The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), created in 2011, is a key element of post-crisis U.S. financial regulation, as well as the subject of intense debate. While some have praised the agency, citing the benefits of consumer financial protection, others argue that its activities involve high compliance costs, increase uncertainty and legal risk, and ultimately reduce the availability of financial services for consumers. We present new evidence on whether the CFPB’s supervisory and enforcement activities have significantly affected the supply of mortgage credit, or had other effects on bank risk-taking and profitability.

CFPB Supervision and Enforcement

The CFPB, established as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, opened its doors in July 2011 with a consumer financial protection mandate and with broad authority over both banks and nonbanks. In addition to rule-making authority, the CFPB has the power to supervise and conduct examinations of financial firms and pursue enforcement actions for breaches of federal consumer financial protection law. Since its founding, the CFPB has actively exercised its supervisory and enforcement authority—conducting examinations on a wide range of topics, undertaking more than 200 public enforcement actions, and recovering more than $12 billion in relief to consumers.

Supporters argue that robust supervision and enforcement are critical for ensuring compliance with consumer financial protection laws. Critics have argued that the CFPB’s approach amounts to “regulation by enforcement,” creating legal uncertainty among firms and reducing the availability of financial services. They also argue that CFPB supervision is burdensome and diverts firms’ resources, particularly for smaller financial institutions.

Measuring the Effects of CFPB Oversight

In a recent research paper, we aim to measure the effects on banks of CFPB supervision and enforcement activities, which we refer to as CFPB “oversight.” We make use of the fact that small depository institutions with $10 billion or less in total assets are generally exempt from direct CFPB examinations and enforcement actions. Instead, compliance with consumer financial protection laws is primarily overseen by the firms’ prudential supervisor (for example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in the case of national banks and national savings associations). Unlike the CFPB, these prudential supervisors generally focus on overall issues of safety and soundness rather than consumer financial protection alone.

We examine outcomes before and after July 2011, when the CFPB begins operations, and compare commercial banks and savings banks on either side of the $10 billion asset threshold for CFPB oversight. (Our empirical approach takes into account the fact that some firms with $10 billion or less in assets are still subject to CFPB oversight, in particular small banks that have larger affiliates.)

There are other regulatory implications for banks crossing the $10 billion mark, related to caps on debit interchange fees and the requirement to conduct company-run stress tests. To isolate the effects of the CFPB, we focus on consumer lending outcomes, and exploit differences in the timing of the creation of the CFPB relative to the implementation of stress tests. But to the extent that we can’t fully disentangle the effects of these different regulations, our estimates should be interpreted as an upper bound on the effect of CFPB oversight.

Our empirical strategy does not shed light on the effects of new regulations issued by the CFPB under its rule-writing authority, such as the “know before you owe” rule. That is because these rules generally apply to all banks, even those that are exempt from direct CFPB supervision and enforcement. We also note that our results don’t represent an overall assessment of the welfare effects of the CFPB—in part because we cannot easily measure the possible benefits of enhanced consumer protection.

Effects on Total Mortgage Lending—Much Ado about Nothing?

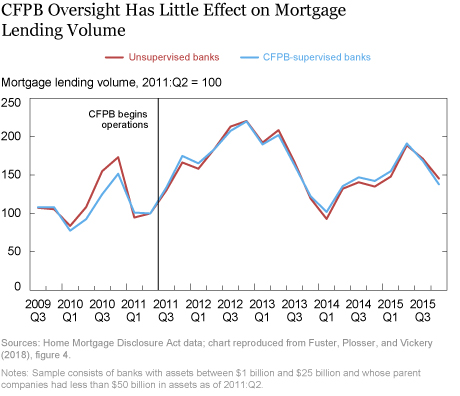

Does CFPB oversight reduce overall lending? We take commercial banks and savings banks with total assets between $1 billion and $25 billion as of June 30, 2011, and sort them into two groups: those that became subject to CFPB oversight when the Bureau started operating in mid-2011 and those that did not. The figure below plots mortgage lending volumes for these two groups, using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data.

The volume of mortgage lending for both groups fluctuates substantially over time, reflecting movements in long-term interest rates and other factors. However, there are no obvious differential trends—lending volumes move very closely together for the two groups. In other words, there is no evidence that being subject to CFPB supervision and enforcement has led to lower mortgage lending for affected banks.

In our research paper, we also estimate the lending effects of CFPB oversight using a loan-level statistical model that accounts for the location of the mortgaged property and other loan characteristics. The results of this more detailed analysis back up the story shown in the chart above. The estimated effect of CFPB oversight on mortgage origination volume is economically small and generally not statistically different from zero. We also find that banks subject to CFPB oversight are no more likely to reject mortgage applications than other banks.

Our empirical estimates also allow us to put a statistical “upper bound” on the average effect of being subject to CFPB supervision and enforcement on mortgage lending. We find that CFPB oversight reduces affected lenders’ share of mortgage originations by at most 1.6 percentage points, a small decline relative to the overall 38 percent market share of these lenders in our sample.

Effects on the Composition of Mortgage Lending

Although CFPB oversight has not led to an overall decline in mortgage lending, we do find effects with respect to the composition of lending. Most notably, we find a 6 percent drop in the market share of CFPB-supervised banks for mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). These loans tend to be riskier since they are made to lower-income borrowers and generally involve a small down payment. There is also some evidence of a drop in lending to borrowers with higher credit risk. Offsetting these declines, CFPB-supervised banks substitute toward large loans in the “jumbo” segment of the mortgage market, where borrowers tend to have higher incomes.

These results are notable in light of the fact that many lenders, particularly banks, have exited FHA lending in recent years, sometimes citing legal and regulatory risks associated with this segment of the mortgage market. Our results are consistent with the view that these risks have indeed contributed to lower FHA lending and risky mortgage lending in general.

Other Effects

We also investigate the effects of being subject to CFPB supervision and enforcement activities on a number of bank-level outcomes, including asset growth and noninterest expenses. We don’t find any evidence that banks just below $10 billion in size grow more slowly to avoid crossing that regulatory threshold. If anything, these banks grow slightly faster on average. (As a robustness check, we also confirm that our results on mortgage lending look similar even when we exclude banks with assets very close to $10 billion from our analysis.) We don’t find any effects of CFPB bank oversight on noninterest expenses, although our statistical approach is unlikely to detect moderate increases in overheads due to regulatory compliance costs.

Implications for Policy

Our results provide some support for the view that heightened supervisory scrutiny related to consumer financial protection has led to some “de-risking” of bank activities and, in particular, has affected bank lending to FHA borrowers. However, claims that CFPB supervision and enforcement activities have induced a collapse in consumer lending do not seem to be correct, at least for mortgage lending and for the set of banks studied in our paper.

Our results may be of use to policymakers, particularly in light of efforts to raise the asset size threshold for CFPB oversight, which would exempt more depository institutions from the Bureau’s supervision. However, our results do not speak directly to the overall net welfare costs and benefits of the CFPB’s activities, given that we analyze only a small subset of their effects.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Andreas Fuster is an economic advisor in the financial stability department at the Swiss National Bank.

Matthew Plosser is a senior financial economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Vickery is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Vickery is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Andreas Fuster, Matthew Plosser, and James Vickery, “Analyzing the Effects of CFPB Oversight,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 9, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/10/analyzing-the-effects-of-cfpb-oversight.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I don’t expect a truthful or objective review of one Federal Governmental Entity by another. Whether the consumer actually benefited from $12b in relief or not seems a spurious claim, and one that was probably provided by the CFPB itself in justification for its existence. The article does not address the fact that the CFPB’s actual existence is outside the purview of any Governmental Oversight including Congress. It’s not surprising as the Federal Reserve was extra-legal when established and it took the 16th Amendment to make it legal.