In a recent post, we presented some preliminary evidence suggesting that corporate bond market liquidity is ample. That evidence relied on bid-ask spread and price impact measures. The findings generated significant discussion, with some market participants wondering about the magnitudes of our estimates, their robustness, and whether such measures adequately capture recent changes in liquidity. In this post, we revisit these measures to more thoroughly document how they have varied over time and the importance of particular estimation approaches, trade size, trade frequency, and the dichotomy between investment-grade and high-yield bonds.

Weighting Matters

As discussed in our earlier post, we don’t have access to quote data for corporate bonds, which trade over the counter. We therefore estimate “realized” bid-ask spreads by comparing—for a given bond—prices when a customer buys from a dealer (at the dealer’s offer price) to prices when a customer sells to a dealer (at the dealer’s bid price). We calculate the spread for a given bond and day using average (volume-weighted) buy and sell prices, and then average across bonds. Our calculations are based on Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

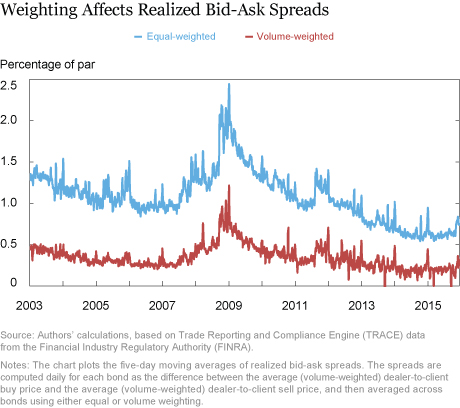

An important consideration in calculating the average daily spreads across bonds is how bonds with varying daily trading volumes are weighted. The blue line in the chart below plots the spread calculated on an equal-weighted basis, as we employed in our earlier post. The red line plots spreads weighted by daily volume across bonds. The two series are highly correlated, but the red line is appreciably lower, with average spreads in 2015 (through December 11) of 0.62 percent of par under the former method, but only 0.21 percent of par under the latter. Also, the volume-weighted spreads have declined less, if at all, relative to pre-crisis spreads.

Trade Size Matters

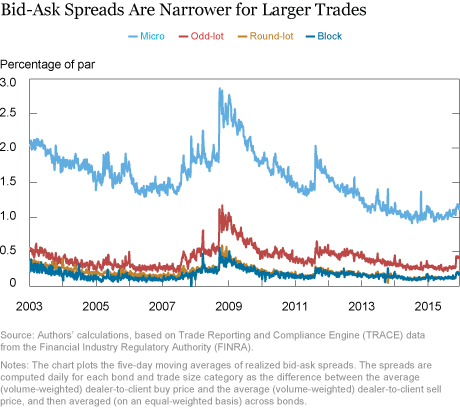

The fact that the weighted and unweighted approaches yield such different spread levels suggests that bid-ask spreads vary depending on daily trading volume. In fact, Edwards et al. and Bernhardt et al. have shown that transaction costs decline with trade size. They argue that in markets with a private negotiation phase, dealers offer better prices to large clients with repeat business potential. To account for that, we calculate spreads for four different trade size groupings (as is done in some academic papers): micro (under $100,000), odd-lot ($100,000 to $1 million), round-lot ($1 million to $5 million), and block (above $5 million).

Our findings (below) confirm that spreads are indeed narrower for larger transactions; average spreads in 2015 (through December 11) are 1.04 percent for micro trades, 0.28 percent for odd-lot trades, 0.13 percent for round-lot trades, and 0.13 percent for block trades. Despite those differences, the patterns of spreads over time are broadly similar. Moreover, once we disaggregate by trade size, we find that equal-weighted average spreads are very similar to volume-weighted average spreads.

Trading Frequency Doesn’t Matter

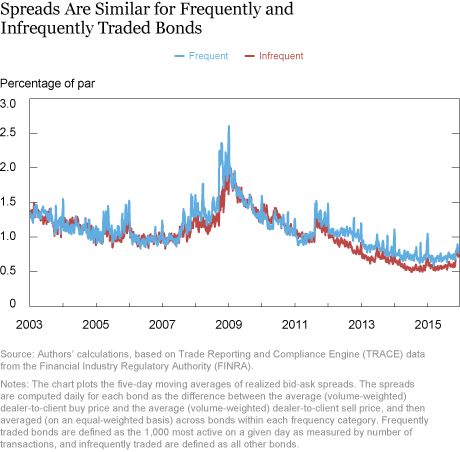

In contrast, bid-ask spreads are quite similar for frequently and infrequently traded bonds, as shown below (and consistent with the findings in this study, despite differences in methodology). Frequently traded bonds are defined as the 1,000 most active on a given day (by number of transactions), and infrequently traded are defined as all other bonds.

Investment-Grade versus High-Yield

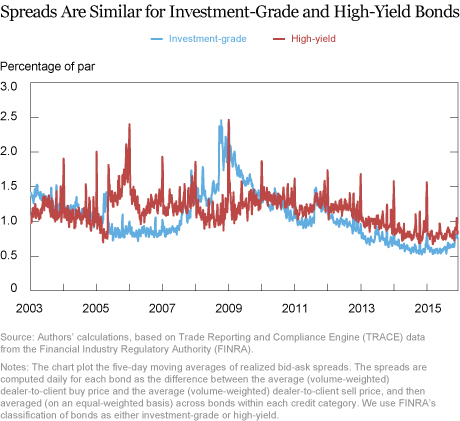

A natural question is whether safer (higher-rated) bonds are cheaper to trade than riskier (lower-rated) bonds. We investigate with a simple breakdown between investment-grade and high-yield bonds. In fact, average spreads are similar for the two groups (see below), whether calculated on an equal-weighted basis, as shown below, or a volume-weighted basis.

Price Impact and Aggregation Frequency

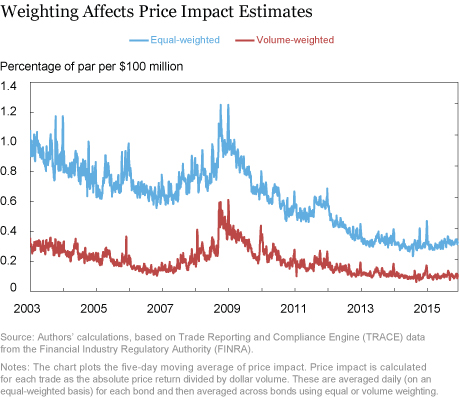

As in our earlier post, we estimate price impact as the absolute price change divided by trading volume (Amihud 2002). We do this on a trade-by-trade basis, then calculate the equal-weighted price impact for a given bond and day, and then lastly, calculate the average across bonds for a given day. As with the bid-ask spread calculations, weighting matters. The blue line below shows the final average price impact calculated on an equal-weighted basis and the red line on a volume-weighted basis. Perhaps not surprisingly, the volume-weighted estimate is appreciably lower, but both estimates follow similar paths over time.

We find that price impact across various bond categories follows patterns similar to bid-ask spreads. Price impact is thus very similar for bonds with frequent and infrequent trading, and the investment-grade and high-yield price impacts are also of similar magnitude. Perhaps one surprising result is that price impact per unit volume declines with trade size. This may be explained by our approach of calculating price changes using transaction prices, which effectively incorporate part of the bid-ask spread (which also declines with trade size).

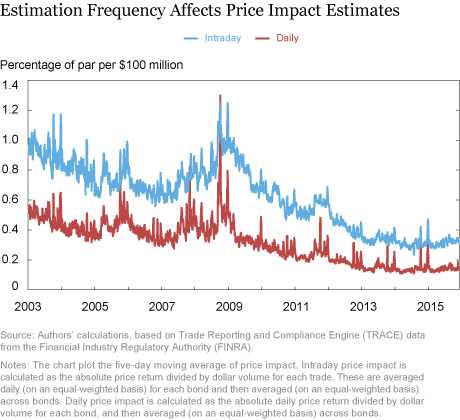

One way to reduce the spread’s effect on our price impact estimates is to calculate price impact over a longer interval that incorporates multiple transactions. We therefore repeat the price impact analysis described above except that we calculate the measure on a daily basis for each bond, instead of on a trade-by-trade basis. The daily price change is calculated from the first trade of the day and the daily volume excludes the first trade for consistency. As shown below, price impact is indeed much lower when calculated on a daily basis, which may reflect the fact that the measure incorporates less of the bid-ask spread and perhaps other factors that cause the long-run price impact to be lower than the short-run impact.

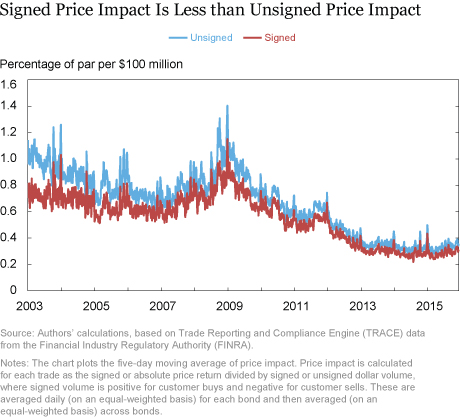

Signed versus Unsigned Price Impact Analysis

Lastly, we calculate price impact measures that account for the sign of both the trade and price change. Trades between dealers and customers are assumed to be initiated by customers, allowing us to sign dealer-customer trades (this analysis ignores interdealer trades). In addition to estimating price impact as absolute price change divided by trade size as before, we calculate signed price change divided by signed trade size, where signed trade size is positive for customer buys and negative for customer sells. For consistency, we estimate the unsigned price impact for the same sample of dealer-customer trades.

The results, shown below, suggest that knowing the signs of the trades does not matter much; signed and unsigned price impact estimates are reasonably similar, although the signed estimates are somewhat smaller and decline somewhat less over time.

In Sum

The results presented here reinforce our earlier message that corporate bond market liquidity appears ample based on the bid-ask spread and price impact measures. Nonetheless, some analysts argue that liquidity has in fact deteriorated, albeit in a way that is missed by the measures examined here. Indeed, an important caveat is that our measures cannot be estimated for bonds that trade rarely (for example, once a day). While this limitation is difficult to address, we will assess liquidity metrics across finer subgroups of bonds, in our next post.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is the associate director and a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael J. Fleming is a vice president in the group.

Erik Vogt is an economist in the group.

Zachary Wojtowicz is a senior research analyst in the group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics