The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is arguably the biggest policy intervention in health insurance in the United States since the passage of Medicaid and Medicare in 1965. The Act was signed into law in March 2010, and by 2016 approximately 20 to 24 million additional Americans were covered with health insurance. Such an extension of insurance coverage could affect not only medical bills, but also educational, employment, and broader financial outcomes. In this post, we take an initial look at the relationship between the ACA and higher education financing choices and outcomes. We find evidence that expansions in healthcare coverage may influence both the prevalence of student loans and loan repayment behavior. Specifically, our results suggest that individuals covered by ACA-related expansions are taking out slightly more loans and taking a longer time to start repayment.

Potential Links between ACA and Student Loans

Why might ACA have any relationship to higher education and financial outcomes? Among other things, expanding health insurance could benefit the less wealthy by increasing disposable income (from savings on insurance and healthcare), making it easier for them to repay a loan. Or it could influence the trade-off between training (through higher education) and employment: when to cease education, or when to stop searching for a better employment offer, especially if the Act weakens a link between employment and obtaining health insurance.

Testing for a Relationship

The Act extends health care coverage in multiple ways, including expanding Medicaid eligibility to people whose incomes are up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level (which was $31,720.40 for a family of four in 2014), and enabling children to stay on their parents’ health insurance until they turn twenty-six. With all of the potential ways these expansions in insurance could affect employment and education choices, the correlation of ACA to student loan outcomes is unclear. We examine the relationship quantitatively, using the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (CCP) data provided by Equifax. With this data set, we can observe when individuals in a representative sample of the U.S. population take out a student loan and when they start to repay.

Using the CCP, we compare the outcomes of student loans originated before and after the expansion of Medicaid in states that did expand the program, with those where Medicaid was never expanded; and we also compare loans originated to borrowers just below the twenty-six-year cut‑off with loans to borrowers just above, before and after the introduction of ACA. The Act passes in 2010, but key factors (such as increased eligibility for Medicaid) broadly begin in 2014. We expect any average effect of Medicaid expansion to occur over time (as states expanded at different dates) but not prior to 2010, since the passage of the Act was somewhat surprising. The repayment period of a loan is defined as the beginning of the contractually scheduled repayment period or when actual repayments start, whichever comes first.

ACA and Student Loan Originations

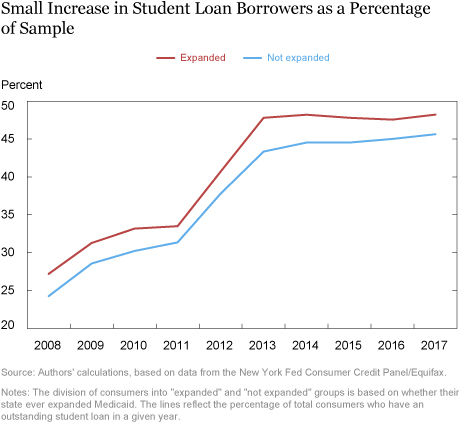

The first outcome we look at reflects a joint decision: whether or not to pursue higher education and to take out a student loan to finance it. The chart below shows the percentage of individuals who have a student loan each year for states that ever expanded Medicaid (between 2010 and 2016) and for states that did not. Note that while the two series were trending upward at similar rates before 2010, after 2010 the origination in expanding states increased relative to that in non‑expanding states. Testing this formally in a differences-in-differences model, we estimate that the gap increased by 2 percentage points after expansion, a finding that is consistent with a small increase in enrollment or a greater use of student loans to finance higher education.

ACA and Student Loan Repayment

Next, we turn to repayment outcomes that are conditional on taking out a student loan. In our sample overall, 45 percent of loans begin repayment one year after origination, and 66 percent begin repayment within two years. A delay in repayment can arise if borrowers remain in school or do not immediately find employment and request a deferral. For our purposes, we focus on repayment of loans within two years as a simple measure of repayment. We choose two years because it represents a “normal” repayment period (two years is approximately the median repayment window in the sample).

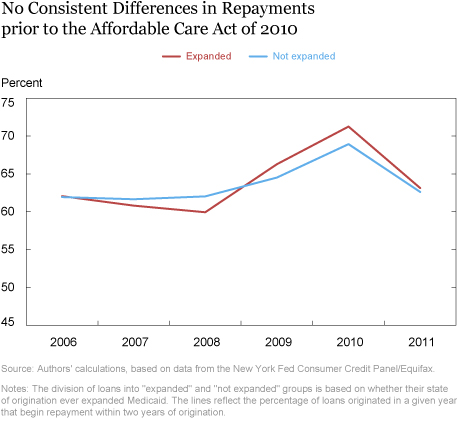

To account for any constant differences between expanding and non‑expanding states and the staggered rollout across states, we move to a differences-in-differences analysis. This considers the difference in student loan outcomes before and after ACA rollout in a state while controlling for overall differences between states that expanded and those that did not. This approach lends itself well to policy evaluation when any differences between “treated” states (those potentially affected by the policy) and untreated states or individuals are constant over time. In the context of ACA’s Medicaid expansion, however, such an assumption could be problematic, as states opt into the expansion. For example, states that opt in could have experienced different economic paths for other reasons, and outcomes could co-vary with expansion because of those different growth paths. To check if expanding states happen to be systematically different, we look at average repayment outcomes by loan origination year for expanding and non-expanding states (see the chart below). We find no large differences in trends prior to 2010. To check for cyclicality, we also look at GDP growth and unemployment rates over a longer time period and find no systematic differences.

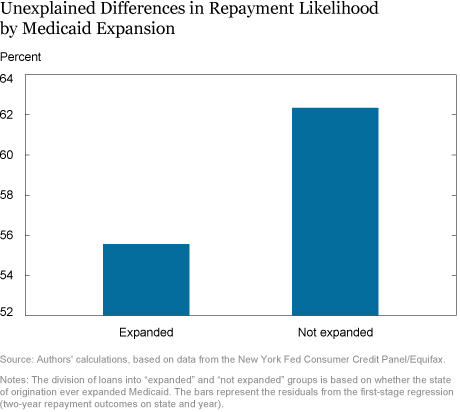

To calculate the difference in student loan repayments associated with the timing of Medicaid expansion, we proceed in two steps. First, we estimate the residual variation in repayment rates not explained by the state and year in which a loan originates. Then, we test if this residual unexplained variation depends on whether a loan originated in an expanding state after its expansion. The bar chart below shows the point estimates from this second regression; the likelihood of repayment within two years was about 4 percentage points lower (56 percent compared with 62 percent) in states and times that expanded Medicaid coverage. In other words, individuals covered by the expansions were less likely to successfully start repaying a loan within two years. This estimated difference is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. As robustness checks in untabulated results, we exclude the early-expansion states (pre-2014) in case they are special in some way, and we observe the same relationship.

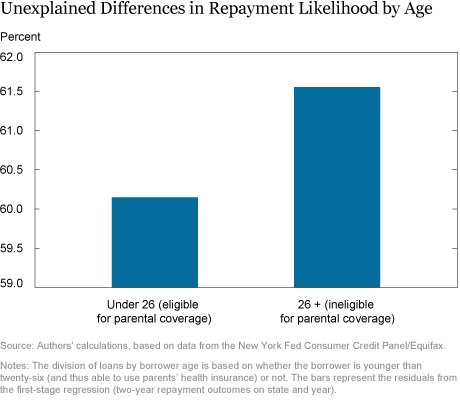

ACA and Age

Next we focus on the effect of the ACA provision that enables children under twenty-six to stay on their parents’ health insurance plan. This analysis may be more interpretable as causal because the whole cohort is affected by the provision. Proceeding as above, we estimate that after ACA, individuals just below the age cutoff (twenty-four to twenty-six) are 1 percent less likely to have begun repayment within two years compared with those above the cutoff (twenty-seven to twenty-eight). This estimated difference is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. The relationship with parental coverage is similar to the one above, albeit substantially smaller in magnitude.

Understanding the Findings

In this post, we’ve provided the first examination of how insurance expansions under ACA correlate with student loan outcomes. We find that expansions in healthcare coverage are associated with a greater likelihood of taking out a student loan, and that fewer borrowers begin repayment of these loans within short (two-year) time horizons. The reasons for this are not clear yet, but possibly include composition effects (different choices in type of education pursued); borrowers financing more, or more expensive, education; or borrowers pursuing education for longer and thus forestalling repayments. In future research, we will examine new data sets with additional educational outcomes (merged to the CCP) in order to better disentangle the mechanisms behind these findings.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Maya Bidanda is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sean Hundtofte is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim L. Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Maya Bidanda, Rajashri Chakrabarti, Sean Hundtofte, and Maxim L. Pinkovskiy, “Do Expansions in Health Insurance Affect Student Loan Outcomes?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), March 28, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/03/do-expansions-in-health-insurance-affect-student-loan-outcomes.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics