Japan offers a preview of future U.S. demographic trends, having already seen a large increase in the population over 65. So, how has the Japanese economy dealt with this change? A look at the data shows that women of all ages have been pulled into the labor force and that more people are working longer. This transformation of the work force has not been enough to prevent a very tight labor market in a slowly growing economy, and it may help explain why inflation remains minimal. Namely, wages are not responding as much as they might to the tight labor market because women and older workers tend to have lower bargaining power than prime-age males.

Demographics Matter

People commonly express a very grim opinion of the Japanese economy, with the country’s output growing at an average rate of only 0.5 percent per year over the past ten years. A factor often not considered is that, for all its bad press, Japan’s per capita output growth has almost matched that of the United States since 2000. So, it would seem that the perception of Japan having a feeble economy is in part due to demographic rather than economic reasons. This shift will be increasingly important in considering future growth since Japan’s population is set, according to the United Nations (UN), to fall at a 0.25 percent rate over the next five years, a faster decline than the 0.10 percent rate in the last five years.

A second demographic factor to consider is that the prime-age share of the population (15–64 years of age) has been shrinking. UN data have the percent of the population that is prime age falling from 66 percent in 2005 to 61 percent just ten years later. The forecast is that it will fall to 58 percent in the next ten years. For comparison, the U.S. share fell slightly from 68 percent in 2005 to 67 percent in 2015. It is projected to fall to 64 percent by 2025.

Making Up for a Shrinking Working-Age Population

Japan’s labor force (those with jobs and those looking for one) has, like the size of the population, been relatively unchanged over the past ten years. The graying of the population, however, has had a big impact on the composition. The prime-age part of the labor force has been falling at a 0.5 percent rate, reflecting the men’s side falling at almost a 1 percent rate and the female labor force staying largely unchanged. The 65 and older group in the labor force has been growing at a 4 percent rate over this period.

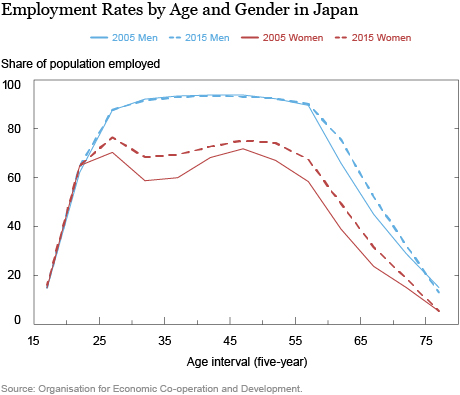

The chart below shows employment rates by age group for men and women for 2005 and 2015, that is, the percent of the population, by sex and age cohort, that is employed. The data reveal a substantial increase in employment rates for those over 60 years of age and for working-age women. So, the economy responded to the drop in the number of prime-age males by absorbing more women and older people into the workplace.

The altered demographic composition is also reflected in the greater share of employees that are short-term or part-time workers. These arrangements now make up 24 percent of all jobs, up from 21 percent ten years ago. As could be expected, the increases in this category of workers are attributable to prime-age women (who comprise 42 percent of the increase) and those over 65 years of age (who make up 47 percent of the increase).

Demographics and Wages

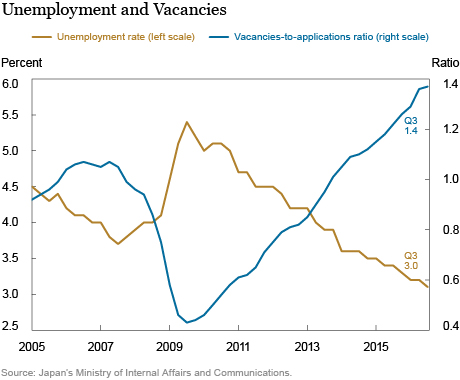

A changing workforce may be one of the reasons that Japanese inflation has not picked up in recent years despite the tight labor market. The extent of this tightness can be seen in the next chart, with the unemployment rate down to 3.0 percent, below the ten-year average of 4.2 percent. In addition, there are 1.4 vacancies for each job application. This ratio last hit this high level in 1991 and has averaged 0.9 vacancies over the past twenty years.

The Bank of Japan started its asset purchase program in April 2013 in order to stimulate the economy and increase the country’s inflation rate. It had projected that inflation would reach 2.0 percent by 2016, but its September 2016 policy assessment acknowledged that it has not reached its goal, attributing it to the failure of inflation expectations to rise.

One can argue that another factor restraining inflation is the significant demographic changes that have affected the bargaining power of the average worker. More women and more older workers entering the job market, with many working part-time and temporary jobs, has had a depressing impact on wages since these cohorts tend to have less bargaining power than males with regular jobs. Indeed, two recent Liberty Street Economics blog posts support this contention with evidence that the aging of the U.S. labor force is putting downward pressure on real wages. In particular, they find that as the labor force ages,

more workers transition from the fast to the slow or negative real‑wage‑growth phases of their careers.

The failure of inflation expectations to rise is making it harder for the Bank of Japan to reach its inflation goal. Another potential consideration is that the very tight labor market is giving less of a boost to prices than might have been expected because of the dramatic transformation of the labor force in recent years.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Bianca De Paoli is a senior economist in Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Harry Wheeler is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Bianca De Paoli, Thomas Klitgaard, and Harry Wheeler, “Inflation and Japan’s Ever-Tightening Labor Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), November, 14, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/11/inflation-and-japans-ever-tightening-labor-market.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

What I found when I lived in Japan several years ago showed that it was very difficult, especially for foreigners, to find a job (formal or office job) in Japan, since they had to be fluent (at some level) on Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. Thus, even though Japan offered various jobs to non-Japanese citizens – due to its declining trends on population – However, in my opinion, the government regulation on labor market was too strict that affected the economic growth.

The trend in per capita output growth described here had also been noted by previous Bank of Japan governor Shirakawa, who had argued that many of the policy challenges facing Japan had a basis in structural demographic factors, and therefore that monetary policy was unlikely to be effective in addressing such challenges. Somewhat belatedly, the Kuroda BOJ now appears to be more accepting of this view.