Editors’ note: With this post, Liberty Street Economics launches an occasional series featuring interviews with our economists about their areas of expertise or recent research. In today’s post, Trevor Delaney, one of our publications editors, caught up with Jason Bram, a research officer in our Regional Analysis division to discuss how snowstorms do, or don’t, affect New York City’s economy. With a bit of snow expected here this weekend, the timing is auspicious.

Q: Tell us about the “weekend snowstorm” effect in New York City.

A: The short answer is that major New York snowstorms are remarkably likely to occur on weekends. If we focus on snowstorms that dumped more than fifteen inches in Central Park, there has been a total of sixteen major storms in the past seventy-five years, spanning anywhere from one to three days. Then if we narrow that group to storms that began on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday—and call those “weekend snowstorms”—one would expect about 43 percent (three of seven) of them to fall on a weekend. Yet it turns out that thirteen of the sixteen storms, or 81 percent, fell on a weekend.

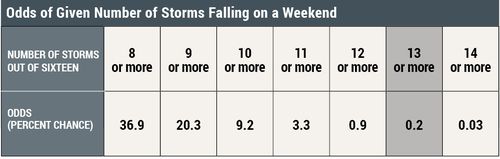

Q: Thirteen out of sixteen? What are the odds of that?

A: They’re remarkably low—a snowball’s chance in hell! Of sixteen storms, you’d expect about seven to start on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday—that’s because seven of sixteen works out to about the same proportion as three out of seven days of the week. The odds of thirteen or more falling on a weekend are 0.2 percent or 500 to 1.

Q: The last big blizzard in our region, in January, covered New York and several other East Coast cities with over two feet of snow. Does that much snow have any lasting economic impact?

A: Actually, there is no evidence (or theory) suggesting that major snowstorms affect the local economy for more than a couple days. Sure, the January storm disrupted travel for a day or so and cost the City and others quite a bit of money. Public transit shut down for about twenty-four hours, and nonessential driving was banned for almost as long. Most restaurants and shops, not to mention Broadway theatres, closed down for Saturday afternoon and evening and, of course, construction projects and other outdoor activities had to halt. Yet, by Monday morning—or even early Sunday afternoon—much was back up and running.

Long lines at the grocery stores before the storm illustrate that this kind of storm typically merely shifts the timing of economic activity by a few days. Still, one can certainly empathize with theatergoers who, after waiting months to see “Hamilton,” didn’t get to go. The bottom line is, when you look at monthly or even weekly economic indicators, you rarely see a blip, even after the most severe blizzards.

Even a much more destructive and damaging storm like superstorm Sandy, which devastated many individuals and businesses, is unlikely to have much of a long-term economic impact—say, of more than a few weeks—except on some very localized areas.

“The bottom line is, when you look at monthly or even weekly economic indicators, you rarely see a blip, even after the most severe blizzards. ”

—Jason

Bram

Q: The January blizzard was yet another weekend storm. Would a weekday storm have had a bigger impact?

A: Probably not. Even the rare midweek storms do not have much of an economic impact. But their immediate disruptive effects hit different kinds of businesses and would tend to be more widespread. For instance, schools, construction firms, offices, and manufacturers, as well as restaurants and bars that cater to the workweek crowd, would tend to be less disrupted by a weekend storm. Yet nightclubs, some restaurants, and many tourist attractions would generally be happier with a midweek storm, since that’s off-peak for them.

Q: How do economists evaluate the cost of a storm? Can it be measured with any precision?

A: Defining the cost of a storm is not as straightforward as it might seem. Cost to whom? Easiest to measure are direct costs, borne mostly by local governments for cleanup, dealing with accidents, overtime pay, salt, etc. But, of course, what’s a cost to the taxpayer may be an overtime bonus to a sanitation worker, or a big payday for a guy with a snowplow or an entrepreneurial kid with a shovel. At least some of this money will find its way back into the local economy.

Then there is the cost of forgone economic activity—lost production, which means lost pay for some hourly workers and lost revenue for some businesses. Of course, much of that is made up very soon after the storm, which is why you typically don’t even see a blip in monthly or even weekly economic indicators.

And finally, and probably hardest to measure, is what we call welfare or quality-of-life costs: extra time spent commuting, limited access to amenities, and disruptions to travel plans. But there are offsets here too, like the millions of kids who get to go sledding and enjoy other fun winter activities.

—Trevor Delaney

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Jason Bram is a research officer in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comment Mr. Ordway. That is exactly correct! Unless one can come up with some scientific explanation of why snowstorms might be more likely to hit NYC on a weekend (i.e. starting on a Friday, Saturday or Sunday), the probability of the next major snowstorm occurring in NYC on a weekend is indeed 43% (3 out of 7). It is a remarkable coincidence that so many storms have started on a weekend. This highlights the fact that, every once in a while, a highly improbable coincidence that may be interpreted as “clearly not random” is, in fact, just that: random.

To clarify, there is no causal relationship between major NYC snowstorms and the day of the week. The observation of 13 snowstorms in a set of 16 is just a coincidence. With more storms to observe the ratio would inevitably decline toward the 43% level implied by chance (given that the atmospheric physics involved do not have a relationship with our man-made seven day calendar). Said differently, the chance that the next major NYC snowstorm will start on a Friday, Saturday or Sunday is 43%, not 81%.