The Committee on the Global Financial System, made up of senior officials from central banks around the world and chaired by New York Fed President William Dudley, recently released a report on “Structural Changes in Banking after the Crisis.” The report includes findings from a wide-ranging study documenting the significant structural adjustments in banking systems around the world in response to regulatory, technological, and market changes after the crisis, while also assessing their implications for financial stability, credit provision, and capital markets activity. It includes a new banking database spanning over twenty-one countries from 2000 to 2016 that could serve as a valuable reference for further analysis. Overall, the study concludes that the changed regulatory and market environment since the crisis has led banks to alter their business models and balance sheets in ways that make them more resilient but also less profitable, while continuing their role as intermediaries providing financial services to the real economy.

Business Model Developments

The report highlights how banks in advanced economies are reorienting their business models away from relatively complex activities such as trading and market-making back toward more traditional activities like lending and deposit-taking. Large European and U.S. banks have also become more selective and focused in their international banking activities—with some European banking systems showing a sizeable reduction in foreign lending, while banks from the large emerging market economies (EMEs) and countries less affected by the crisis have in fact expanded internationally.

Balance Sheets and Risk Profiles

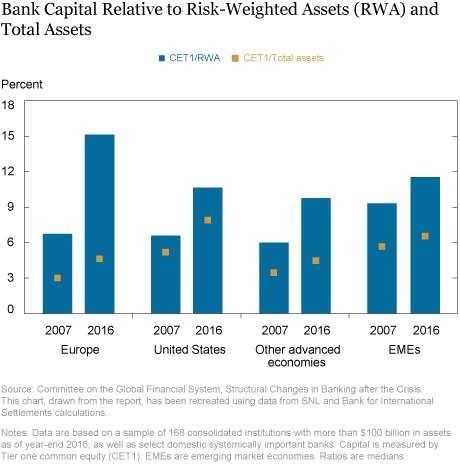

Banks globally have substantially increased their capital (see the chart below) and liquidity buffers, and shifted toward more stable funding sources. Healthier balance sheets coupled with the increased use of stress testing by banks and supervisors have further enhanced bank resilience to future shocks. Qualitative evidence gathered for the report suggests that banks have also considerably strengthened their risk management practices, though most supervisors see room for improvement.

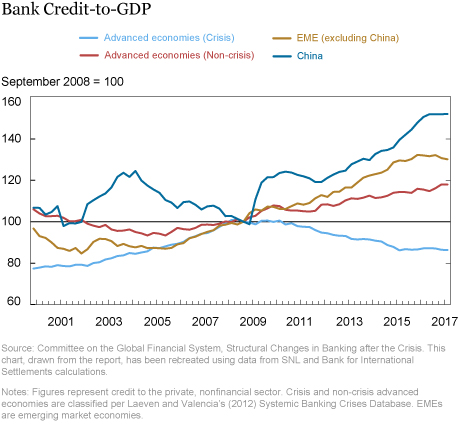

There is also evidence that bank lenders have become more risk-sensitive and more discriminating across borrowers, in line with the objectives of regulatory reform. That said, the report does not suggest a systematic change in the willingness of banks to lend locally, despite uneven credit growth across countries. For advanced economy countries whose banking systems were hit hard by the crisis, bank credit contraction relative to GDP ended only around 2015 and has stabilized since (see the next chart). By comparison, in advanced economies not significantly affected by the crisis, bank credit continued to grow solidly, notwithstanding tighter regulations. Over the same period, bank lending has expanded strongly in EMEs, raising sustainability concerns and prompting policy responses such as tighter loan-to-value limits in some countries.

Profitability

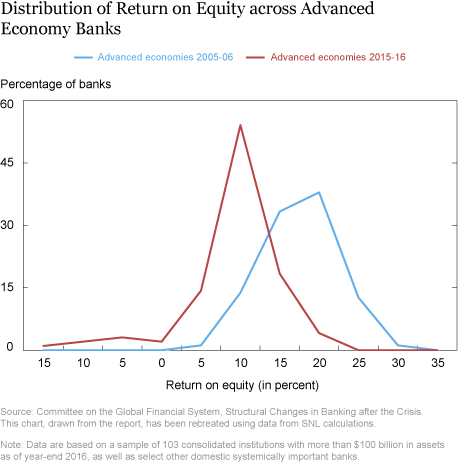

Though the change in business models, risk profiles, and balance sheets should make banks more resilient, they may also dampen profitability. As shown in the chart below, the distribution of return on equity (ROE) across the advanced economy banks studied in the report has shifted significantly leftward in 2015-16 when compared to 2005-06, the period just before the crisis, while the median RoE has declined 8 percentage points to 7 percent over the same period. This shift partly reflects the higher equity base required by reformed capital standards, but also sluggish revenue growth (due in part to lower risk-taking) and high costs, including “legacy” costs from past investment decisions and, in some cases, misconduct. Simulations in the report suggest the need for further cost-cutting and structural adjustments to restore profitability towards levels currently required by bank investors, particularly for banks in some European countries.

The report concludes with three messages for policymakers, supervisors, and market participants:

- While a stronger banking sector has resumed supplying intermediation services to the real economy since the crisis, policymakers should remain attentive to potential unintended gaps in credit supply and services as banks change their risk profiles in response to the new regulatory regime and post-crisis market environment. Moreover, the shift by some banks away from capital market activities has coincided with signs of illiquidity in some markets, although causality remains an open question.

- Banks and supervisors need to remain attentive to problems arising from lower profitablity, if sustained over the long term. Supervisory vigilance is required as banks adapt to an environment of softer profitability given that could entail further cost-cutting through cutbacks in critical functions and services, or the adoption of riskier business models. Where weak profitability signals the existence of excess capacity and where there are structural impediments to exit for individual banks, authorities can facilitate adjustment of the banking sector.

- Lastly, if lower profitability represents the “new normal,” banks and their investors may need to adjust their profitability expectations accordingly by taking into account the structural and regulatory changes since the crisis that make banks more resilient, and presumably their shares less risky to invest in.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Nicola Cetorelli is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

B. Gerard Dages is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Executive Office.

B. Gerard Dages is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Executive Office.

Paul Licari is a financial analysis associate in the Bank’s Supervision Group.

Paul Licari is a financial analysis associate in the Bank’s Supervision Group.

Afshin Taber is an assistant vice president for financial analysis in the Bank’s Supervision Group.

Afshin Taber is an assistant vice president for financial analysis in the Bank’s Supervision Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Nicola Cetorelli, B. Gerard Dages, Paul Licari, and Afshin Taber, “New Report Assesses Structural Changes in Global Banking,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 2, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/02/new-report-assesses-structural-changes-in-global-banking.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

“resumed supplying intermediation” How so? DFIs always create new money whenever they lend/invest with the non-bank private sector. DFIs pay for their new earning assets with new money. All savings originate within the framework of the payment’s system. Saver-holders never transfer their savings outside of the system unless they hoard currency or convert to other national currencies. \ But the only way to activate said savings is for the saver-holder to invest/spend directly or indirectly (e.g., a non-bank conduit). All bank-held savings are thus un-used and un-spent. This is the sole source of both stagflation (from 1965 – 19810) and secular strangulation (from 1981 to the present).