Jason Bram and Joelle Scally

The 9/11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center left a deep scar on New York City and the nation, most particularly in terms of the human toll. In addition to the lives lost and widespread health problems suffered by many others—in particular by first responders and recovery workers—the destruction of billions of dollars’ worth of property and infrastructure led to severe disruptions to the local economy. Nowhere were these disruptions more severe and long-lasting than in the neighborhoods closest to Ground Zero.

Looking back fifteen years, it seems abundantly clear that although the city’s economy was indeed thrown off its growth track for a while, it eventually rebounded strongly, as has been noted in many studies. In 2002, we assessed both the short-term economic effect and the likely longer-term effect of the attack. Our follow-up studies in 2003 and 2006 reassessed the economic effect, based on more complete data. Outside studies have examined in more detail the ramifications for Lower Manhattan and Chinatown. In this post, we review a few metrics pertaining to Lower Manhattan, which was most severely affected in the immediate aftermath of the attack.

For at least a year following 9/11, New York City employment was depressed, particularly in areas close to Ground Zero. Various studies show there was a disproportionate impact upon areas of Manhattan south of 14th Street—especially south of Canal Street, which includes most of Chinatown. And many of those areas were slow to recover. But recover they did—in terms of not only population but also employment, real estate values, and other metrics. To illustrate just how resilient disaster-stricken economies can be, we will focus on population and employment. Let’s first briefly review the performance of New York City as a whole.

The City’s Rebound

New York City’s economy was slow to get going in 2002 and 2003. The economy had been buffeted by not only the terror attack but also the bursting of the dotcom bubble and a national recession that started well before 9/11. In fact, it took roughly five years for employment in the Big Apple to get back to the peak seen in 2000. Yet, by 2006, the city was growing at a fairly good clip. In every year since, job growth has been stronger in New York City than in the rest of the nation—an unprecedented development for a city whose job growth had historically lagged the nation’s consistently by 2 to 3 percentage points over the years. Even during the Great Recession, when the city’s key securities industry shed tens of thousands of jobs, job losses were milder in New York City than nationwide. But what about Lower Manhattan—the area around the site of the attack?

Lower Manhattan’s Rebound

Clearly two basic indicators of a neighborhood’s vitality are residents and jobs. Insofar as population goes, strong trends had already been underway as lower Manhattan transitioned from a mostly commercial area to more of a residential-commercial blend. This trend was epitomized by the widespread conversion of office buildings into apartment buildings and the expansion of Battery Park City. In the weeks after 9/11, there were several news stories about area residents deciding to move out of Lower Manhattan, for fear of future terror attacks. At that time, many parts of downtown were not very livable: subway service was reduced, street access was limited, and noise and air pollution were a key concern.

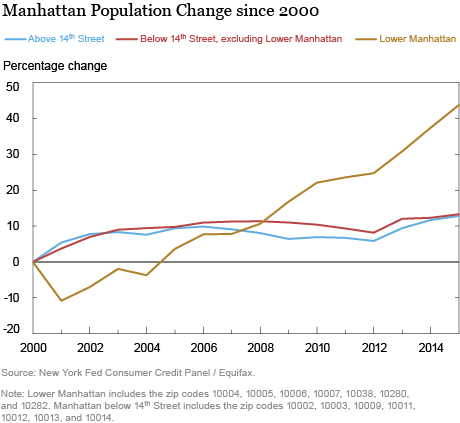

So what ended up happening? To find out, we examined the adult populations in our Consumer Credit Panel, which is based on Equifax credit report data. We grouped individuals by their zip codes into three zones: 1) Lower Manhattan immediately surrounding the World Trade Center, 2) Manhattan below 14th Street, and 3) Manhattan above 14th Street. As it turns out, the population residing in Lower Manhattan fell by about 11 percent in 2001, with almost all zip codes seeing declines. In 2002 and 2003, however, the population of Lower Manhattan rebounded, almost fully returning to pre-attack levels. By 2005, downtown’s population reached a new high, and it has expanded briskly in almost every year since. By 2014, Lower Manhattan’s population was roughly 40 percent higher than where it stood before the attack.

Further, the Consumer Credit Panel indicates that the population of Lower Manhattan has not only burgeoned but, on average, it has also gotten considerably younger. In contrast, the population in Manhattan above 14th Street, as well as in the outer boroughs, has gotten a bit older.

The rebound in jobs came more slowly and has not been quite as dramatic. Even within New York City, many thousands of jobs moved from downtown to Midtown. According to the Census Bureau, between 2000 and 2003, the number of employees at businesses in the zip codes south of Canal Street tumbled by 17 percent. By 2014, employment had rebounded quite a bit, but still not to pre-attack levels. But keep in mind that in 2000, more than 10 percent of Lower Manhattan employees worked in the World Trade Center, which had its own zip code. Excluding that one zip code, Lower Manhattan employment rose nearly 10 percent from 2000 to 2014, the latest year for which employment data are available by zip code.

But what’s happened since 2014? Well, anecdotally, the opening of One World Trade Center in late 2014 brought thousands of jobs to Lower Manhattan by 2015 and still more in 2016. With roughly 2.6 million square feet of office space and 55,000 square feet of retail space, the mostly leased building can be expected to house well over 10,000 jobs. Also opened at the same time, the Fulton Center transit hub has not just facilitated transit links, but also includes a number of retail establishments with hundreds of jobs.

How was this neighborhood able to not only rebound but thrive? Clearly, state- and city-financed tax incentives—combined with a temporary swoon in rents—made the neighborhood increasingly affordable. Federal aid helped the city rebuild and modernize much of its destroyed and damaged infrastructure, and also invest in new infrastructure. And the area’s central location—which offers access to numerous subway lines, as well as PATH train and ferry service to New Jersey—remained a major asset after the attack, even though many of the transportation links remained disrupted for many months. What has also helped is what hasn’t happened. Although more Wall Street investment firms are now located in Midtown Manhattan than on Wall Street—or in Lower Manhattan for that matter—many still remain downtown. And, of course, our own institution, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as well as the New York Stock Exchange, have not gone anywhere.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jason Bram is a research officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Jason Bram and Joelle Scally, “Lower Manhattan since 9/11: A Study in Resilience” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 19, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/10/lower-manhattan-since-911-a-study-in-resilience.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics