Almost half the U.S. merchandise trade deficit was tied to petroleum ten years ago. Oil prices were above $100 a barrel, the economy was doing well enough that oil consumption was growing despite high oil prices, and domestic oil production was falling. The U.S. petroleum trade balance has since narrowed substantially from $400 billion in 2008 to under $65 billion in 2017 as a result of lower oil prices, higher domestic production, and a prolonged period of flat-to-falling petroleum consumption. Going forward, the changes in domestic production and consumption have significantly moderated the impact of oil prices on the petroleum trade deficit. That is, changes in oil prices are increasingly redirecting income between domestic consumers and producers rather than between U.S. consumers and foreign oil producers.

The Surge in Oil Production and the Stall in Consumption

The domestic supply and demand conditions for petroleum have significantly changed in the last decade. It was not too long ago that a trend decline in U.S. oil production was accepted wisdom. Industrial production data on crude oil extraction show around a 10 percent drop over the course of the 1980s and a 20 percent drop in the 1990s. The trend decrease ended in 2006, and after a few years of stability, production started to increase in 2009 and then took off in 2012. A sharp drop in oil prices in late 2014 caused production to falter, but then, somewhat unexpectedly, domestic production fully recovered in short order, despite no rebound in oil prices.

The trend growth in consumption changed a bit earlier than the change in U.S. production. According to personal consumption expenditure data, the volume of gasoline purchased rose 8 percent in the 1980s and 17 percent in the 1990s. Purchases then stalled before falling in 2008 with the economic downturn. Gasoline sales continued to fall until the drop in oil prices helped push sales up in 2015 and 2016, only for the downward trend to reassert itself in 2017.

A steady run-up in oil prices helps explain the weak consumption data since 2000. Prices rose from around $30 a barrel in 2000 to $55 a barrel in 2005 and $100 a barrel in 2008. There was a drop in prices with the global financial crisis, but prices reverted to about $100 a barrel by 2011. The rise in oil prices and improvement in fuel efficiency contributed to the volume of gasoline purchases being down 6 percent since 2000, even as overall consumer spending increased by around 50 percent over this period.

Taking Market Share from Foreign Oil Producers

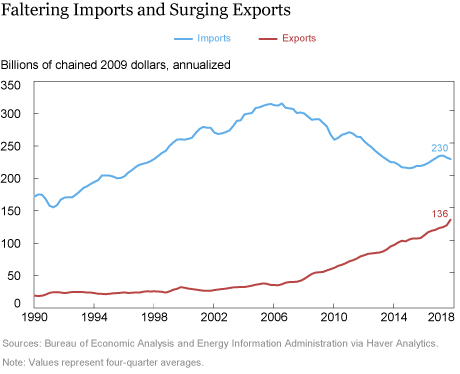

These reversals in the trend behavior of domestic consumption and production are reflected in the volume of U.S. imports and exports of petroleum products. The chart below has imports and exports from the national accounts, in chained 2009 dollars, so the data reflect the volume of petroleum products going in and out of the United States. Oil imports increased 55 percent in the 1990s and another 16 percent from 2000 to 2005, a near doubling over just fifteen years. The surge in domestic oil production and stalled consumption then reversed this trend with oil imports in 2017 down 27 percent from 2005 levels. This decline in imports would have likely been bigger if not for the drop in U.S. production following the 2014 collapse in oil prices. Note that imports fell again in 2017 once U.S. production recovered.

The implications of the changed supply and demand conditions in the U.S. oil market are also evident on the export side. U.S. producers have found it increasingly expedient to enter foreign markets and move beyond selling to the domestic market. Export volumes are up almost 300 percent since 2005, albeit from a small base. Last year, shipments rose 12 percent, with the increase reflecting a push into China and the rest of Asia as U.S. producers took market share from Saudi Arabia which has cut back production in an effort to support oil prices.

Declining Impact of Oil Prices on U.S. Income

The lower volume of petroleum imports and the surge in petroleum exports reduces the impact on the U.S. economy, as a whole, when oil prices change. Consider the extreme of the United States importing all of its petroleum. A rise in oil prices can be viewed as analogous to a tax without a deadweight loss on U.S. consumers and firms, with the revenue flowing out to foreign producers. This measure of “after-tax” domestic income would then fluctuate with oil prices. At the other extreme, if the United States produced all the oil it consumed, then the “tax” revenue would flow from firms and consumers to domestic petroleum producers.

The “after-tax” considerations of oil prices have diminished considerably. For example, the petroleum trade deficit equaled $62 billion in 2017 when oil prices were near $50 a barrel. The last year with similar oil prices was 2005 when the deficit came in at $230 billion. That is, around $170 billion less in income now flows out of the country at this oil-price level because of changes in domestic production and consumption since 2005.

Alternatively, consider another exercise that measures how much less revenue would flow out if oil prices were back to $100 a barrel. Namely, apply the 2008 price deflators for petroleum imports and exports to the volume data in the chart above. The resulting counterfactual calculation is that the 2017 petroleum trade deficit would have been $165 billion if oil prices were at $100 a barrel, a much smaller sum than the 2008 deficit of near $400 billion. The implication is that, if prices had been $50 a barrel higher in 2017, then the petroleum deficit would have been only $100 billion wider, assuming no change in trade volumes. Note that such a jump in prices would likely reduce consumption and boost domestic oil production, pointing to an even more modest deterioration in the deficit.

This is not to say that a jump in oil prices will be painless for consumers and firms. The impact, though, is muted as much more of the “tax” is flowing to the domestic petroleum industry and less is being sent out of the country than was the case just a decade ago.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Michael Fosco is former senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Michael Fosco and Thomas Klitgaard, “Recycling Oil Revenue,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), May 14, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/05/recycling-oil-revenue.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

US Oil Refiners prefer and are set up for Heavier Oil vs light oil. The US Refineries are more geared to heavier oil. The US producers for light oil find export MKTS especially in Europe. One of the main reasons for increase in Oil exports. The current production from fracking is a short term boast these wells have a short time frame and production drop off is quick, in many cases a 63% drop off after the first year. Oil Price – you should consider in your future calculations that the price of Oil will drop and revisit its lows of the mid $20 range and should break below the lows and set new lows. Something else to consider, several of the Oil companies that are producing from fracking have heavy Debt Loads and going forward and will not be able to service their Debt. We shall see Debt Deflation.