While bank regulation and supervision are the two main components of banking policy, the difference between them is often overlooked and the details of supervision can appear shrouded in secrecy. In this post, which is based on a recent staff report, we provide a framework for thinking about supervision and its relation to regulation. We then use data on supervisory efforts of Federal Reserve bank examiners to describe how supervisory efforts vary by bank size and risk, and to measure key trade-offs in allocating resources.

In principal, the objectives of banks and of society can differ for two fundamental reasons. First, banks have limited liability with deposit insurance and so they don’t fully account for the risks they impose on depositors and other creditors who fund them. Second, banks can impose costs—externalities—on the financial system and the economy when they fail. Because banks don’t take these external costs into account (by definition), they may take more risk than society would wish. Regulation and supervision are the tools that aim to align banks’ risk taking with the objectives of society as a whole, for the good of the financial system and economy.

The Difference between Regulation and Supervision

We distinguish regulation from supervision by the type of information the two use about a bank: “hard” or “soft.” In our model, we assume that regulators can only use hard information such as a bank’s business lines or the adequacy of its capital or liquidity. By contrast, supervisors can also use softer information, like the quality and centrality of a bank’s risk management, and whether it appears to be sidelined in important decisions.

Almost by definition, the reliance of supervision on soft information means that judgment must often inform supervisors’ decisions. We capture this element by allowing for false negatives and false positives in supervisors’ information, understanding that supervisors can observe a good signal although a bank is in trouble or a bad signal although a bank is fine.

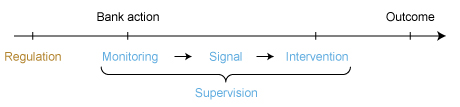

The diagram below shows the timeline in our framework. Once the hard regulations are set, the bank chooses a low-risk or high-risk action, for example, whether to engage in diligent risk management or not, and then later the risk is realized in an outcome, such as loan repayments or defaults. While the regulations are set at the beginning, supervisors are active throughout, first monitoring to produce information (a signal) about the bank’s action, then intervening based on the signal.

Supervisor’s monitoring has two benefits: it improves the reliability of the signal that supervisors act on and it curbs banks’ incentive to take excessive risk in the first place. The level of monitoring is chosen optimally taking both of those effects into account.

The benefit of intervention is that it can be chosen flexibly after the signal is observed. This flexibility is a big advantage of supervision compared with regulation, since it allows for an optimal response to the particular situation. However, commitment to more harsh intervention than is optimal ex post would have benefits on banks’ incentives ex ante.

One question is what we can infer from observing just the outcome, for example, when a bank fails? Did the bank take too much risk or was it just unlucky? Did the supervisors receive the wrong signal and fail to intervene? Our model suggests it’s nearly impossible to draw inference from an individual event just based on the bad outcome itself. Even in the best case, when a bank is prudent and supervisors take the right actions, extreme outcomes or “bad luck” can lead to default. The most troublesome scenario in our model, where the bank takes high risk that goes undetected by supervisors, is not necessarily more or less likely than the other possibilities.

Limits and Trade-offs in Supervision

Supervision is costly and, even if more is always better in our framework, supervisory resources are not unlimited. Supervisors face an economic trade-off and have to allocate their resources to where they are most valuable. How is this trade-off resolved in practice?

We study this question using data on hours worked by Federal Reserve supervisors and their ratings of bank holding companies, combined with balance sheet information from regulatory filings.

We first focus specifically on how supervisory attention (hours measured in log terms) relates to bank size (assets measured in log terms). We expect supervisory attention to increase with bank size, obviously, but are more interested how much hours increase with size. Comparing two banks, one twice the size of the other but otherwise similar, does the larger bank receive twice the attention, more than twice, or less than twice? Our regression estimates imply that if a bank is twice the size, on average and all else equal, it receives 62 percent more hours; so, supervisory attention increases less than proportionately with size.

While this may seem surprising, our model suggests two competing effects. On the one hand, a larger bank may warrant a disproportionately higher level of scrutiny because its failure would cause disproportionately more damage to the financial system and the economy. On the other hand, there may be economies of scale in supervision similar to the way a bank’s own headcount doesn’t necessarily double if it has twice the assets. Our 62 percent estimate is consistent with scale economies in supervision or a finding that larger banks actually do receive disproportionately more scrutiny but the effect is dominated by the scale economies.

We also look at the relation between supervisory attention and a bank’s riskiness as measured by its supervisory rating. Ratings are on a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is the safest and 3 or higher indicates moderate to significant concerns. To the extent that supervisors are assigned to reduce bank risk, as our model predicts, we expect to see a positive relationship between supervisory hours and ratings, that is, more supervisors working on banks with worse ratings. This result is exactly what we find in the data. For example, we estimate that a 3-rated bank receives 66 percent more hours than a safer 1-rated bank. To put this in perspective, supervisory attention increases about the same amount when a bank’s rating goes from 1 to 3 as when its assets double.

We also study how supervisory resources are reallocated across banks, first by comparing supervision before and after the 2008 financial crisis. We would expect more attention to large banks since the crisis, but how much more? And would we observe a decline in resources allocated to smaller banks?

Our analysis estimates that large banks (holding over $10 billion in assets) receive 65 percent more attention since 2008 while small banks receive 19 percent less. We also investigate how supervisory resources are reallocated within Federal Reserve districts when banks are in distress. In such situations, when distress demands supervisory resources, where is the concession? Our estimates show that resources are allocated away from small banks while the attention to large banks is unaffected.

Overall, the empirical results are consistent with the trade-offs derived in our model. As we see in the data, supervisory resources are allocated based both on the size and risk profile of an institution, but also on the overall resource constraints facing supervisors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

David O. Lucca is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

David O. Lucca is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Robert M. Townsend is a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics