The image of a newly minted college graduate working behind the counter of a hip coffee shop has become a hallmark of the plight of recent college graduates following the Great Recession. Recurring news stories about young college graduates stuck in low-skilled jobs make it easy to see why many college students may be worried about their futures. However, while there is some truth behind the popular image of the college-educated barista, this portrayal is really more myth than reality. Although many recent college graduates are “underemployed”—working in jobs that typically don’t require a degree—our research indicates that only a small fraction worked in a low-skilled service job in the years following the Great Recession. We find that underemployed recent college graduates held a wide range of jobs and, while most of these positions were clearly not equivalent to jobs that require a college education, some were actually fairly skilled and well paid. Further, our analysis suggests that many of those who started their careers in a low-skilled service job transitioned to a better job after gaining some experience in the labor market.

Are Most Underemployed College Graduates Working as Baristas?

To examine the types of jobs held by underemployed recent college graduates—those aged 22 to 27 with at least a bachelor’s degree—following the Great Recession, we use American Community Survey data from 2009 to 2013. We classify a job as a “college job” if at least 50 percent of the workers in that job indicated that at least a bachelor’s degree is necessary; otherwise we classify the job as a “non-college job.” Over this period, roughly 45 percent of recent college graduates worked in a non-college job.

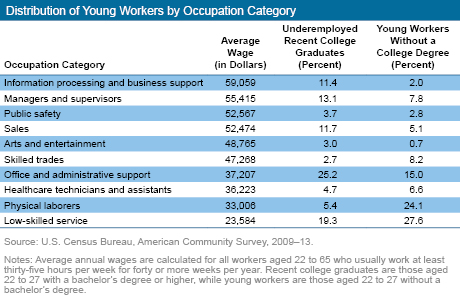

We grouped all of these non-college jobs into ten occupation categories, shown in the table below, ranked by the average annual wage paid to full-time workers. Within this set of jobs, the table also shows the share of underemployed recent college graduates compared to the percentage of young workers who did not have a college degree for each occupation category. The low-skilled service category—which includes waiters and waitresses, cashiers, bartenders, cooks, and, of course, baristas—stands out as the worst set of jobs, paying around minimum wage.

Contrary to popular belief, most underemployed recent college graduates were not working in low-skilled service jobs following the Great Recession. Indeed, nearly half were working in relatively high-paying jobs, with more than 10 percent working in the information processing and business support, managers and supervisors, and sales categories. At 25 percent, the largest share of underemployed recent college graduates worked in the office and administrative support category. While these jobs may not be as desirable as the typical college job, which pays around $78,500 annually, they are significantly better than low-skilled service jobs. That said, about one-fifth of underemployed recent college graduates—roughly 9 percent of all recent graduates—did work in a low-skilled service job.

Interestingly, underemployed college graduates were much more likely to be working in higher paying jobs than those without a college degree. This pattern is particularly evident in the highest-paying occupation categories that tend to emphasize cognitive skills and decision making—skills that are often learned in college—such as the information processing and business support, and managers and supervisors categories. Although about 40 percent of underemployed recent college graduates were employed in the four highest-paid categories of non-college occupations, only 18 percent of young workers without degrees held these types of jobs. By contrast, more than half of those without a college degree were working in the low-paying physical laborers and low-skilled service occupation groups, double the share for recent college graduates. Moreover, though not shown in the table, underemployed recent college graduates tend to earn more than similarly aged young workers without a college degree within each occupation category. So it appears that a college degree confers significant economic benefits on many graduates, even on those who find themselves underemployed at the start of their careers.

Transitioning to Better Jobs

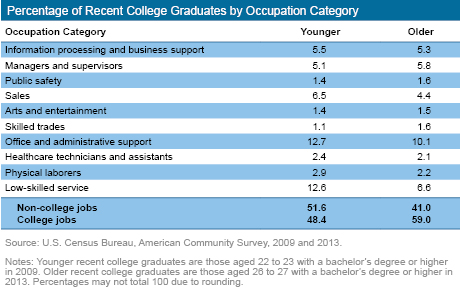

As we have shown previously, many underemployed college graduates find better jobs before too long. Underemployment typically falls as new graduates spend time in the labor market, a pattern that has held for decades. We illustrate this point further in the table below by examining the jobs held by those who graduated in the depths of the Great Recession. We compare the jobs held by younger graduates in 2009 (aged 22-23) to older graduates in 2013 (aged 26-27) to examine the labor market outcomes of those who graduated at around the same time. Overall, the share of graduates who worked in college jobs in their mid-twenties (59 percent) was larger than the share who worked in those jobs in their early twenties (48 percent).

In addition, the composition of jobs held by recent graduates changes within the underemployed occupation categories as workers age. The percentage who are employed in the low-skilled service category drops by half, suggesting that these jobs were temporary for a good number of young graduates. By age 26 or 27, only 6.6 percent were still working in these low-paying jobs. The other two groups with the most significant declines include office and administrative support, and sales. Though we cannot identify which jobs graduates tend to move into since our data are cross-sectional in nature—that is, workers may be shifting into other non-college jobs or into college jobs—these figures suggest that many underemployed graduates, particularly those who start in a low-skilled service job, are able to transition to better jobs as they gain more experience.

Demand for College Graduates Is Picking Up

In the weak labor market that followed the Great Recession, the prevalence of underemployment among recent college graduates reached highs not seen since the early 1990s. However, contrary to popular perception, our work reveals that most underemployed college graduates were not forced into low-skilled service jobs in the wake of the recession. In fact, many of the jobs these graduates held, while clearly not equivalent to jobs that require a college degree, appeared to be more oriented toward knowledge and skill when compared with the distribution of jobs held by similarly aged workers who lacked a college degree. Furthermore, underemployment appears to be temporary for many young graduates, part of an expected transition from school to the labor market. The good news is that while the demand for college-educated workers stagnated following the Great Recession, it has picked up in recent months—a trend that should provide more opportunities for college graduates to find good jobs going forward.

For additional information on this topic, explore our interactive web feature on The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Jaison R. Abel is a research officer in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Jaison R. Abel is a research officer in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics