A major question facing policymakers is how to deal with slumps in bank credit. The policy prescriptions are very different depending on whether the decline is a result of global forces, domestic demand, or supply problems in a particular banking system. We present findings from new research that exactly decompose the growth in banks’ aggregate foreign credit into these three factors. Using global banking data for the period 2000-16, we uncover some striking patterns in bilateral credit relationships between consolidated banking systems and borrowers in more than 200 countries. The most important we term the “Anna Karenina Principle” of global banking: all healthy credit relationships behave alike; each unhealthy credit relationship is unhealthy in its own way.

We find that during noncrisis periods, bank flows are well-explained by global factors and local demand. But during crisis periods aggregate and country-specific credit flows are largely determined by idiosyncratic “granular” factors that represent the enormous heterogeneity in the shocks that hit creditor banking systems and borrower countries. This finding has important implications for why standard econometric models break down during crises. Flows that are predicated on common determinants of credit growth work well in “normal” times but not in crisis times.

The Data

Our analysis relies on the Consolidated Banking Statistics (CBS) reported to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). These statistics capture the consolidated foreign claims (that is, loans, holdings of securities, and other financial claims) of banks headquartered in 31 reporting countries on counterparties in more than 200 countries. We make adjustments to the publicly available data for two reasons: to correct for the substantial measurement error that can arise from methodological changes in reporting (that is, “breaks in series”) and because the exchange rates for the currencies in which the claims were denominated changed.

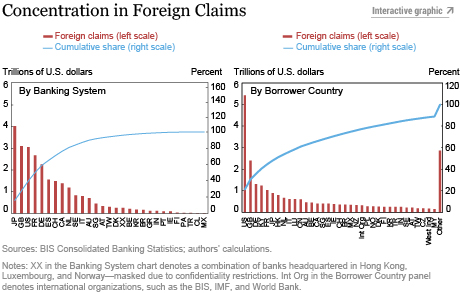

As we can see from the chart below, the data show that banks’ foreign claims are highly concentrated in only a handful of banking systems and a somewhat larger set of counterparty countries. This concentration affects the data in two important ways. First, the vast majority of bilateral credit flows are small compared to the typical banking system, which makes it problematic to use standard regression techniques to infer aggregate behavior (as shown in Amiti and Weinstein, forthcoming). Second, the fact that claims are concentrated in a few large banking systems means that idiosyncratic credit supply shocks in one banking system can have significant aggregate implications. For example, problems in U.S. banks that are not shared by other banking systems can have a global impact, potentially generating credit crunches in countries that rely on these banks.

The Methodology

We use the methodology from Amiti and Weinstein to decompose the growth in banks’ foreign credit into three components: a global common shock, an idiosyncratic supply shock, and an idiosyncratic demand shock. We provide evidence on the validity of these shocks, showing that they move over time in an intuitive way. For example, those banks that reported more losses during the crisis (scaled by their Tier 1 capital) had larger negative supply shocks, which means larger overall contractions in claims on all countries. Similarly, those banking systems with higher pre-crisis deposit to total-liabilities ratios (a proxy for the stability of their funding) experienced less severe negative supply shocks, and correspondingly higher overall growth in claims.

Main Findings

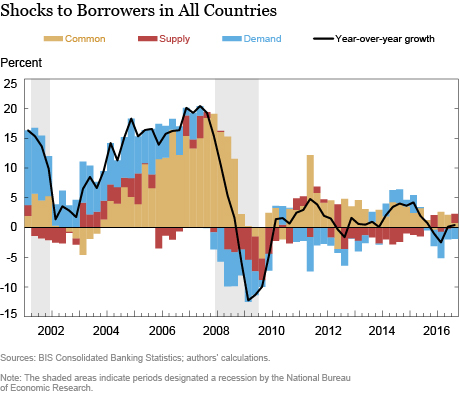

The most notable findings uncovered in our study are shown in the chart below. First, common shocks (gold bars) dominate in periods when the claims of all banking systems on all countries grow at similar rates. During the run up to the global financial crisis (2003-07), nearly all major banking systems expanded credit at similar rates to borrowers in the major counterparty countries.

Second, the common component almost disappeared during the crisis period as credit fluctuations began to be driven largely by the idiosyncratic demand and supply shocks. This suggests that the global contraction in claims was uneven across banking systems and counterparty countries, which illustrates the Anna Karenina Principle. The data militate against a single story that captures all countries’ experiences; idiosyncratic supply and demand factors played important and different roles in each country.

Third, negative idiosyncratic supply shocks (red bars) were largest during the crisis period, providing evidence of a credit crunch in some banking systems affecting the supply of credit to certain borrowers. This is particularly so for emerging European countries, which were most dependent on troubled banks. For example, during the 2007-09 financial crisis, negative granular supply shocks account for much of the decline in borrowing in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland.

Knowing what drives aggregate bank lending is of particular relevance for policymakers. For example, during the Euro sovereign debt crisis, which started in mid-2010 and continued in fits and starts through 2015, we find that negative idiosyncratic supply shocks contributed little to the contraction of foreign claims. The severe downturns in global banks’ claims on the key countries involved in the crisis—Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain—were unique to these countries, and hence registered as negative demand-side shocks. Nevertheless, negative supply shocks did play some role: Banks headquartered in some of these countries saw large contractions in their foreign credit, some of which had been directed to other borrower countries in crisis. This decomposition provides policymakers with invaluable information on the underlying forces of international banking flows.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Mary Amiti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Patrick M. McGuire is head of the International Data Hub at the Bank for International Settlements.

David E. Weinstein is the Carl S. Shoup Professor of the Japanese Economy at Columbia University.

How to cite this blog post:

Mary Amiti, Patrick M. McGuire, and David Weinstein, “What Drives International Bank Credit?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), September 6, 2017, Permalink: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/09/what-drives-international-bank-credit.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics