Since the financial crisis, bank regulatory and supervisory policies have changed dramatically both in the United States (Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act) and abroad (Third Basel Accord). While these shifts have occasioned much debate, the discussion surrounding supervision remains limited because most supervisory activity— both the amount of supervisory attention and the demands for corrective action by supervisors—is confidential.

Drawing on our recent staff report “Parsing the Content of Bank Supervision,” this post provides a peek behind the scenes of bank supervision, presenting a statistical linguistic analysis based on confidential communications from Fed supervisors to the banks they supervise. Our analysis tackles several fundamental questions: What are the precise supervisory issues being raised? What drives the issues supervisors bring up? How does bank supervision relate to the other two pillars of the Basel Accord: capital regulations and market discipline?

To answer these questions, we analyze the information in the demands for corrective action that supervisors place on banks. These demands, known as Matters Requiring Attention (MRAs) and Matters Requiring Immediate Attention (MRIAs), were standardized in 2008 in accordance with Supervision and Regulation letter (SR) 08-1. We use information on these issues during the years 2009-14, along with confidential supervisory ratings and bank characteristics from regulatory filings. Although the MRAs and MRIAs are largely qualitative, we categorize them quantitatively using a machine learning method known as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA).

Machine Learning and Supervisory Text

LDA is a computational linguistic method that defines a probabilistic model for generating topic labels for text. In particular, LDA assumes that the text of each document (here, an MRA or MRIA) is a distribution of single words or pairs of words. It then assumes that there are unobserved topics that can be assigned as labels to each document, and uses the word distributions in the text to estimate the labels. In our setting, we estimate weights for five different topics, and then use the most salient and important words for each category to label the topics.

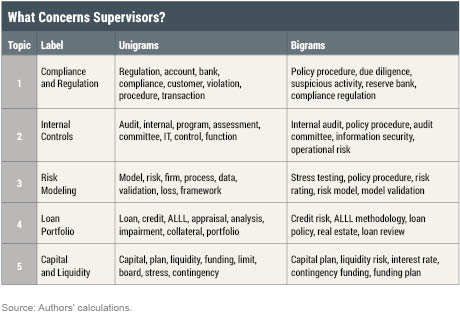

The taxonomy we estimate breaks supervisory issues into five broad topics. The table below shows the most salient words (“unigrams”) and pairs of words (“bigrams”) from the text of the MRAs and MRIAs, listed in order of frequency. However, the order of the topics themselves is arbitrary. We use these unigrams and bigrams to generate the labels in the second column. For example, for topic 1, we see that “compliance” and “regulation” are highly salient, while for topic 2, “audit” and other words related to internal controls are marked as salient. Correspondingly, we label these topics Compliance and Regulation and Internal Controls, respectively. We label topic 3 Risk Modeling, as it appears to reflect model risk concerns as well as stress. A notable feature of the Risk Modeling topic (and sign of the times since Dodd-Frank) is that its most frequent bigram is “stress testing.” Topic 4 concerns loan quality issues and is labeled Loan Portfolio; topic 5, relating to the capital and liquidity plans of banks and bank holding companies (BHCs), is labeled Capital and Liquidity.

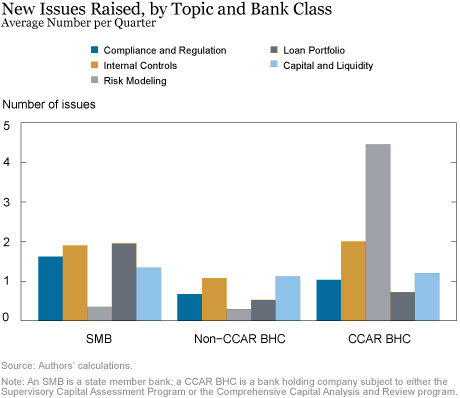

The incidence of these issues varies by type of institution. In the chart below, we plot the average number of new issues raised each quarter within each topic, across different classes of banks. Predictably, we see that Risk Modeling issues are the dominant issue for the CCAR BHCs—that is, any BHC subject to either the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP) or the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) program—and are negligible for non-CCAR BHCs and state member banks (SMBs).

Banks can have higher levels of supervisory issues for two reasons: concern and attention. If a bank is in distress, it may receive more MRAs as supervisors demand corrective actions. In fact, when we look at banks “of concern,” as indicated by a supervisory rating of 3 or higher (on a 1-5 scale, with 1 representing the best), we find that they have 0.35 more issues raised per quarter than a bank with a rating of 1 or 2, primarily related to the Loan Portfolio and Capital and Liquidity topics.

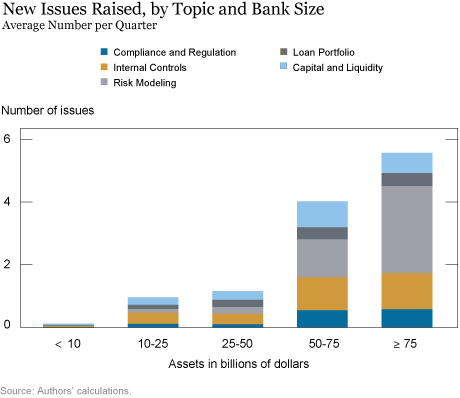

Banks may also receive more MRAs if they receive higher levels of attention, holding concerns equal. For BHCs not subject to CCAR, more issues are raised during and after their annual, full-scope supervisory exams. Moreover, CCAR BHCs have 5.6 more issues raised per quarter than non-CCAR BHCs, even after controlling for size, suggesting enhanced supervisory oversight. Almost half the increase is concentrated in Risk Modeling. To illustrate the increased supervisory oversight arising for the CCAR BHCs, we plot below—by topic and bank (asset) size—the number of issues raised. Along the x-axis, we bucket BHCs by asset ranges, and plot the average number of issues raised each quarter. Looking across the $50 billion threshold (roughly the threshold for CCAR status), we see a jump in the number of issues raised. Again, much of the increase arises from Risk Modeling issues.

LDA Meets Regression

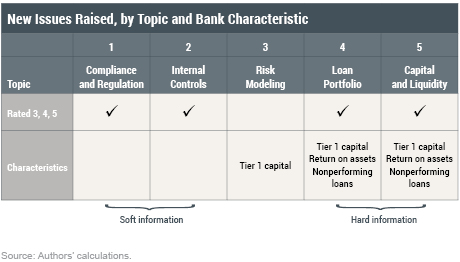

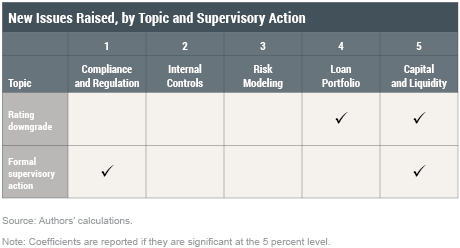

We next use regression analysis to look at the relationship between new issues raised by supervisors and bank characteristics. Specifically, we measure the correlation between the issues raised and a set of characteristics relating to bank health. The table below indicates which of those estimated correlations are statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level.

The bank holding companies and state member banks rated 3, 4, or 5 are more likely than better-rated counterparts to receive MRAs and MRIAs on every topic but Risk Modeling. In contrast, we see that the balance sheet indicators of bank health—nonperforming loans, return on assets (ROA), and tier 1 capital levels/ratios/adequacy—are strongly (and reassuringly) correlated with issues related to the Loan Portfolio and Capital and Liquidity topics. In contrast, the only major bank characteristic correlated with Risk Modeling is tier 1 capital.

Information: Soft and Hard

The pattern of findings above leads us to view Loan Portfolio and Capital and Liquidity issues as “hard” information issues pertaining to more objective, quantifiable, and transmittable data, while Compliance and Regulation, Internal Controls, and to some extent Risk Modeling are best seen as “soft” information issues that rely more on subjective judgment.

We also examined the relationship between the opening of MRAs and MRIAs and the implementation of other supervisory measures, such as rating downgrades or formal supervisory actions (more serious actions that are public). We find that hard information issues (Loan Portfolio and Capital and Liquidity) are associated with rating downgrades; Capital and Liquidity is also correlated with formal supervisory actions, as is the soft information topic Compliance and Regulation. Note that the middle columns of the table below reveal that increases in Risk Modeling issues are not associated with rating downgrades or increases in formal actions despite our findings that CCAR BHCs have a higher number of MRAs and MRIAs on those issues.

The third pillar of the Basel Accord, market discipline, works through investors rewarding banks that manage their risks prudently and penalizing those that do not. Of course, effective market discipline requires that market monitors pay attention and discern the relevant risks at opaque banks, where many concerns may be hidden behind the curtain.

To see if market monitors focused on the same topics as Fed supervisors, we examined the questions they raised during earnings calls for the largest BHCs, and we then assigned topics using the linguistic model we estimated for confidential supervisory issues. We found that monitors tended to raise questions that echoed the concerns of Fed supervisors, but only for topics related to hard information—Loan Portfolio and Capital and Liquidity. For issues related to soft information—Compliance and Regulation and Internal Controls—there was little correlation between Fed concerns and the questions raised by market analysts. In Risk Modeling, we found significant correlation between Fed concerns and analyst questions—an outcome that likely reflects the particularly public (relative to other supervisory issues) content of the stress test efforts.

In providing a look behind the curtain of bank supervision, we showed a complex environment with many types of supervisory concerns. By labeling the issues with a computational linguistic method and examining the correlation between supervisory concerns and bank balance sheets, we further categorized the issues raised by supervisors into hard and soft information categories. We also highlighted both the enforcement component of supervision—almost forty percent of supervisory actions were involved with Compliance and Regulation and Capital and Liquidity—as well as the complex interaction between market discipline and supervisory oversight.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Beverly Hirtle is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

David O. Lucca is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics