Financial regulatory agencies issued guidance intended to curtail leveraged lending—loans to firms perceived to be risky—in March of 2013. In issuing the guidance, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation highlighted several facts that were reminiscent of the mortgage market in the years preceding the financial crisis: rapid growth in the volume of leveraged lending, increased participation by unregulated investors, and deteriorating underwriting standards. Our post shows that banks, in particular the largest institutions, cut leveraged lending while nonbanks increased such lending after the guidance. During the same period of time, nonbanks increased their borrowing from banks, possibly to finance their growing leveraged lending activity.

The Guidance

The interagency guidance was important not only because it laid out expectations of the supervisory agencies for the sound risk management of leveraged lending activities, but also because it targeted all supervised financial institutions actively involved in leveraged lending. The guidance outlined the agencies’ minimum expectations on a wide range of topics related to leveraged lending, including underwriting standards, valuation standards, pipeline management, the risk rating of leveraged loans, and problem credit management.

Subsequently, in November 2014 the agencies stated that the initial March 2013 guidance also applied to the leveraged lending of nonbank subsidiaries of bank holding companies, to new loans as well as loans acquired in the secondary market, and even to loans originated for distribution to other lenders. These additional, targeted stipulations potentially gave the guidance more teeth.

The agencies do not specifically define a leveraged loan in their guidance. Instead, they recognize that market participants use alternative definitions and allow participants to maintain their own definitions. Some market participants define leveraged loans off the borrower’s leverage; others use the loan (or borrower) rating; others rely on the stated purpose of the loan (for buyouts, acquisitions or capital distributions); and still others use the spread at origination (for example, loans with a spread of at least 150 basis points (bps) over LIBOR).

Did the Guidance Bind?

We assess the impact of guidance on leveraged lending activity by examining originations of syndicated term loans. We use a conservative criterion and classify a loan as leveraged if it has a spread over LIBOR of 250 bps or higher. We exclude credit lines because leveraged loans tend to be term loans. Our data are from Thomson Reuters Loan Pricing Corporation’s DealScan database.

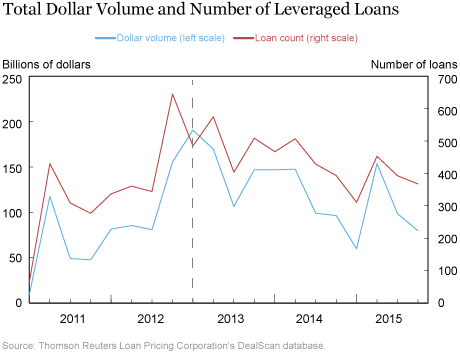

The chart below plots the dollar volume and number of leveraged loans originated (or refinanced) by banks and nonbanks (such as private equity firms) each quarter since the beginning of 2011. Consistent with the concerns of supervisory agencies, leveraged lending did indeed grow rapidly in 2011 and 2012. Activity peaked around the first quarter of 2013 and has declined since then, suggesting that the lending guidance may have slowed originations.

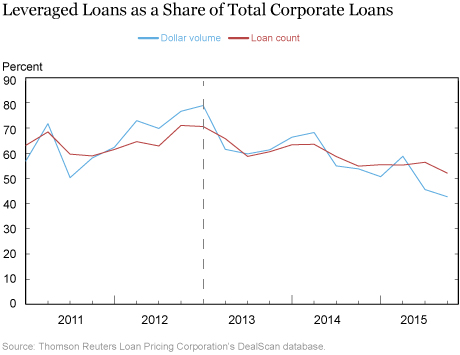

Although the timing of the decline is suggestive, it’s not definitive. It’s possible that the decline in leveraged lending was not actually due to lenders reducing supply, but instead reflected reduced demand for loans. To control for overall loan demand, we scaled the volume of leveraged lending by total corporate lending (as measured by the volume of term loans originated each quarter). The chart below shows that leveraged lending as a share of total corporate lending also declines after the first quarter of 2013, suggesting the decline in leveraged lending does not merely reflect a decline in overall loan demand.

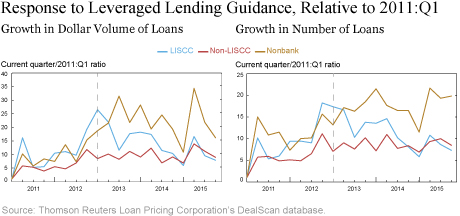

We also examine how different types of lending institutions responded to the leveraged lending guidance. Banks overseen by the Large Institution Supervision Coordinating Committee (LISCC)—the institutions that may pose elevated risks to U.S. financial stability—reduced their leveraged lending most aggressively in response to the guidance.

In contrast, nonbanks increased their leveraged lending—even after the first quarter of 2013. The growing difference in leveraged lending between banks and nonbanks reduces concerns that the decline in overall leveraged lending (as illustrated in the first chart of this post) was an artifact of our use of loan spreads to identify leveraged loans. That’s because in the case of an overall decline in loan rates we would have expected a decline in leveraged lending across all lenders.

Takeaways

Even though not all lenders have cut their leveraged lending in response to the regulators’ guidance it appears that key players, such as LISCC banks, have. This reduction in lending, however, did not necessarily result in an equivalent risk reduction because nonbanks increased their borrowing from banks, possibly to finance their growing leveraged lending activity. This evidence highlights an important challenge of macroprudential policies. Since those policies reach beyond individual banks and target risk in the entire banking system, they are more likely to trigger significant responses that may have unintended consequences.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Sooji Kim is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sooji Kim is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Plosser is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Plosser is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Sooji Kim, Matthew Plosser, and João A.C. Santos, “Did the Supervisory Guidance on Leveraged Lending Work?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), May 16, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/05/did-the-supervisory-guidance-on-leveraged-lending-work.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

The graphs report the amount of loans originated each quarter (not the amount of outstanding loans) and as such they are not affected by loans that reach their maturity date.

For the charts titled “Response to Leveraged Lending Guidance,” do you think the best measure of leveraged lending is ratio of total leveraged loans outstanding relative to Q1FY11? This is the y-axis, correct? I’m curious what the graph would look like if it was $ of originated loans on the y-axis, like you have in the first graph. That would help understand to what extent the slight decrease in leveraged loans shown on the last two graphs is a function of loan expiration versus a result of less leveraged loan activity.