The European Central Bank (ECB)’s marginal lending facility has been used by banks to borrow funds both in normal times and during the crisis that started in 2007. In this post, we argue that how a central bank communicates the purpose of a facility is important in determining how users of the facility are perceived. In particular, the ECB never refers to the marginal lending facility as a back-up source of funds. The ECB’s neutral approach may be a key factor in explaining why financial institutions are less reluctant to use the marginal lending facility than the Fed’s discount window.

What Is the Facility’s Original Purpose and Intent?

The marginal lending facility was established in 1998 when the ECB was founded. The facility provides overnight loans to financial institutions, and serves as a complement to open market refinancing operations, which are the ECB’s main means of providing liquidity. From the beginning, the marginal lending facility was assigned an explicit monetary policy role, with its rate serving as the ceiling of the “interest rate corridor” in the ECB’s monetary policy framework. As a monetary policy tool, the marginal lending facility shares the same counterparty and collateral policies as the ECB’s open market refinancing operations.

The ECB intends for the marginal lending facility to be used freely and in tandem with its main refinancing operations, which offer funds for a seven-day term and at a lower interest rate than the marginal lending facility. Despite the higher rate, banks sometimes prefer to borrow from the marginal lending facility; if a bank doesn’t need funds for a full week, it may be more advantageous to borrow on an overnight basis from the marginal lending facility. The overnight facility is open throughout the day and closes at 6:30 p.m., thirty minutes after the close of the payments system. Borrowing at the marginal lending facility is automatically triggered when a bank’s account at the ECB ends the day with a negative balance, provided that the bank has sufficient collateral at the central bank to secure the loan.

Is There Stigma with the Facility?

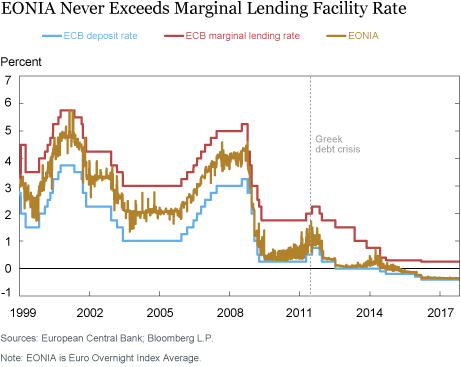

Are banks hesitant to borrow from the marginal lending facility because of a perceived stigma, whereby borrowing is viewed by market participants as a signal of a bank’s financial weakness? One widely used indicator of stigma is the relationship between the overnight interbank rate and the standing facility rate. If the overnight rate rises above the standing facility rate, that is usually interpreted as a sign that stigma may exist with the standing facility. The assumption is that if the bank has sufficient collateral with the central bank to secure the borrowings, it should not prefer to pay a higher rate in the market, all else equal. If the bank still chooses to borrow in the market at a higher rate, it likely means that negative consequences are associated with use of the standing facility.

In the euro area, the overnight interbank rate, as indicated by the Euro Overnight Index Average (EONIA), has never exceeded the marginal lending rate since the ECB was established, despite numerous episodes of sustained stresses in the funding markets (see chart below). Banks’ free access to liquidity through the ECB’s refinancing operations has likely been an important factor for the EONIA remaining within the corridor, but another potential explanation is that banks have not been reluctant to use the marginal lending facility when it is economical to do so, suggesting an absence of stigma in the facility.

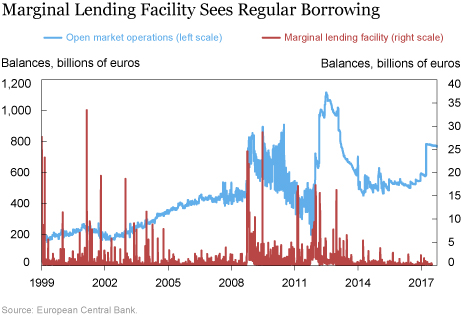

Another possible indicator of stigma with the standing facility is its level of usage. Borrowing has been consistent under the marginal lending facility since its inception, as shown in the chart below. While such borrowing has decreased in recent years, this decline does not necessarily indicate stigma, as the level of usage depends on a variety of factors including market conditions and the amount of liquidity provided by other monetary policy tools. At the ECB, banks can obtain as much liquidity as needed from the weekly refinancing operations, which have been under a full allotment format since 2008. Therefore, banks no longer need to use the marginal lending facility as much as they did before.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that banks may rely on the marginal lending facility when there is upward pressure on market rates. In a phenomenon known as “reverse stigma,” a few of the largest banks have been known to favor borrowing at the ECB’s main refinancing operations over borrowing in the interbank market at an above-market rate. They are concerned that paying up even slightly may weaken their future bargaining power, and they prefer to borrow anonymously from the ECB at an even higher rate. Although reverse stigma is not a widespread phenomenon at the ECB, its existence highlights the extent to which banks are comfortable in using the ECB’s facilities, including the marginal lending facility.

Why Didn’t the ECB’s Marginal Lending Facility Develop Stigma?

The ECB’s experience with stigma stands in contrast to the U.S. experience, where the overnight interbank rate, as represented by the federal funds rate, has occasionally overshot the primary credit rate owing to stigma. In particular, in the lead-up to the financial crisis of 2007-08, the federal funds rate often traded above the primary credit rate, a development that was primarily attributed to stigma.

One explanation for these divergent experiences might be the respective disclosure policies on standing facility borrowings. While the ECB provides a daily disclosure of borrowings under the marginal lending facility, it does so only at an aggregate level. The ECB does not show borrowings of individual banks, or other components of aggregate borrowings, even on an ex post basis. This approach helps mitigate banks’ concerns that their borrowings will become known by other market participants. The Federal Reserve is more transparent in that it provides a breakdown of the borrowings by district in its weekly disclosure, in some cases potentially enabling market participants to deduce who the large borrowers are based on their districts. In addition, under the provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, the Fed is required to provide detailed information, on a two-year lag, about its loans to depository institutions. The Bank of England’s disclosure policy, meanwhile, is not unlike the ECB’s policy, and yet its facility did become stigmatized during the last crisis. This disparity in outcomes suggests that differences in disclosure policy may not fully account for why stigma varies across central bank jurisdictions.

Another explanation for the central banks’ divergent experiences might be the use of automatic loans at the ECB, which is in contrast to the Fed’s practice of requiring all loans to be initiated by banks. The Fed’s approach gives banks leeway not to borrow if they have concerns about stigma. However, this difference may only partly explain the lack of stigma at the ECB, because if a bank wishes to borrow from the ECB earlier in the day before its account balance turns negative, it must initiate a loan request in the same way as at the Fed.

Still another reason might be differences in counterparty and collateral frameworks. At the ECB, the counterparty and collateral policies are identical for open market operations and the marginal lending facility. This approach allows banks to borrow on similar terms at the lending facility and the refinancing operations, which reinforces the “routine” nature of the borrowings at the overnight facility. In contrast, at the Fed, banks may borrow from the discount window but are generally not eligible to participate in open market operations, and a wider set of collateral is accepted at the discount window than in open market operations. This disparity could lead to the perception that the Fed’s discount window attracts weaker banks. However, harmonized counterparty and collateral policies alone may not be sufficient in preventing stigma, as such policies did not preclude the Bank of England’s standing lending facility from developing stigma during the last crisis.

Finally, an important point that is often overlooked is how the central bank characterizes the purpose of the standing facility, because this helps determine how the facility’s use is viewed by market participants. The ECB never refers to the marginal lending facility as a back-up source of funds, but rather as an overnight facility that banks can make free use of. The ECB’s approach is in contrast to that of the Fed, which in recent decades has consistently referred to its discount window as a back-up source of funds, even after it was reformed in 2003 and the primary credit facility was established. The Fed’s approach may have given market participants the impression that the discount window should generally not be used. While its characterization is more understated, the Bank of England has also indicated in its Red Book that its operational standing facility is intended to be used as a back-up source of funds to help manage “unexpected payment shocks.” The ECB’s relatively neutral communication stance may have gone a long way in preventing stigma from developing in the marginal lending facility.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Helene Lee is a senior associate in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Helene Lee is a senior associate in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Helene Lee and Asani Sarkar, “Is Stigma Attached to the European Central Bank’s Marginal Lending Facility?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), April 16, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/04/is-stigma-attached-to-the-european-central-banks-marginal-lending-facility.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

A borrowing from the discount window has always been perceived to be the bank’s mistake. A borrowing from the marginal lending facility (particularly before the full-allotment period) has always been perceived to be the ECB’s mistake – the ECB had underprovided reserves to meet their rate targets because they had mis-estimated some subset of the factors effecting reserve balances.