a much bigger impact on real-price and output growth than the similarly sized shock to automakers’ interest rates.

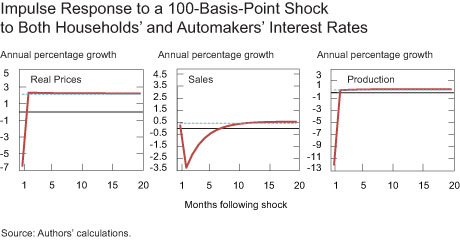

As a final exercise, we then increase both households’ and automakers’ interest rates by 100 basis points—the scenario that would occur under monetary policy tightening. The responses of households and automakers to common interest rate increases reinforce one another along some dimensions, while offsetting each other along others. As illustrated in the set of graphs below, this shock leads to large temporary declines in the growth rates of real prices and output.

Production falls by an annualized rate of 12 percent in the month immediately following the shock, which translates into a decline of 170,000 automobiles. The offsetting effects of the household expenditure and firm inventory channels mean that sales growth is initially close to its steady-state value, before falling at an annualized rate of 3.25 percent in the second month after the shock to interest rates and then slowly recovering back to the steady-state value.

Overall, we find evidence that interest rate changes have marked effects on sales and production in the automobile market, through both the household expenditure and firm inventory channels. Further, a 100-basis-point increase in households’ interest rates has a much bigger impact on real-price and production growth than the similarly sized shock to automakers’ interest rates.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Adam Copeland is a research officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

George Hall is the Fred C. Hecht Professor in Economics and Chair of the Department of Economics at Brandeis University.

Louis J.Maccini is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Economics at Johns Hopkins University.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comments and suggestions. Regarding the graphs, the growth rates of sales, production, and real prices return to their steady-state values in the long-run. For ease of viewing we cut off the charts at 20 months, before these variables had a chance to return to their steady state.

As a non-economist, it is unfortunate that economists use the term “impulse response” when the more apt engineering term here would be “step response.” Even in finance, one has a step up in basis. If I read the graphs correctly, your long run steady state results, e.g., showing increased production, are counter-intuitive. Is this so? I assume this was motivated by an expected federal funds rate hike in December. Unless this also includes directly engineering a hike in other loan rates, I think an impulse response study to a federal funds rate hike on auto loan and mortgage rates would be useful.

Lower inventory leads to lower price for automobiles and that leads to lower inflation and so that would appear to be counter productive