Import tariffs are on the rise in the United States, with a long list of new tariffs imposed in the last few months—25 percent on steel imports, 10 percent on aluminum, and 25 percent on $50 billion of goods from China—and possibly more to come. One of the objectives of these new tariffs is to reduce the U.S. trade deficit, which stood at $568.4 billion in 2017 (2.9 percent of GDP). The fact that the United States imports far more than it exports is viewed by some as unfair, so the idea is to try to reduce the amount that the nation imports from the rest of the world. While more costly imports are likely to reduce the quantity and value of imports into the United States, the story does not stop there, because we cannot presume that the value of exports will remain unchanged. In this post, we argue that U.S. exports will also fall, not only because of other countries’ retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports, but also because the costs for U.S. firms producing goods for export will rise and make U.S. exports less competitive on the world market. The end result is likely to be lower imports and lower exports, with little or no improvement in the trade deficit.

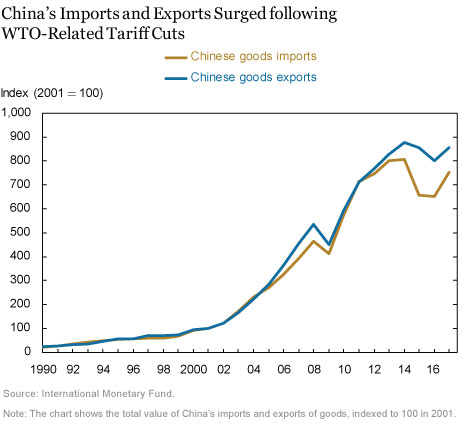

One way to see that higher import tariffs will reduce exports is to look at the experience of countries that have changed their import tariff rates. China reduced its import tariffs when it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001. Although China had lowered its tariffs prior to that time, in 2000 they were still fairly high, averaging 15 percent. By 2006, this average tariff rate had fallen by 40 percent, to 9 percent. We can see from the chart below that the growth rates of both China’s exports and its imports increased enormously (more than 25 percent on average per year) following its WTO accession, with both growth rates more than doubling in the five years after China joined the WTO, compared with the five years prior to joining.

Of course, we cannot tell from this chart what caused the increase in exports. Many reforms were taking place in China at that time in addition to trade liberalization. In order to identify the effect of lower import tariffs on China’s exports, recent research has turned to using highly disaggregated Chinese firm-level data with information on all the products a firm imports and exports. The research shows that between 2000 and 2006 (the period for which detailed firm-level data are available), China’s imports increased and so did its exports.

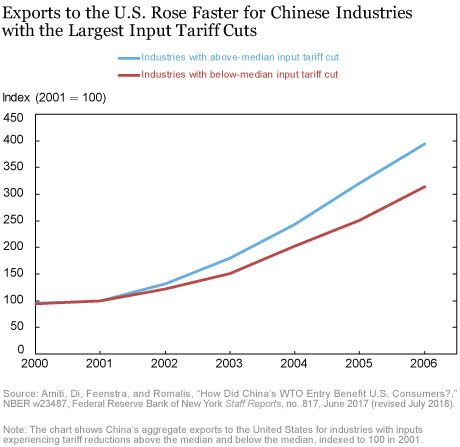

Focusing on China’s exports to the United States, our research paper (“How Did China’s WTO Entry Affect U.S. Prices?”) shows that by lowering its own tariffs on imported inputs, China reduced its production costs and increased productivity, enabling Chinese firms to enter the U.S. export market and compete with other firms. With a fall in production costs, Chinese firms charged lower prices on goods exported to the United States and increased their U.S. market shares. A large part of the market-share gains stemmed from new varieties of goods exported by Chinese firms entering the U.S. export market.

The link between lower input tariffs and stronger export growth can be seen in the chart below. Chinese firm-level exports to the U.S. are aggregated into two groups: the group of Chinese industries that experienced large tariff cuts on imported inputs (specifically, average tariff cuts above the median, equal to 4.6 percentage points or 43 percent), and the group of industries that experienced input tariff cuts below the median, with both indexed to 100 in 2001. We can clearly see that Chinese exports to the United States grew much more rapidly in industries that experienced the largest drops in input tariffs.

The evidence from China’s experience strongly suggests that a country that increases its tariffs is likely to not only reduce its imports but also reduce its exports. Many large exporters are also large importers that depend on imported inputs for production of their exports. Even if U.S. exporters switch to domestically produced inputs their costs will still rise, because competing domestic suppliers will be able to increase their markups in the industries that are protected by higher tariffs. For example, with a 25 percent steel tariff, domestic steel producers can increase their markups and still stay competitive. It is the U.S. exporters that rely on these inputs that will be adversely affected. And this is even before we take into account the cost to exporters from the retaliation by other countries.

While we cannot predict the size of the trade deficit, what seems clear from our analysis is that import tariffs will reduce both imports and exports.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Mary Amiti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Mi Dai is an associate professor at Beijing Normal University.

Robert C. Feenstra is a professor at the University of California, Davis.

John Romalis is a professor at the University of Sydney.

How to cite this blog post:

Mary Amiti, Mi Dai, Robert C. Feenstra, and John Romalis, “Do Import Tariffs Help Reduce Trade Deficits?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 13, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/08/do-import-tariffs-help-reduce-trade-deficits.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks for replying. I am not convinced one should conclude that ‘what seems clear from our analysis is that import tariffs will reduce both imports and exports’, when, in your study, even the industries with below-median input tariff cut experienced 200% growth in exports (vs. 300% for above-median), suggesting that revenue boost from weak CNY was a bigger force than cost reduction from input tariff cut.

Bob: Thank you for your comment. We agree with your statement that “A prohibitive tariff will stop ALL trade and cause a zero trade balance.” However, even if we know the trade balance at the end points, it doesn’t mean we can predict how it will evolve if we were to raise tariffs from where we stand now to some non-prohibitive level. As we point out in the concluding statement in the blog post, “While we cannot predict the size of the trade deficit, what seems clear from our analysis is that higher import tariffs will reduce both imports and exports.”

Rajat: Thank you for your comment. As you point out, exchange rate movements can affect exports. However, this was not the focus of our analysis. Instead, we were trying to identify how changes in import tariffs on intermediate inputs in China would affect China’s exports to the U.S. We do this by looking at differential effects—essentially comparing Chinese exporters to the U.S. that imported inputs subject to a big drop in import tariffs with those that experienced a small change in import tariffs for their inputs. All of the Chinese exporters were exposed to the same exchange rate changes but they differed in their exposure to input tariff liberalization. The Chinese firms in industries that experienced the largest fall in input tariffs were the ones that experienced the relatively largest boost in exports to the U.S.

A small tariff may not reduce the trade deficit, but a prohibitive one surely will. A prohibitive tariff will stop ALL trade and cause a zero trade balance. So, at some point a general tariff has gotta work. But that does not mean it’s a good idea.

In that period, USD depreciated against other DM currencies, while CNY was pegged (to USD) throughout that period. Does this artificial ‘export incentive’ help China to emerge as the major exporter to the globe?

Thank you for the insightful analysis! Sincerely