Ever since “regular and predictable” issuance of coupon-bearing Treasury debt became the norm in the 1970s, thirty years has marked the outer boundary of Treasury bond maturities. However, longer-term bonds were not unknown in earlier years. Seven such bonds, including one 40-year bond, were issued between 1955 and 1963. The common thread that binds the seven bonds together was the interest of Treasury debt managers in lengthening the maturity structure of the debt. This post describes the efforts to lengthen debt maturities between 1953 and 1957. A subsequent post will examine the period from 1957 to 1965. An extended version of both posts is available here.

Marketable Debt after World War II

World War II was financed through three primary means: E-bonds bought through payroll savings plans, seven large wartime loan drives, and a Victory Loan drive launched in late 1945. Each of the loan drives offered a long-term bond, but none of the bonds had a maturity longer than twenty-seven years. In mid-1946, the Treasury had $268 billion of debt outstanding, including $190 billion of marketable debt with an average maturity of 10⅓ years.

Between 1946 and 1951, the Treasury conducted virtually all of its financing at the front end of the yield curve. Of fifty-eight marketable coupon-bearing issues sold in those six years, forty-four matured in a year or less. By mid-1952, the average maturity of marketable debt had fallen to 5⅔ years.

An Initial Effort to Extend the Maturity Structure of the Debt

The November 1952 nomination of George Humphrey as Secretary of the Treasury in the incoming Eisenhower administration fueled expectations that the Treasury would soon begin issuing longer-term bonds. The Wall Street Journal reported that Humphrey wanted to “replace a big chunk of the government debt now represented by short-term securities with longer-term bonds.” Oft-cited reasons for the move included reducing the frequency of refunding operations (which had become almost monthly occurrences and were believed to interfere with the timely execution of Federal Reserve monetary policy) and reducing the inflationary implications of a large outstanding stock of liquid short-term securities.

On April 8, 1953, Treasury officials announced preliminary terms for a $1 billion fixed-price cash subscription offering of 3¼ percent 30-year bonds at par, the first long-term marketable bond since the Victory Loan. The New York Times stated that “the new issue is adequate proof . . . that the Eisenhower administration [is] in earnest in its pledge to work for more balance in the public debt structure by . . . putting out securities of longer term.”

Allowing deferred payment of up to 90 percent of the purchase price for as long as three months and bearing a 3¼ percent coupon (yields on outstanding long-term Treasury bonds were then about 3 percent), the new offering was seen as a “sure thing” and likely to trade at a premium of a point or more. Humphrey, concerned about demand from “free-riders”—speculators who subscribed with the intention of selling their awards quickly and pocketing the premium over par—asked banks and other creditors to abstain from financing the 10 percent down payment required at the time a subscription was tendered.

Treasury officials were swamped with $6 billion of tenders when the subscription books opened on April 13. Federal Reserve officials, acting as agents for the Treasury, weeded out $750 million of tenders attributed to free-riders and other speculators and allocated $1.2 billion of bonds among the $5.25 billion of remaining tenders. Subscriptions up to $5,000 were filled in their entirety and larger subscriptions were awarded 20 percent of the amount subscribed, subject to a minimum of $5,000.

Despite the substantial oversubscription, the new bonds traded only a quarter point over par when trading opened on April 15, possibly because many subscribers had “padded” their tenders in anticipation of a low allotment rate. Less than two weeks later, the bonds broke through par. The New York Times attributed the price slide to “the unloading of small aggregates of bonds by speculators disappointed at not having realized a quick profit on a would-be ‘free ride.’”

The disappointing after-market for the 30-year bonds led Treasury officials to throttle back on their maturity extension initiative. The Wall Street Journal reported that officials were debating the idea of “temporarily abandoning . . . the drive to put more of the public debt into long-term securities.” The Treasury did not offer another bond with more than ten years to maturity until February 1955.

A 40-Year Bond

By early 1955, market participants were beginning to think it was time for the Treasury to reenter the long-term bond market. The Wall Street Journal cited “renewed talk of a possible new long-term Treasury issue” and the New York Times reported the belief among government securities dealers that “the market would welcome an additional supply of long-term bonds.”

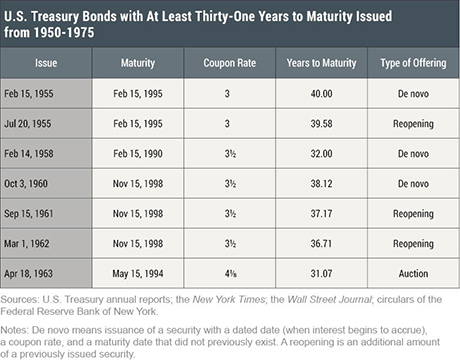

On January 27, Treasury officials announced the offering of a 13-month note and a 40-year bond in a par-for-par exchange for a 2⅞ percent bond called for early redemption on March 15 (see table below). Of the $2.6 billion of the 2⅞ percent bonds outstanding, $323 million was exchanged into the 13-month note, $1.9 billion was exchanged into the 40-year bond, and $365 million was held back for cash redemption. Treasury officials called the offering “a complete success” and Secretary Humphrey expressed his satisfaction with the “successful placing” of the issue. Officials said that, going forward, they expected to offer a long-term bond “once or twice a year.”

In fact, not four months had passed before rumors began to circulate that the Treasury was contemplating another long-term issue. Officials confirmed the rumors on July 5, announcing that they would reopen the 40-year bond in a $750 million fixed-price cash subscription offering.

Unlike the 30-year bonds sold for cash in 1953, the new offering was carefully targeted to “savings-type investors” such as pension and retirement funds. The targeting took two forms. First, savings-type investors were permitted to pay for their allotments on an installment basis—with as little as 25 percent of what they owed required on the scheduled settlement date of July 20 if they agreed to pay at least 60 percent by September 1 and the balance by October 3. Second, the Treasury announced that it was prepared to “make different percentage allotments . . . to avoid excessive allotments of bonds to non-savings-type investors.”

Three days after the close of the subscription books, the Treasury announced that it had received $1.7 billion of tenders, including $747 million from savings-type investors. Subscriptions for less than $25,000 were filled in their entirety, larger subscriptions from savings-type investors were allotted 65 percent of the amount subscribed (subject to a minimum of $25,000), and all other subscriptions were allotted 30 percent (subject to the same minimum).

The Failure of Humphrey’s Maturity Extension Program

Notwithstanding the success of the 40-year offerings, Humphrey did not bring another long-term offering before leaving office in mid-1957. The average maturity of marketable debt was 5⅔ years in mid-1952 and 4¾ years in mid-1957. Humphrey explained the collapse of the stretch-out program by saying that “there’s no market for long-term bonds at interest rates we’d like or ought to pay” and claimed that the government could not sell five-year bonds “at any price.”

Humphrey made the mistake of thinking that he could foster maturity extension by offering debt with as long a maturity as possible whenever possible. However, that essentially ad hoc approach proved ineffective and inefficient within the context of a debt management architecture founded on fixed-price (rather than auction) offerings of coupon-bearing debt, because Treasury officials were only occasionally willing to offer long-term securities that were competitive with private sector offerings. The resulting sporadic issuance left market participants uncertain of when the next long-term offering might come and thus provided little incentive to plan for that next offering. As a result, long-term offerings during Secretary Humphrey’s tenure tended to be small as well as sporadic.

Sporadic issuance also meant that officials rarely had a firm grasp on where to price a long-term bond. Too high a yield was liable to attract intense speculative interest; too low a yield might fail to attract sufficient interest of any kind. Fearing the repercussions of a failed offering, debt managers commonly underpriced longer-term issues and sought to limit speculative participation with stop-gap measures, such as asking Federal Reserve Banks to weed out subscriptions from speculators, providing preferential payment terms for savings-type investors, and awarding larger allotments to savings-type investors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Kenneth D. Garbade is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Kenneth D. Garbade, “Beyond 30: Long-Term Treasury Bond Issuance from 1953 to 1957,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 6, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/02/beyond-30-long-term-treasury-bond-issuance-from-1953-to-1957.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics