In a previous post, we showed how market rates on U.S. Treasuries violate the expectations hypothesis because of time-varying risk premia. In this post, we provide evidence that term structure models have outperformed direct market-based measures in forecasting interest rates. This suggests that term structure models can play a role in long-run planning for public policy objectives such as assessing the viability of Social Security.

Motivation

The future evolution of interest rates is an important consideration for policymakers. For example, Social Security maintains a trust fund of U.S. Treasury securities to fund future obligations. Consequently, assessing the program’s viability over time must include a view about future interest rates. Moreover, the present-discounted value of the actuarial shortfall depends on the interest rates used for discounting. Small changes in the forecasted path of interest rates can substantially alter the picture of the fund’s financial health. Thus, if the latest forecast has higher rates than previously predicted, Social Security’s expected future revenue would be higher (when the trust fund is positive), and the present discounted cost of any shortfall would be less. Such adjustments can improve perceptions of the program’s sustainability.

Given the pivotal role of interest rate forecasts, it is important to ask how they should be formed. One way is to use term structure models. Term structure models explicitly model the dynamic path of interest rates and term premia. As we explained in our previous post, term premia compensate investors for bearing interest rate risk. Term premia also vary over time, reflecting the changing magnitude of investor compensation for those risks. As a result, the presence of term premia confounds the inferences that one might make about the market-implied expectation for the path of interest rates when looking at current rates. Term structure models allow analysts to decompose observed interest rates into the expected path of short-term interest rates over the life of the bond and the term premium. We show below that long-run interest rate forecasts based on term structure models are more accurate than commonly used alternatives in an out-of-sample forecasting contest.

The “Horse Race”

We compare the forecasting accuracy of our term structure model against two benchmarks. The first is a “random walk” forecast, which is measured as the average end-of-month yield over the past year of the maturity we are forecasting. This forecast is motivated by the idea that if yields follow a random walk, the best forecast is simply current yields. The second is the forward interest rate, the implied yield on a future bond that equalizes cash flows from purchasing current bonds at different maturities. Using forward rates as a forecast is motivated by the expectations hypothesis that forward rates are unbiased forecasts of future short term rates (see our previous blog post).

We compare these two forecasts against two forecasts produced by the Adrian, Crump, and Moench (ACM) term structure model. To assess the forecasting performance over the longest out-of-sample period, we use a two-factor variant of the model. The first forecast, the “ACM Forecast,” is the model’s “best guess” of the level of interest rates at a specified future time. This forecast naturally embeds a forecast for the level of the term premia at that future time. The second forecast, the “ACM Risk-Adjusted Forecast,” treats the future term premium as zero.

Armed with these four methods, we compare out-of-sample forecasts over this period. By “out-of-sample forecast” we mean that only information available at the time the forecast is made is used. This approach corresponds to the way that forecasts are formed in practice. We forecast the yields on five- and ten-year Treasury bonds over ten- and twenty-year horizons. The ten-year bond approximates the returns from the special issue bonds held by the Social Security trust fund. We use monthly zero-coupon U.S. Treasury yield data from June 1961 to January 2016 (publicly available from the Federal Reserve Board). We use a twenty-five-year “learning period” to calibrate the model. Thus we don’t start forming forecasts using ACM until 1986 so that the model has sufficient data for estimation and each ACM estimate is based on data from 1961 to ten or twenty years before the forecast target.

The Results

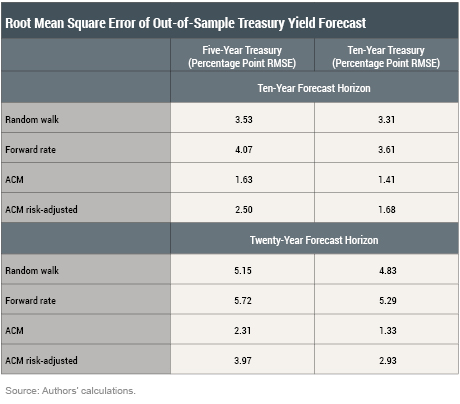

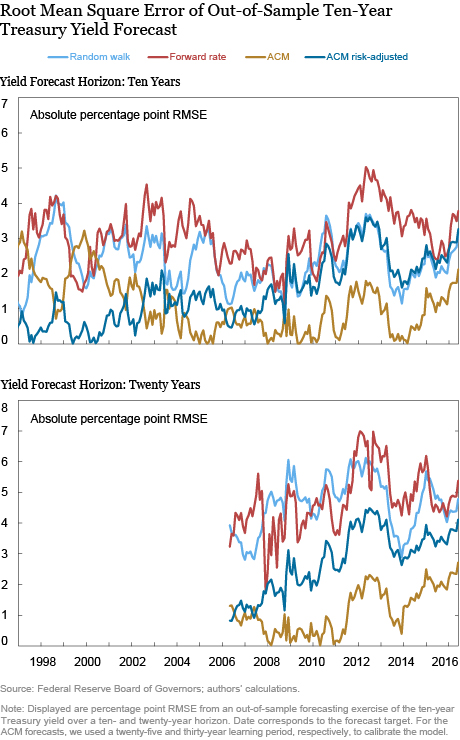

The table below shows root mean square forecasting errors (RMSE) calculated over the period when all four forecasts are available. Root mean square errors are common metrics of accuracy and are defined as the square root of the sum of squared errors; a smaller RMSE means a better forecast. The first thing to notice is that, perhaps unsurprisingly, predicting yields at a longer horizon is generally less accurate. More important, both ACM model-based forecasts soundly beat the two alternatives by as much as 3 percentage points and never less than 1 percentage point. The forward rate performs least well of the four methods. The dynamics of the forecast errors are shown in the charts below, which demonstrate that ACM model-based forecasts often beat the alternatives across time.

Are We Cherry Picking?

Astute observers would caution that the data range we use for calibrating the ACM model is selected arbitrarily. In fact, the choice of a 1961-2016 data range simply reflects the data available to us. Still, that fact leaves open the possibility of a different outcome over different periods. It might be that the forecasting advantage of a term structure model holds for earlier periods, but changes in the economic or monetary policy environment may fundamentally alter the behavior of U.S. Treasury yields in the future.

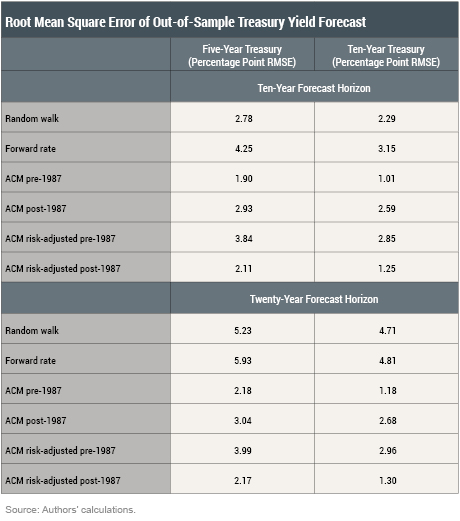

To address that concern, we divided the sample based on economic and policy changes and ran the forecasting race for sub-periods. Since monetary policy is a significant determinant of interest rates, we divide the data into two periods: 1961-1987 and 1987-2006. The earlier period was characterized by high and variable inflation and Treasury yields. But the year 1987, when Alan Greenspan became the chairman of the Federal Reserve, marked the start of the so-called “Great Moderation,” a period defined by lower, more stable inflation and a steady fall in Treasury yields. These two periods reflect an economically meaningful partition of the data.

For this subperiod horse race, we first estimate ACM parameters using data only from 1961 to 1987 or only from 1987 to 2006, and then forecast yields between 2006 and 2016 using the four forecasts described in the previous section. The table below displays the RMSEs from the subperiod exercise. Overall, these results confirm our main finding that forecasts from the ACM term structure model are more accurate than the alternatives. Interestingly, the ACM Forecasts do better with the pre-1987 parameters, but the ACM Risk-Adjusted Forecasts do better using the post-1987 parameters. One possible explanation is that the Risk-Adjusted Forecast coincides more closely with the low, near-zero risk premia prevailing since 2006.

Going Forward

Although bond yields embed general expectations about future interest rates, they also reflect the compensation investors demand for bearing interest rate risk. Our forecasting horse race shows that interest rate forecasts based on term structure models outperform two common market-based alternatives. These results bolster evidence that risk premia are not constant, but instead vary over time with the economic and policy environment. Our exercise suggests that term structure models can in fact play a useful role in long-run financial planning.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is a senior vice president and the associate director of research for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Richard K. Crump is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Peter A. Diamond is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and a former resident scholar in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rui Yu is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Tobias Adrian, Richard K. Crump, Peter A. Diamond, and Rui Yu, “Forecasting Interest Rates over the Long Run,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), July 18, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/07/forecasting-interest-rates-over-the-long-run.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Excellent and convincing post, especially for those who are already using intensively the ACM model (not only for US Treasuries). Yet I have a question. Since the statistical model is designed to estimate risk-adjusted forward rates, term premia are actually residuals.Therefore, while I understand how the model can be used to extract the unbiased long term (for instance 10 in 10) risk adjusted rate, I don’t see how it can estimate the term premium at that time horizon. By ‘naturally’, do the authors refer to a long term average of the term premium, or the latest value, or something else I may have missed?