One goal of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 was to end “too big to fail.” Toward that goal, the Act required systemically important financial institutions to submit detailed plans for an orderly resolution (“living wills”) and authorized the FDIC to create an alternative resolution procedure. In response, the FDIC has developed a “single point of entry” (SPOE) strategy, under which healthy parent companies bear the losses of their failing subsidiaries. Since SPOE makes the parent company responsible for subsidiaries’ losses, we would expect that parents have become riskier, relative to their subsidiaries, since the announcement of the SPOE strategy in December 2013. Do bond raters and investors share this view?

SPOE through the Lenses of Rating Agencies

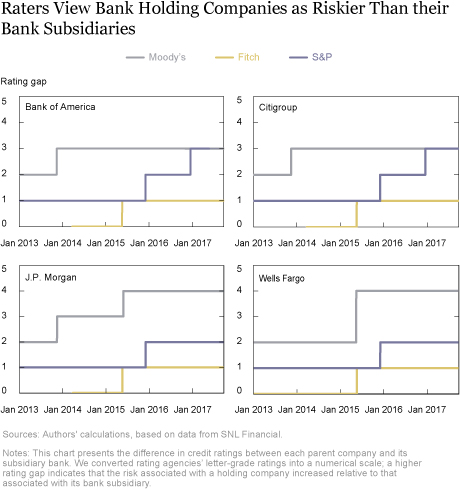

Below we plot the gap in ratings (parent minus subsidiary) by Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) for the four largest bank holding companies (BHC) by assets.

The rating gap has widened for all four banks at all three rating agencies, suggesting raters perceive that SPOE has increased the risk of the parent relative to that of its subsidiary bank. This widening gap coincides with announcements by Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P that SPOE has reduced the expectation of government support for these four BHCs in the event of failure.

Do Financial Markets Share Rating Agencies’ Views?

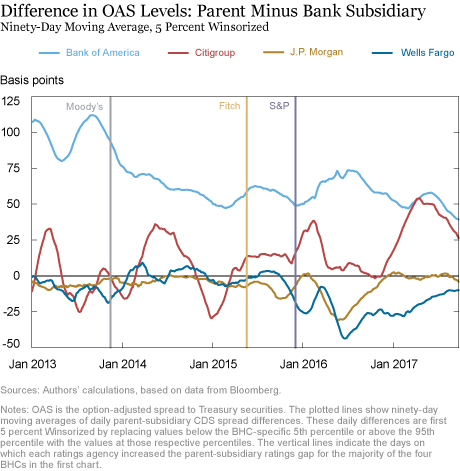

To answer that question, we first look at how spreads have evolved for a matched pair of bonds—one issued by the parent and one by its bank subsidiary. If bond investors agree that SPOE has made the parent riskier, we should see the parent’s option-adjusted spread (OAS) widen relative to that of the subsidiary bank. Contrary to our hypothesis, and the views of rating agencies, the chart below shows that the spread gap has not widened consistently for three of the four holding companies; for the fourth, Bank of America, it has actually narrowed. Nor did the difference in spreads widen noticeably after each of the agencies started to increase the rating gap between parent companies and their bank subsidiaries (points in time marked by vertical lines).

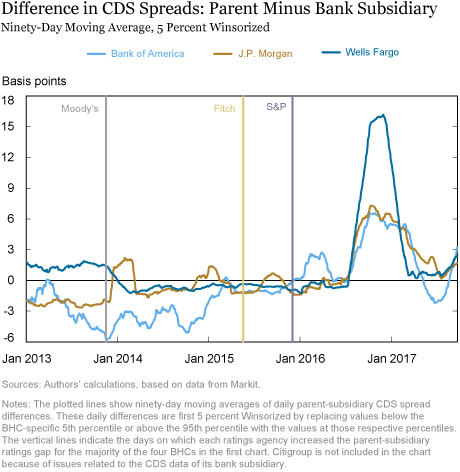

This finding might reflect certain frictions in the bond market—illiquidity or market segmentation, for example. However, we also observe a similar result in the credit default swap (CDS) market, as reflected in the chart below. The difference in CDS spreads (parent minus subsidiary) has not increased persistently since the SPOE was announced. A temporary increase in this difference emerged in July 2016, but that gap has since closed. Overall, we do not see the kind of persistent increase in the difference in spreads that would support the rating agencies’ view that parent companies have become riskier relative to their subsidiaries.

Did the Dodd-Frank Act end “too big to fail”? In a pair of blog posts published in 2015, we argued that, at the time, bond and CDS markets and rating agencies did not agree on the answer to that question. The updated evidence in this post suggests that there remains a difference of opinion on the effectiveness of the SPOE. It’s possible that investors are still skeptical about the new resolution tool since it has not yet been tested. It’s also possible that bond markets’ perceptions of risk differences between parent and subsidiary banks are concealed by the generally strong financial condition of the four institutions that we consider. Nonetheless, the absence of a market response is notable.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Gara Afonso is a research officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael Blank is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group

How to cite this blog post:

Gara Afonso, Michael Blank, and João A.C. Santos, “Did the Dodd-Frank Act End ‘Too Big to Fail’?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), March 5, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/03/did-the-dodd-frank-act-end-too-big-to-fail.html .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Wilson: Thanks for your comment. While liquidity in the bond market may be an issue (though it is unclear in which way it would bias our results), we obtain a similar conclusion when we rely on CDS spreads. As for the data request, we are not at liberty to share proprietary data, but it can be accessed via subscription to Bloomberg and Markit.

Hi: this is an interesting topic, but the outcome looks different from other work i’ve seen. I wonder if this is affected by the small/ illiquid outstandings of bank level debt. Is your data available? kind regards, wilson

Cornelius: Thank you for reading our post and for your comments. To the extent that there was a “subsidy,” the widening in the rating gap could be a sign of its reduction, consistent with rating agencies’ announcements of a decline in their expectation of government support in the event of financial distress/failure. However, the absence of a similar widening in bond and CDS spreads is not consistent with such a reduction. It would be interesting to extend the analysis to the next tier of institutions, as you suggest, but data availability limits our ability to implement this idea.

Greetings– Thanks for this research. There is much talk of the TBTF “subsidy” enjoyed by several banks and BHCs. The subsidy is a main component of pending legislation addressing the TBTF problem. (H.R. 493) I’d be interested in what the authors (and others) say about whether their analysis helps in determining the existence or the magnitude of the subsidy. Perhaps for contrast an identical study should be conducted for the next tier of non-TBTF banks and BHCs. With appreciation. CKH