Correction: In the original version of this post, the chart “Average Daily Fedwire Payments Are Higher at Quarter-End” contained incorrect data. The chart has now been updated. We regret the error.

The federal funds market is an important source of short-term funding for U.S. banks. In this market, banks borrow reserves on an unsecured basis from other banks and from government-sponsored enterprises, typically overnight. Before the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve implemented monetary policy by targeting the overnight fed funds rate and then adjusting the supply of bank reserves every day to keep the rate close to the target. Before the crisis, reserves were generally in scarce supply, which periodically caused temporary spikes in the fed funds rate during times of high demand, typically at the end of each quarter. In this post, we show that the Fed actively responded to quarter-end volatility by injecting reserves into the banking system around these dates.

Quarter-End Volatility of the Fed Funds Rate before the Crisis

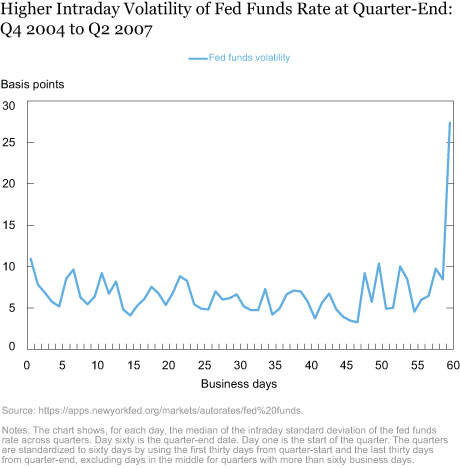

Large fluctuations in the fed funds rate around quarter-end were a feature in the fed funds market in the 1980s and 1990s and remain so today. In the three years before the financial crisis erupted in 2007, the average intraday standard deviation of rates on the last business day of the quarter (day sixty) was more than two and a half times the level observed on other days (see chart below). This heightened volatility hampered the Fed’s ability to keep the fed funds rate on target during quarter-ends.

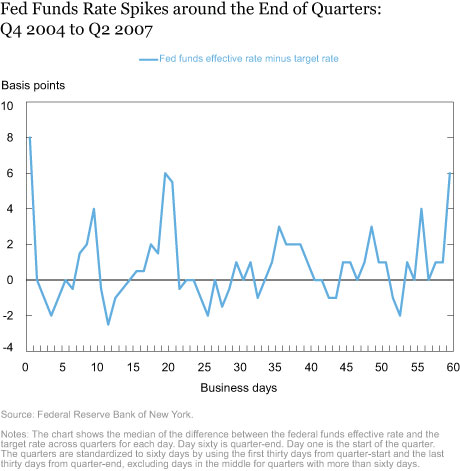

The heightened volatility typically caused the fed funds effective rate to deviate from target. This deviation increased by an average of 6 basis points on the last day of the quarter (day sixty) and by 8 basis points the following day (day one), as shown in the chart below. By contrast, on more “typical” days (excluding the quarter-end date plus the two days before and after it), the fed funds rate was within one basis point of the target, on average. The fed funds rate sometimes increased sharply at the end of months, which accounts for the spike on day twenty, but volatility on these days was not unusual (as shown in the previous chart).

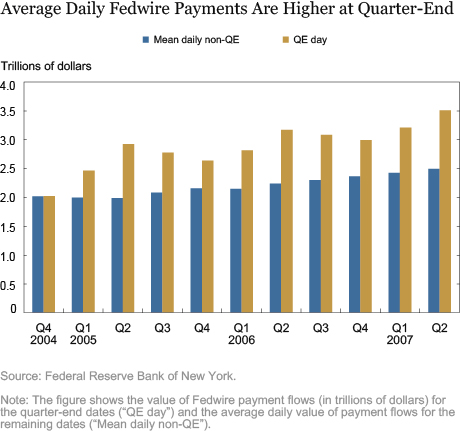

Banks may have needed additional funds to bolster their balance sheets on their quarter-end financial reports. Alternatively, the spike in the fed funds rate at quarter-end may have reflected increased bank demand for reserves to meet heightened transactional demand, because payment flows (including fed funds transactions) were consistently high on quarter-end days, as shown in the chart below.

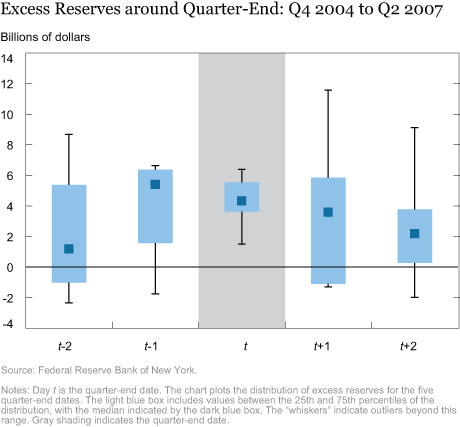

If banks had voluntarily held additional reserves at quarter-end to accommodate higher demand for funds, the fed funds rate may not have spiked to the same extent. But banks had no incentive to do so since, prior to 2008, reserves did not earn interest. Therefore, in order to stabilize fed funds rates around quarter-end dates, the Trading Desk (the Desk) at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York supplied extra reserves to meet the surge in demand. Moreover, the Desk planned to maintain relatively low levels of reserves on the other days in the same reserve maintenance period (in other words, the period over which banks’ required reserves are calculated). Otherwise, the supply of reserves would have exceeded demand over the non-quarter-end days of the maintenance period, pushing rates below the target once the quarter-end passed.

The box-whisker plot of the distribution of excess reserves in the chart below shows that the Desk maintained an average of more than $4 billion of excess reserves around quarter-end dates. In contrast, the Desk, on average, maintained less than $0.5 billion of excess reserves on non-quarter-end days of the maintenance period. The chart further indicates that the range of excess reserves was relatively narrow, between $3 billion and $6 billion on most quarter-end dates. This narrow range suggests that the Fed chose not to eliminate reserve demand shocks completely, a conclusion that was also reached by Bartolini, Bertola, and Prati.

Quarter-End Volatility of the Fed Funds Rate after the Crisis

The Fed’s response to the financial crisis of 2007-09 resulted in large amounts of excess reserves in the banking system. As a consequence, the Fed could no longer significantly influence the fed funds market on quarter-ends by modestly changing the level of reserves. Unlike in the pre-crisis period, the effective fed funds rate has tended to fall on recent quarter-end dates, as money market investors have faced reduced investment opportunities during the quarter-end and have shifted money into reverse repurchase agreements with the Fed instead. While some of the Fed’s tools and operating procedures have changed since the crisis, a quarter-end pattern remains evident in the Desk’s operations.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Alex Entz is on a fellowship at the City Colleges of Chicago.

John McGowan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Integrated Policy Analysis Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics