Most people find themselves looking for work at some point in their adult lives. But what brings employers and job seekers together? And does searching for a new job while unemployed lead to different outcomes than searching while employed? Little is known about the job search process for unemployed workers. Even less is known about the search process and outcomes for currently employed workers—so‑called “on‑the‑job” search. This Liberty Street Economics post aims to shed light on these questions and to draw some conclusions for our understanding of labor market dynamics more generally.

The New York Fed has been fielding a labor market supplement to its Survey of Consumer Expectations every October since 2013. The supplement focuses on the job search process for all individuals, regardless of their employment status. The questions cover search behavior (for instance, what methods respondents used to look for jobs, the time spent searching for work, the number and type of contacts with employers, and job interviews), as well as the nature, number, and characteristics of any job offers received. Pooling together three successive waves of the survey supplement yields data on about 2,300 employed workers, 165 unemployed workers, and 430 respondents who are classified as being out of the labor force, all between eighteen and sixty-four years of age. Labor force status is defined using the Bureau of Labor Statistics definition: Specifically, individuals are classified as unemployed if they are not currently employed, actively looked for work in the last four weeks, and are available to start work within the next seven days. Workers on temporary layoff are also classified as unemployed.

How Do People Look for Jobs?

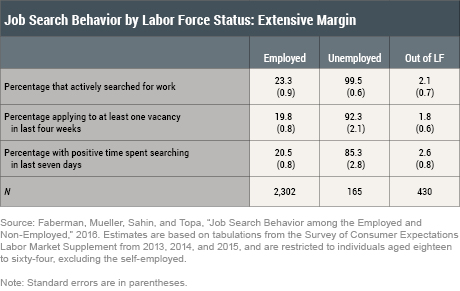

The table below describes the “extensive margin” of job search, by labor force status: That is, how many people actively searched for work in the last four weeks, regardless of how much effort they put into it. We employ various definitions to measure active search. The first definition is based on whether respondents report having used at least one job search method out of a comprehensive list of possible methods, which includes applying for jobs, looking at job postings online or elsewhere, sending out resumes, and contacting employers, employment agencies, former coworkers, or other professional contacts. The second definition focuses on those who applied to at least one job posting. The final definition is a measure based on whether respondents spent any time searching for jobs in the last seven days.

The most surprising finding is that search is common among employed workers. Depending on the specific measure used, roughly one in five or one in four employed workers actively looked for work during the four weeks preceding the survey. Almost all of the unemployed actively searched—a predictable finding, given the definition of unemployment. (The only exceptions come from those on temporary layoff.) A small fraction of respondents who were not in the labor force also searched. These are respondents who searched but were not available to start work in the next seven days and were therefore classified as out of the labor force.

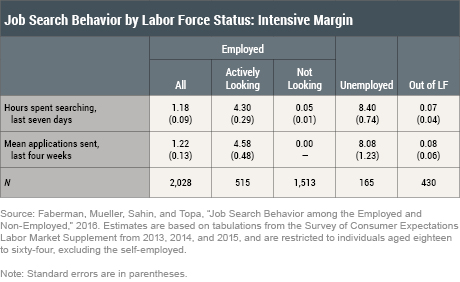

Let us now turn to the “intensive margin” of job search: Conditional on having actively searched, how intensively did people in our survey look for jobs? Here we employ two measures: one is a measure of hours spent searching in the last seven days; the other is the number of job applications sent out (either online or through other means) in the last four weeks. We also further distinguish the employed by their “extensive margin”—that is, by whether or not they are actively looking for work. The table below reports the results. The main finding is that unemployed job seekers search harder than the employed. On average, the unemployed spend 8.4 hours per week searching, compared with 1.2 hours for the employed, and send out 8.1 applications per month, compared with 1.2 for the employed. If we focus on employed workers actively looking for work, we find that their search effort is still only about half that of the unemployed.

What Works?

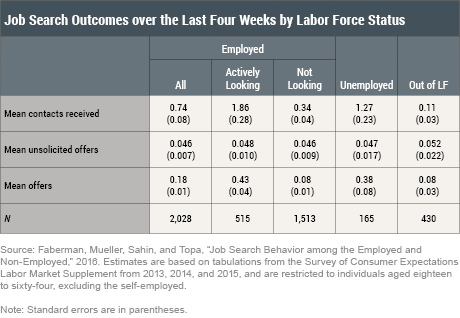

So far, we have focused on what people do to look for work. But how effective is their search? To answer this question, we have to look at the outcomes of their efforts. Here we consider two measures, both computed over the preceding four weeks: the number of employers who contacted our respondents about a job opening, and the number of actual job offers received. We can summarize the results as follows (see the table below): First, even though unemployed workers search about seven times as hard as the employed (as illustrated in the table just above), they only generate about twice the number of offers. Thus, searching while unemployed is much less effective in generating offers than searching while on the job. Second, employed workers actively looking for work receive the greatest number of employer contacts and job offers. So, again, searching while employed seems to have the highest return in terms of generating new offers. Third, even those employed workers who are not looking for new work receive a substantial number of employer contacts and offers. This finding illustrates the importance of informal contacts and recruiting. Informal contacts can include networking at industry events; conversations with friends, present or former coworkers, or business associates; and unsolicited contacts by employers, recruiters, or headhunters.

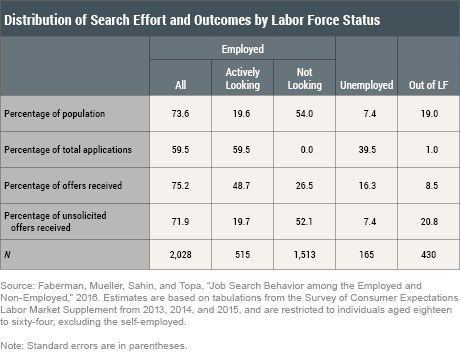

These results are summarized in a slightly different way in the table below. Unemployed workers make up about 7 percent of our sample. They send out 40 percent of the total applications in the sample, but receive only about 16 percent of the total offers. By comparison, those employed and actively looking for work make up about 20 percent of the sample but receive almost half of all offers. Further, the employed not looking for work receive about one‑fourth of all the offers in our sample—more than the unemployed! They also receive more than half of all the unsolicited offers in our sample. These findings again point to the importance of informal contacts and recruiting in labor market churning.

Conclusion

We have found that “on‑the‑job” search is common among employed workers, and that the job search process is more effective for currently employed workers than for the unemployed. In the paper cited as the source of our table estimates, we also show that offers received by employed workers are better than those received by the unemployed, both in terms of the wage associated with them and in terms of their nonwage benefits. This is true even after controlling for detailed worker characteristics and prior work history.

What are the broader implications of these findings for our understanding of labor market dynamics? We know that job-to-job transitions are an important component of new hires, and an important driver of wage growth in the economy. Voluntary quits (typically followed by a transition to a new job) have been described by Chair Janet Yellen as an important marker of the health of the labor market. By highlighting the importance and pervasiveness of on‑the‑job search, we have provided some evidence on the search mechanisms that underlie voluntary quits and job‑to‑job transitions. By tracking these search processes over time we can gain further insights into the likely evolution of these important labor market markers going forward.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

R. Jason Faberman is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Andreas I. Mueller is an assistant professor of finance and economics at Columbia Business School.

Ayşegül Şahin is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rachel Schuh is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

R. Jason Faberman, Andreas I. Mueller, Ayşegül Şahin, Rachel Schuh, and Giorgio Topa, “How Do People Find Jobs?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), April 5, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/04/how-do-people-find-jobs.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics